5. The Shift toward Values in UK Heritage Practice

- Kate Clark

In the years since the Getty Conservation Institute’s Research on the Values of Heritage project (1998–2005) there has been a noticeable change in the extent to which thinking about heritage values has been incorporated into heritage policy and practice within the UK.1 This chapter provides a perspective on that transformation, exploring three kinds of heritage values reflected in three phenomena: first, changing ideas about significance in the protection and management of heritage (so-called intrinsic values, relating to significance); second, growing awareness of the wider economic, social, and environmental benefits of heritage (instrumental values, relating to sustainability); and third, the exploration of how heritage organizations themselves create value (institutional values, related to service).2 It draws on some policy developments, mainly in England between 2000 and the present day, in particular the publication of the English Heritage (now Historic England) Conservation Principles in 2008, which put in place a transparent values-based decision-making process for heritage, and the work of the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), which has gone beyond formally protected or listed heritage to engage with a wider range of people and types of heritage in the UK.3

Significance: Using Values in Designation and Decision Making

The journey toward thinking more explicitly about values in heritage practice begins with the idea of significance. There is nothing new about the concept of significance in heritage. Every decision to preserve something for the future is based on some perception of value. To take a random example: the tooth of a great white shark was recently excavated at a late Bronze Age midden site at Llanmaes in Wales. It had clearly been transported over a great distance, and its location—deposited in a post hole—implied that it had had special meaning to somebody in the past ().

Equally, every decision to preserve a heritage asset for the future is based on an individual or collective perception of value. When discussing what should be preserved, the influential nineteenth-century pioneer of British conservation, William Morris, answered:

If for the rest, it be asked us to specify what kind or amount of art, style, or other interest in a building, makes it worth protecting, we answer, anything which can be looked on as artistic, picturesque, topical, antique, or substantial: any work, in short, over which educated, artistic people would think it worth while to argue at all. (, n.p.)

The first legislation to protect monuments in the UK was finally enacted in 1882, after nearly a decade of attempts. How things were to be judged important was a matter of concern from the outset. One of the main objections to the bill was that by preserving monuments, this was a proposal to “take the property of owners not for utilitarian purposes, for railways and purposes of that sort, but for purposes of sentiment, and it was difficult to see where they would stop” (, 27). The objections of property owners held sway, and the final form of the 1882 Ancient Monuments Protection Act was very much watered down in terms of powers to interfere with property rights. In relation to values or “sentiment,” the act did not define ancient monuments or their significance, except by implication in that they were of “like character” to those in the schedule or list attached to the act (mainly prehistoric monuments) (, 5). Their significance was explained to Parliament during the debate: “As to the value of which … there was an agreement among all persons interested in the preservation of ancient monuments” (, 29).

As Harold Kalman notes, one of the fundamental elements of European-derived heritage legislative systems is the idea of a list, register, or inventory that recognizes places of merit, and it is possible to trace the evolution of that concept of “merit” through different forms of legislation (, 48). For example in the United States, the American Antiquities Act of 1906 extended protection to “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic and scientific interