8. Values-Based Management and the Burra Charter: 1979, 1999, 2013

- Richard Mackay

Values-based heritage management provides a basis for good decision making for cultural heritage places. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance (), offers a framework in which multiple, sometimes conflicting heritage values and other values and relevant issues can be understood and explicitly addressed. This approach makes it possible to discern relative priorities (such as an overarching objective to retain important attributes) while responding to applicable site constraints, resource limitations, or statutory requirements. One of the key factors in the success of the charter, which has been widely used in Australia and internationally, is that its core values-based premise has proven to be extremely flexible and applicable to a broad range of places and changing circumstances.

The Australian charter has its antecedents in the Charter of Athens, which was adopted at the First International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments in 1931 (). The Charter of Athens incorporated seminal concepts, including the need for expertise and critique, the appropriateness of modern materials, importance of the setting, and statutory protection, but it had a strong focus on architecture, archaeology, and the fabric of historic monuments. These principles were incorporated in the International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (the Venice Charter) () prepared at the Second International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Venice, 1964, which was subsequently adopted by the then-fledgling International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in 1965. Itself an artifact of its time, the Venice Charter is strongly focused on archaeological site conservation and the restoration of architectural monuments. Emanating from a Eurocentric base, it was never conceived to apply to more ephemeral “New World” places with nonstructural physical evidence or intangible values. It was for this reason that during the early years of Australia ICOMOS, energies were focused on the development of a new bespoke doctrinal document for conservation practice—one that reflected the nature, multifaceted values, and circumstances of Australian cultural heritage places. The result was the Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance, adopted at Burra Town Hall in South Australia in 1979, which soon became known as the Burra Charter ().

The Burra Charter is a dynamic document that has evolved to reflect changes to professional practice and emerging issues. The challenges confronted by cultural heritage conservation practitioners and decision makers also change over time and have increasingly included broader societal considerations. Amendments to the original 1979 Burra Charter in 1999 and 2013 have responded accordingly by developing methodologies that engage with emergent issues, such as growing awareness of intangible attributes and the legitimate expectations of associated communities, to become more engaged in decision making for heritage, which is recognized and valued as a public asset. The fundamental values-based principles and logical sequence of processes of the Burra Charter, and its format and presentation, have not altered (), but are flexible and readily accommodate evolving notions of heritage and changing economic or political circumstances, as well as vastly different types of place. The resulting conservation policies and heritage management models have moved away from traditional fabric-centered approaches, which emerged in Europe during the mid-twentieth century, toward more holistic and innovative conservation solutions. The most impactful changes to the Burra Charter occurred in 1999 and included explicit recognition of nonphysical values such as “use, association and meaning,” cultural diversity and the potential for divergent or conflicting values, and the legitimate rights and expectations of people who are associated with a place (). This broader, more inclusive view of both values and people is apparent from the outset, in Article 1.2 of the 1999 charter:

Cultural significance means aesthetic, historic, scientific, social or spiritual value for past, present or future generations. Cultural significance is embodied in the place itself, its fabric, setting, use, associations, meanings, records, related places and related objects. Places may have a range of values for different individuals or groups. ()

The changes made to the Burra Charter in 2013 were directed primarily at standards of practice and also include development of a range of associated Practice Notes, which provide specific guidance on the application of the Burra Charter to matters ranging from Indigenous cultural heritage to new work at a heritage place or place interpretation (). These guidelines, some of which are now in effect, with others still being prepared by Australia ICOMOS, provide evidence of the multiple types of place and variety of projects to which the Burra Charter may apply.

The charter is not without critics; some for instance suggest that there is an overreliance on intrinsic values of places (), while others express skepticism regarding the respective roles and relative power of experts, as opposed to associated communities, basing such conclusions on the framework provided by Laurajane Smith’s concept of authorized heritage discourse (; ; ). Others still question whether the Burra Charter’s values-based approach deals adequately with living cultures (). While these are relevant and valid questions, such critiques typically originate from academic perspectives and are not always grounded in real experience or the actual local cultural context of the charter at work. There are instructive examples of the charter used effectively, in different cultural and community contexts, to assess, conserve, and manage a broad range of places with both tangible and intangible attributes, including as part of the Living with Heritage, Heritage Management Framework, and Tourism Management Plan projects at Angkor, Cambodia (; ). An important consequence of the growth in understanding of the knowledge, roles, and rights of associated people is the shift in professional practice from “expert” to “facilitator” (, 636).

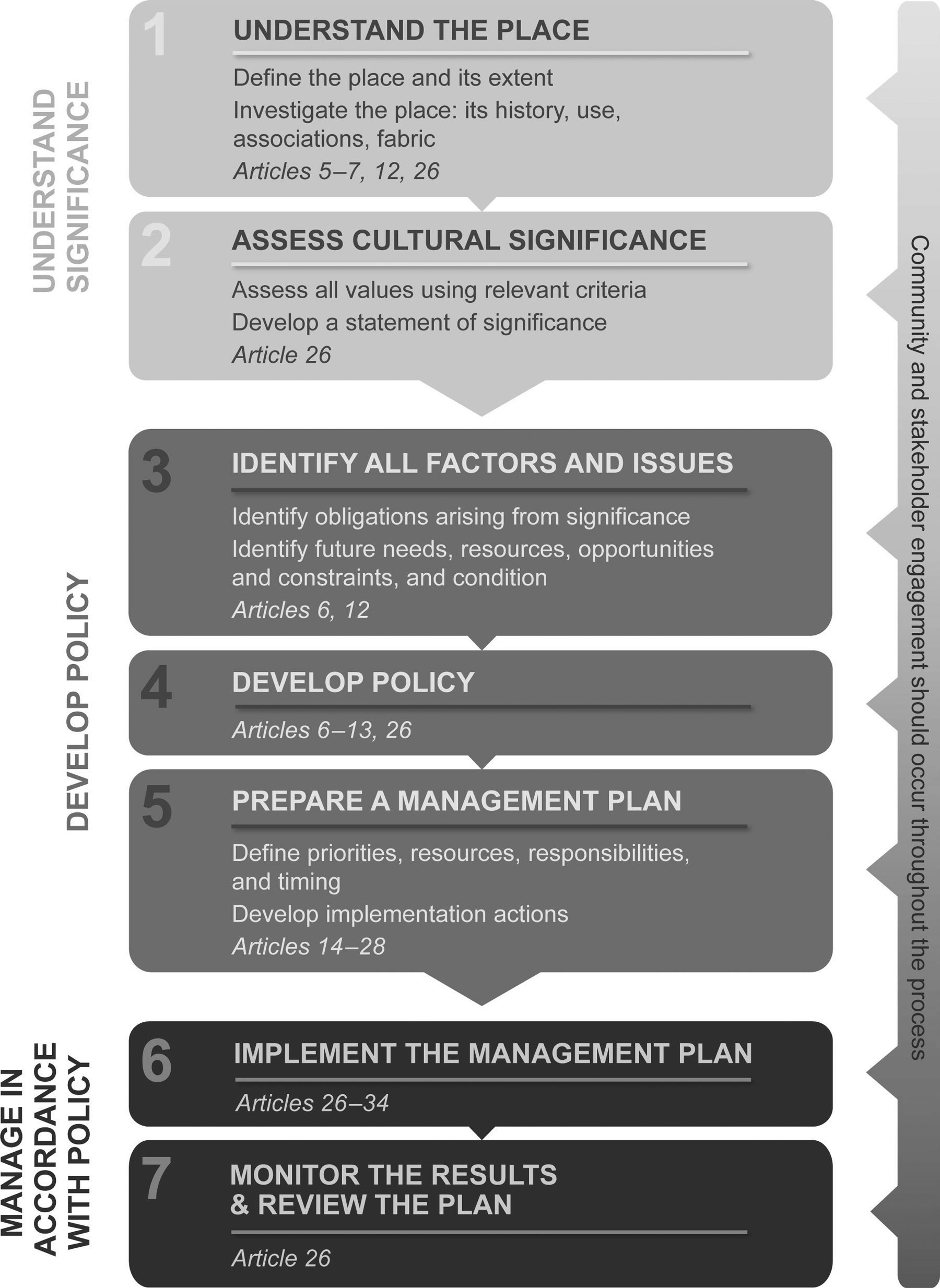

The values-based approach of the Burra Charter is encapsulated in a simple and logical process, which is:

- Understand significance (understand the place and assess cultural significance);

- Determine policy (identify all factors and issues, develop policy, prepare a management plan);

- Manage in accordance with policy (implement the management plan, monitor the results, and review the plan).

This process is summarized in the simple steps shown in (fig. 8.1), which has been reproduced from the current (2013) version of the charter. The adaptability of the charter’s approach to suit varied types of value and different circumstances is discussed below in relation to three very different places and projects, all in Sydney.

Figure 8.1

Figure 8.1Luna Park: Just for Fun

Luna Park is a 1930s-era amusement park located beside the northern end of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, on the harbor shoreline. It is listed in the New South Wales State Heritage Register, and several of its buildings and structures are also listed as heritage items at the local level ().

The location of Luna Park has a layered history that commences with pre-European occupation of the harbor foreshore by Cadigal people of the Eora Nation, although no physical evidence from their presence remains. The postcolonial history of the site is closely bound to the development of the nearby city of Sydney and its North Shore. The wharf for the first regular ferry service across the harbor was here, and in the late nineteenth century the precinct become a major transport interchange for ferries, trains, and trams. In the 1920s the site held erecting shops (engineering workshops) and staging wharves for the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, where steel components were assembled before being ferried onto the harbor and lifted into place.

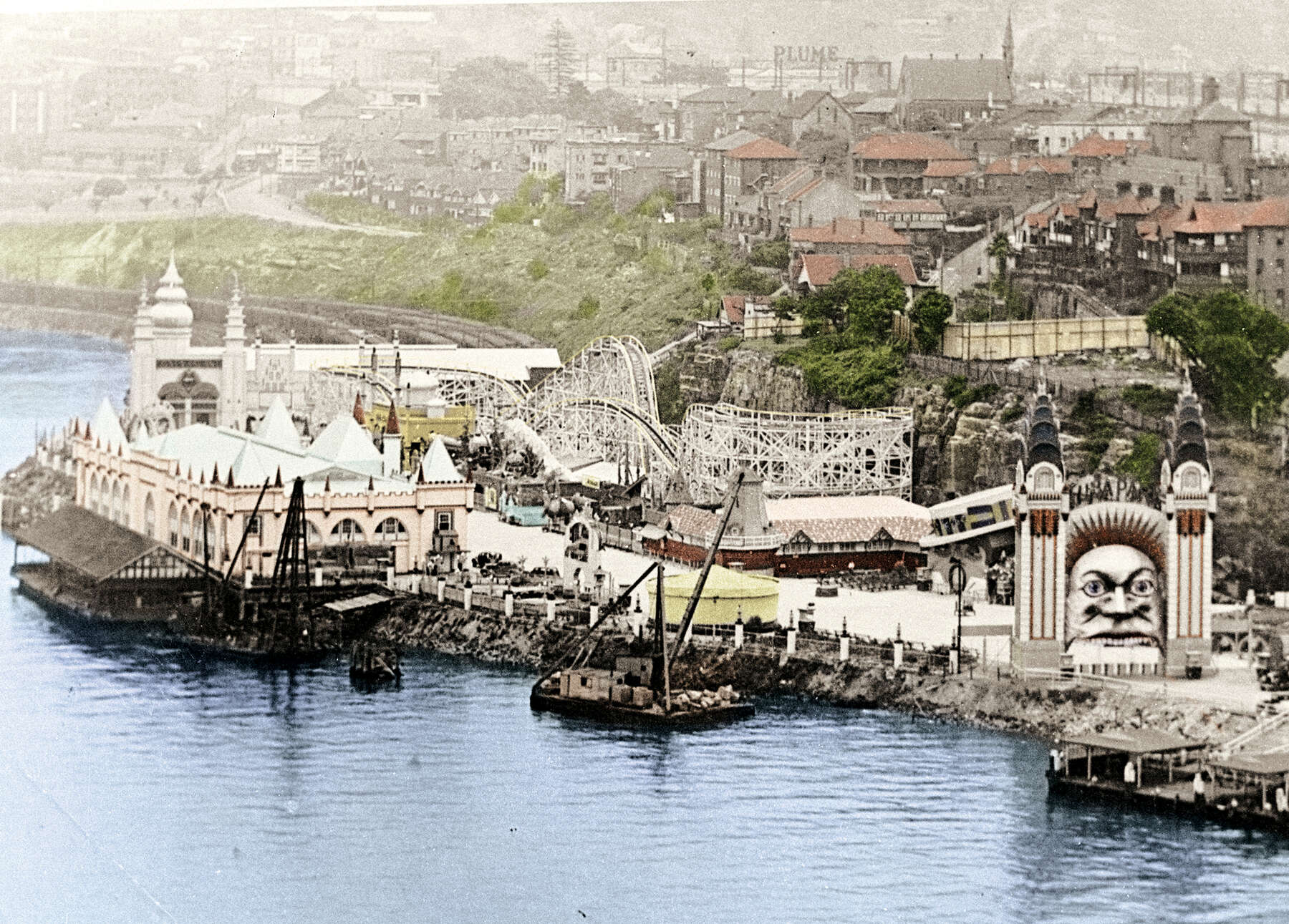

Once the Sydney Harbour Bridge was completed and opened in 1935, elements of the workshop buildings, relocated amusement rides from Glenelg in South Australia, and new buildings, structures, and attractions were assembled on the sites of former erecting shops and staging wharves (fig. 8.2). The resulting new attraction, Luna Park, became a popular recreation venue for generations of Sydney residents and visitors (). Over the years, the rides and amusements have come and gone. Artworks and structures have been repaired, maintained, and sometimes updated, but throughout the strong visual character and iconic elements, such as a jovial laughing face flanked by two scalloped towers, fantasy architecture in a vaguely Moorish style, and many examples of pop art, have been constant. Luna Park developed strong associations with such well-known artists as Rupert Browne, Arthur Barton, Sam Lipson, Peter Kingston, and Martin Sharp (). Day and night the place smiles in a cheeky fashion across the waters beneath the Sydney Harbour Bridge at the Sydney Opera House; its color, humor, and movement distinguish Luna Park from every other harbor landmark.

Figure 8.2

Figure 8.2Following a fire at the Ghost Train attraction in 1979 (in which five people lost their lives), Luna Park was closed and then reopened a number of times as its owners struggled to remain commercially viable and contemplated development opportunities, until the lease on the site was resumed (compulsorily acquired) by the New South Wales State Government on the basis that the place was an important community asset for the people of Sydney (). In 1995, following the preparation of a conservation management plan, removal of hazardous and structurally defective material, and extensive reconstruction, Luna Park reopened under the management of a state-government-appointed trust, only to close a few years later, then reopen again in 2003 under private-sector stewardship through a new lease, following further physical changes, including the introduction of additional restaurant and event facilities, plus ride replacements, reconstruction, and upgrades, all of which were guided by a values-based approach and the conservation plan. The place has continued to operate under this arrangement in the period since, although a new conservation management plan, which reflects the current circumstances of the site, was prepared in 2015 ().

Unusually, the primary heritage values of Luna Park vest not in original historic fabric, but rather in its concept, design, and traditional use. What is most important about it is its role as part of the “collective childhood” of Sydney and the memories and meanings that the place and its iconic features have in the minds and hearts of Sydneysiders. These values are reflected in the following extract from the official State Heritage Register statement of significance:

Luna Park is important as a place of significance to generations of the Australian Public, in particular Sydneysiders who have strong memories and associations with the place. Its landmark location at the centre of Sydney Harbour together with its recognisable character has endowed it with a far wider sense of ownership, granting it an iconic status. (, n.p.)

The unusual circumstances of Luna Park and the nature of the attributes that encapsulate its heritage values require an equally unusual approach to conservation. Over the first half century of Luna Park operations, there were incremental changes and periodic upgrades of buildings, rides, and amusements. For example, during the 1930s and 1940s, the entrance Face, which was first built from ephemeral materials such as chicken wire, plaster, and papier-mâché, changed its appearance slightly with every round of maintenance (fig. 8.3). Rides came and went, but the core layout, major architectural elements, iconography, and amusement park use continued. By the 1990s the structural condition of some buildings and the imperative to remove hazardous materials, such as asbestos cement sheeting, had resulted in total reconstruction of the major buildings—the Face, Crystal Palace, and Coney Island—with each remaining faithful to a known earlier design, color scheme, and external appearance. The only original elements to be kept were some steel structures, interior murals, a few historic ride attractions, and minor decorative components (fig. 8.4).

Figure 8.3

Figure 8.3 Figure 8.4

Figure 8.4The new interventions—which far exceed the usual scale of physical conservation for historic places—are the key to a viable and enduring future. Very little authentic original 1930s, or even pre-1990s, built fabric remains, yet, paradoxically, the authenticity and integrity of Luna Park has been retained. Intangible attributes—the traditional amusement park use, distinctive visual appearance, and ability to evoke powerful memories—are essential to the social values of the place. Consistent with the Burra Charter methodology, it is these uses and associations and memories, rather than historic fabric, that remain constant, thereby retaining Luna Park’s social values and guiding its conservation.

Continuing use as an amusement park is an essential aspect of the heritage value of Luna Park. The Burra Charter overtly recognizes that use can be an important cultural attribute and that adaptation may be necessary to retain cultural significance:

Where the use of a place is of cultural significance it should be retained. (Article 7.1)

A place should have a compatible use. (Article 7.2) ()

At Luna Park, retention of heritage value through use of the place relies on the ongoing presence of rides and amusements. However, like any other amusement park, Luna Park must regularly refresh its offerings so that its clientele may enjoy new, exciting experiences. Developments in both technology and materials mean that new rides provide greater thrills than the rides available in the mid-twentieth century. Increased safety standards may require existing traditional rides to incorporate new safety features. Changes are inevitable. Luna Park’s approach to these constraints is unusual: by maintaining the characteristic layout, and including “nostalgic” elements, which reflect the spirit of the traditional rides, the contemporary Luna Park retains its identity and values while accommodating other factors such as market context and changing statutory requirements. So, while the distinctive built form and configuration of Luna Park is maintained, different buildings, structures, rides, and amusements may come and go.

The manner in which original significant elements have been treated since the 1990s accords with the applicable principles of the Burra Charter:

Restoration and reconstruction should reveal culturally significant aspects of the place. (Article 18)

Reconstruction is appropriate only where a place is incomplete through damage or alteration, and only where there is sufficient evidence to reproduce an earlier state of the fabric. In some cases, reconstruction may also be appropriate as part of a use or practice that retains the cultural significance of the place. (Article 20.1) ()

Physical conservation work on existing structures follows these principles, recognizing that most significant elements at Luna Park are already reconstructed.

With regard to the aforementioned factors, the new conservation management plan includes the following statements in the general policy for the conservation and management of Luna Park:

Luna Park should be operated as a traditional amusement park, and should include original rides and amusements, while also allowing for change such as refurbishment and updating of existing rides and installation of new rides …

Components from all periods of the history of Luna Park contribute to its heritage significance.

Much of the essential significance of Luna Park is symbolic and derives from the concept and design of built elements and decorations. Where physical factors prevent the retention of fabric identified as significant, new fabric may be introduced to enable reconstruction of significant elements …

The history and significance of Luna Park should be made accessible to visitors, passers-by and others through both on and off site interpretation. (, 41–42)

These policies directly address the importance of the use of the place, providing a framework to manage adaptation while conserving heritage values. In this context, adaptation may involve additions to the place; the introduction of new facilities, amusements, rides, or services; or changes to safeguard the place itself and the people who visit. The policy approach is thereby founded on the values framework of the Burra Charter, rather than presuming that physical conservation is paramount.

The BIG DIG: On The Rocks

In 1994, archaeological investigations in The Rocks—a historic precinct immediately north of the modern city of Sydney—revealed an extraordinary physical record of one of Australia’s earliest colonial settlements. Today this site, which became known as the BIG DIG, is home to a bustling youth hostel and archaeology education center operated by YHA Australia. Remarkably, the adaptation and development of this site has enabled in situ conservation and interpretation of extensive foundations and other remains associated with the community that lived here for a century following the first arrival of European settlers on the Australian continent. The youth hostel project accommodated multiple, interwoven heritage values and development issues: archaeology, physical conservation, social significance, engagement with stakeholders, public-private interface, and tension between economic and heritage values (fig. 8.5).

Figure 8.5

Figure 8.5The BIG DIG site is located between Cumberland and Gloucester Streets on a rocky ridge projecting into Sydney Harbour on the western side of Sydney Cove. It was here that Europeans stepped ashore when Australia was invaded and colonized in 1788, and for the ensuing two decades it was a place where resourceful convicts were permitted to build small dwellings. As the settlement grew, intensification saw the erection of small terraces and, later, large-scale maritime facilities, bond stores (warehouses), and merchant houses (). By the end of the nineteenth century there were numerous buildings, including rows of terrace housing, three hotels, and a bakery. However, following the arrival of bubonic plague, the area was resumed by the state government, the buildings were demolished, and the physical remains from early colonial times were buried. The site was variously used for industrial purposes and as a car park over the course of the twentieth century, and the structures and other physical remains from early colonial times remained buried and largely forgotten until archaeological investigations in 1994 (; ).

The archaeological investigations were initially directed at determining the nature and extent of any surviving features, in advance of development. However, over the course of several months of painstaking work, the archaeological team and hundreds of volunteer participants uncovered a rich chronicle of early Sydney that far exceeded all expectations: intact streets, substantial building remains, landscape features, extensive undisturbed historical deposits, and hundreds of thousands of artifacts. It was soon realized that the site provided extremely rare surviving evidence of the convict and ex-convict community established on The Rocks at the time of Australia’s first European colony and is “one of few surviving places in The Rocks where a substantial physical connection exists to the time of first settlement, including the huts and scattered houses built on and carved into the sandstone outcrops that gave The Rocks its name” (, n.p.).

The BIG DIG site retains historic associative values arising from a combination of documentary and physical evidence of historic events, processes, and people. Other heritage values changed over the course of the archaeological investigation project, with archaeological potential (often characterized as “scientific value”) being realized and other values being generated. These include the aesthetic qualities of the evocative ruins that were exposed, newly created social values arising from the public perceptions that followed community involvement and media interest, as well as the educational value of the place, the artifacts, and the related documents and knowledge. The site provides a compelling example of the mutable quality of heritage values.

For more than a decade after the major phase of on-site investigations, and following abandonment of plans for commercial development, the BIG DIG site lay idle until YHA Australia secured the opportunity to build a youth hostel and archaeology education center. While the core business of YHA Australia is hostels, the ensuing success of the enterprise was founded on realization of the potential synergy between low-cost accommodation in the heart of a major city and the opportunity for “hands on” experience of Sydney’s history, which arose from the high interpretive and educational potential of the place. This realization, in turn, drove a values-based design approach using the Burra Charter framework.

No attempt was made to reconstruct or rebuild any former structures. Instead, the archaeological team carefully assessed and mapped every feature on-site and graded its relative heritage significance, based on judgements of historic association, aesthetic quality, research, educational potential, and physical integrity. This plan—based on heritage values, rather than the client’s operational brief—set the framework for the design of the building above, particularly its structure and foundations ().

The resulting built form touches down on less than 5 percent of the remnant archaeological site; the matrix-like steel frame uses techniques such as cross bracing and transfer beams to avoid significant features. Every ground disturbance required for construction was hand excavated, using the same methods and research framework as the original excavations. An impervious platform built across the site prevented inadvertent damage from spills or unauthorized interventions during the construction phase.

The three modern structures all occupy areas where previous buildings and their external facades aligned with historic streets. In places these are interpreted using metal screens and historic images (fig. 8.6a and fig. 8.6b). Externally, the buildings present as new elements of contrasting but sympathetic design within the surrounding late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century streetscape. Voids within the hostel buildings provide views of remains, which are interpreted through signs, historic images, and artwork. Other devices, such as the naming of rooms, artifact displays, and wire sculptures contribute to the multiple levels of message and meaning conveyed to visitors.

Figure 8.6a

Figure 8.6aThe BIG DIG Archaeology Education Centre component of the project has proven an outstanding success. Built as a separate structure, also straddling archaeological features below, the center includes two classrooms, school facilities, a mock archaeological dig, and a separate viewing area where students can see excavated parts of the site. There are a range of different school programs offered for both primary and secondary students, some of whom make use of the site-specific education kit, excavation reports, published works, and real artifacts as part of their program (; ; ). The adjacent hostel provides accommodation for regional schools. In 2016 the BIG DIG Archaeology Education Centre welcomed its fifty-thousandth student. The facility is also regularly used as a meeting and conference venue.

The project is underpinned (literally and metaphorically) by founding the concept and design on the values of the place; both redevelopment and use have been values driven, combining conservation and modern infill in a sensitive urban context. These innovations have been widely recognized with multiple national awards in fields as diverse as architecture, urban development, heritage conservation, tourism, and archaeology, as noted in the official state heritage listing citation:

The sensitive construction of a Youth Hostel (YHA) over the archaeological site and integrated interpretation of this archaeological site has received multiple awards in design and heritage. The YHA development has been described as arguably one of the best contemporary examples of in-situ conservation of archaeological remains in an urban context anywhere in the world. (, n.p.)

Willowdale, East Leppington

Over the course of nearly forty years, the Burra Charter has been successfully applied to an increasingly wide range of cultural place types and issues. Originally drafted by practitioners who were predominantly involved with historic sites, the charter was always intended to encompass diversity, ranging from cathedrals to archaeological ruins, shipwrecks to gardens. Since the revisions in 1999, however, it has become increasingly relevant to cultural resource management decisions for Indigenous heritage and, more recently, in contexts that involve multiple natural and cultural values and the emergent sustainability agenda. A major land development project at East Leppington, on the Cumberland Plain in western Sydney, offers an informative example.

Before addressing the specific place and project, it is important to understand that for many Indigenous Australians the notion of “connection to Country” and the intangible ties that bind them to the ancient land for which they speak are paramount to Indigenous identity, well-being, and intergenerational cultural traditions. Chris Tobin, a Darug man from western Sydney, puts this eloquently:

As Aboriginal people our identity is inseparable from our Country. We are the people of that Country. It holds our stories, provides food and medicine to our bodies and spirit and it has been home to our people for all recorded history, as it has been home to our ancestors for tens of thousands of years. (, 78)

A land development project at East Leppington considered both the scientific values of Indigenous archaeology and the values and perspectives of Traditional Owners, combined with natural values assessment, to determine how open space is deployed and new “places” are created. In the greater Sydney area, new large-scale land releases have seen an area that was formerly a greenbelt of agricultural land rezoned and made available for housing development. In the past, such land releases were usually undertaken without specific consideration of Indigenous heritage sites or places, and have resulted in widespread impact to previously unrecorded sites and inadvertent loss of cultural connections with Country. The East Leppington precinct (now also known as Willowdale) was approached from a different perspective. This land release and consequential development by property development company Stockland Ltd. sought to understand all of the heritage values of the area as crucial input to the urban planning process (; , 114).

Understanding the cultural values of the Willowdale precinct was a multistage, interactive process commencing with research on the geophysical resource—geology, geomorphology, ecology, and landscape—and initial desktop study and predictive modeling of archaeological potential. Consistent with the required process for evaluating and managing Indigenous heritage under NSW legislation and guidelines (), Indigenous people with connections to this Country were invited to register. Associated people from the Dharawal and Gundungurra language groups were then engaged in both consultative processes and field surveys. The predictive model was refined, and a program of archaeological test excavation across a broad area followed. During this process, employment opportunities were offered to representatives from the Indigenous communities (fig 8.7). These investigations revealed an extensive archaeological landscape containing extensive artifact scatters and identified scientifically important features and deposits, including earthen structures believed to be cooking ovens ().

Figure 8.7

Figure 8.7The involvement of Dharawal and Gundungurra people in the process simultaneously provided them with opportunities to reconnect with Country in a tangible manner and, through employment on-site, to receive some benefit from the processes arising from the management of their cultural heritage in a development context. At the same time, the research and scientific framework of the archaeology enabled the research potential of the landscape to be realized and demonstrated its scientific research potential. The consultative process undertaken with registered Indigenous stakeholders identified that, in addition to the physical evidence provided by archaeological features, the Willowdale precinct had other associative values arising from attributes such as views and stories connected to the landscape.

Work with Stockland’s design team resulted in an urban design that recognized and included the key heritage attributes and values, both tangible and intangible (). The provision of detailed heritage evidence facilitated conservation outcomes and informed the character of the final design (). A range of landscape features and community facilities have been incorporated within the land release. These include, for example, the lookout knoll, a park that was specifically established to conserve intangible values associated with the function of this hilltop and the associated view corridors to the nearby Blue Mountains (fig. 8.8). Creation of this park, and the retention of this land in an undeveloped state, was of major importance to the Traditional Owners who spoke for this Country and their associated local community. The process of establishing the park involved a meeting of Indigenous elders, who defined limits to the extent of permissible development based on cultural knowledge. Once this extent was determined, the open space requirement was incorporated within a “development control plan,” which sets parameters for development on the upper slopes of the hill, conserving the place and its associated view lines and stories. Through these processes the land release, rather than impacting upon traditional culture, has reestablished and strengthened connections between local Indigenous people and this Country and reinforced the principle that Indigenous people enjoy a right to participate in decisions that affect their culture and heritage.

Figure 8.8

Figure 8.8Other components of the development were also driven by an approach that commenced with establishing heritage values and then accommodating these within the framework of other project constraints and objectives. Proposed sports fields were carefully sited to enable Indigenous archaeological deposits to be capped and conserved for posterity (whether for the benefit of future Indigenous communities, for researchers, or for both) beneath a covering of clean fill. Recognizing the interconnection of natural and cultural values, conservation areas along riparian corridors were configured to protect both natural species and archaeological deposits. Two local parks were re-sited to provide greater retention of known sites and associative Indigenous values. A permanent conservation zone was dedicated to protect a known site that had previously been saved through intervention by an Indigenous Elder.

These activities have all occurred in a rapidly growing area on the urban periphery that has high real estate value and strong demand for new development opportunities, yet the very substantial conservation outcomes are perceived as enhancing the new development and the reputation of the developer, rather than adversely affecting property yields.

The process and outcomes demonstrate cultural heritage conservation, using the Burra Charter methodology, across multiple value sets at a landscape scale. The approach also addresses emerging innovation challenges and concepts by prioritizing as values attributes that the property development community had previously regarded as constraints, namely culture, heritage, and identity. The approach taken identified and conserved both tangible and intangible Indigenous heritage values within the new Willowdale precinct (), thereby also delivering results that contribute to the wider objective of Aboriginal “reconciliation.” The project has been nominated under the Green Star—Communities rating tool within the innovation category (), a nomination that highlights how recent developments in Australian sustainability ratings systems are commencing to recognize the intergenerational “inheritance” values of culture to a sustainable future, rather than only recycled materials and/or measures of energy performance.

Conclusion

Like the places whose conservation and management it guides, the Burra Charter is itself evolving and changing to suit changing circumstances and different contexts. In a strange quirk of fate, when changes to the Burra Charter were first proposed at a special meeting of Australia ICOMOS purposefully convened at the Burra Town Hall in November 1997, nearly twenty years after the charter’s adoption, the revision was not accepted, as the level of change proposed was considered too extensive, such that the core value of the charter was at risk. In a submission about the draft, this author dryly observed:

The level of change is too great. Might I suggest, somewhat facetiously, that the redrafting has itself not followed two essential principles; i.e., it has not identified and retained the significant elements of the previous Charter—thereby losing its fundamental essence and, secondly, it has not followed the cautionary principle it advocates. (, 35)

It would be another two years before the amendments, which provided greater recognition of intangible attributes and the rights of associated people, would be adopted (). What is significant, however, is that although, in contrast to many doctrinal heritage guidelines, the Burra Charter continues to be amended and updated, its core principles and process remain firmly founded on understanding the place, assessing its values, identifying issues, and developing policies to address and manage the issues so as to retain the identified values (see fig. 8.1). It is this clarity that makes the Burra Charter flexible to suit different types of place and adaptable to respond to different statutory, financial, physical, or operational contexts. The charter’s approach is relevant to Luna Park’s “amusing” circumstances, where there is virtually no original fabric (but strong associative social values), and as a tool to discern values-based design constraints on the BIG DIG archaeological site or to manage Indigenous connection to Country at a landscape scale at Willowdale. The charter is aging gracefully, and its progressive phases of adaptation have been sympathetic to the original. Because it has evolved to meet emerging practice needs and to recognize shifting government and societal values and changing community perceptions, the Burra Charter remains a powerful and effective tool for making well-informed decisions about important cultural heritage places.

References

- Alexander Tzannes Associates and Godden Mackay Logan Pty. Ltd. 2006. “The Rocks Dig Site, Sydney Australia, Conservation Management Strategy and Archaeological and Urban Design Parameters.” Unpublished report for YHA Australia Ltd. Sydney.

- Allen, Caitlin. 2004. “The Road from Burra: Thoughts on Using the Charter in the Future.” Historic Environment 18 (1): 50–53.

- Astarte Resources, Godden Mackay Logan Pty. Ltd., and Historic Houses Trust of NSW. 2000. “The BIG DIG Kit.” Canberra: Astarte Resources.

- Australia ICOMOS. 1999. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. 1979; rev. 1999. Burwood: Australia ICOMOS. http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/BURRA-CHARTER-1999_charter-only.pdf.

- Australia ICOMOS. 2013a. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. Burwood: Australia ICOMOS. http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf.

- Australia ICOMOS. 2013b. Burra Charter Practice Notes. Burwood: Australia ICOMOS. http://australia.icomos.org/publications/charters/.

- Australia ICOMOS. 2016. Collaboration for Conservation: A Brief History of Australia ICOMOS and the Burra Charter. Burwood: Australia ICOMOS. Accessed November 16, 2017. http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/Collaboration-for-Conservation-A-brief-history-of-Australia-ICOMOS-and-the-Burra-Charter.pdf.

- GML Heritage. 2012. “East Leppington Rezoning Report: Heritage Management Strategy.” Unpublished report prepared for the NSW Department of Planning and Infrastructure on behalf of Stockland Corporation Limited. Redfern, Australia: GML Heritage.

- GML Heritage. 2015. “Luna Park, Sydney Conservation Management Plan.” Unpublished report prepared for Luna Park Sydney Pty. Ltd.

- Godden Mackay Pty. Ltd. and Grace Karskens. 1999. The Cumberland Gloucester Streets Site Archaeological Investigation. 6 vols. Redfern, Australia: Godden Mackay Logan Pty. Ltd.

- Green Building Council of Australia. 2017. “Green Star Communities: Green Star Rating System.” Accessed May 18, 2017. http://new.gbca.org.au/green-star/rating-system/.

- ICOMOS. 1931. The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments–1931. [Paris]: ICOMOS. http://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments.

- ICOMOS. 1965. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter 1964). [Paris]: ICOMOS. https://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf.

- Karskens, Grace. 1999. Inside The Rocks: The Archaeology of a Neighbourhood. Sydney: Hale and Iremonger.

- Mackay, Richard. 2004. “Associative Value and the Revised Burra Charter: A Personal Perspective.” Historic Environment 18 (1): 35–36.

- Mackay, Richard. 2005. “Archaeology: Stories and Contemporary Social Context.” Historic Environment 18 (3): 27–30.

- Mackay, Richard. 2015. “The Contemporary Aboriginal Heritage Value of the Greater Blue Mountains.” In Values for a New Generation: Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, edited by Doug Benson, 78–95. Katoomba, Australia: Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area Advisory Committee. Accessed November 16, 2017. http://www.naturetourismservices.com.au/threesisters/values-for-new-generation2.pdf.

- Mackay, Richard. 2017. “Heritage: Australia State of the Environment 2016.” Canberra: Australian Government Department of the Environment and Energy. Accessed November 16, 2017. https://soe.environment.gov.au/theme/heritage#Executive_Summary_Heritage_2016.

- Mackay, Richard, and Chris Johnston. 2010. “Heritage Management and Community Connections: On The Rocks.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 16 (1): 55–74.

- Mackay, Richard, and Georgina Lloyd. 2013. “Capacity Building in Heritage Management at Angkor.” World Heritage Institute of Training and Research for the Asia and the Pacific Region Newsletter 26:21–24.

- Mackay, Richard, and Stuart Palmer. 2014. “Tourism, World Heritage and Local Communities: An Ethical Framework in Practice at Angkor.” In The Ethics of Cultural Heritage: Memory, Management and Museums, edited by Tracy Ireland and John Schofield, 165–83. New York: Springer.

- Marshall, Sam. 2005. Luna Park: Just for Fun. 2nd ed. Sydney: Luna Park Reserve Trust.

- NSW Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. 2010. Due Diligence Code of Practice for the Protection of Aboriginal Objects in New South Wales. Sydney: Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW. Accessed November 16, 2017. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/cultureheritage/ddcop/10798ddcop.pdf.

- NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. 2017a. “State Heritage Database: Cumberland Street Archaeological Site.” Accessed May 20, 2017. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5056816.

- NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. 2017b. “State Heritage Database: Luna Park Precinct.” Accessed May 20, 2017. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5055827.

- Owen, Timothy D. 2015a. “Advocating Aboriginal Heritage Conservation and Management through the Land Development Process: An Example from New South Wales, Australia.” In International Austronesian Conference Proceedings. Territorial Governance and Cultural Heritage, 186–204. Taipei: Council for Indigenous Peoples and the National Taipei University of Education.

- Owen, Timothy D. 2015b. “An Archaeology of Absence.” Historic Environment 27 (2): 70–83.

- Poulios, Ioannis. 2010. “Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 12 (2): 170–85.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Sullivan, Sharon, and Richard Mackay, eds. 2012. Archaeological Sites: Conservation and Management. Readings in Conservation Series. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Truscott, Marilyn C. 2004. “Contexts for Change: Paving the Way to the 1999 Burra Charter.” Historic Environment 18 (1): 30–34.

- Waterton, Emma, Laurajane Smith, and Gary Campbell. 2006. “The Utility of Discourse Analysis to Heritage Studies: The Burra Charter and Social Inclusion.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12 (4): 339–55.

- Zancheti, Sílvio Mendes, Lúcia Tone Ferreira Hidaka, Cecilia Ribeiro, and Barbara Aguiar. 2009. “Judgement and Validation in the Burra Charter Process: Introducing Feedback in Assessing the Cultural Significance of Heritage Sites.” City and Time 4 (2): 47–53. http://www.ct.ceci-br.org/novo/revista/viewarticle.php?id=146.

| words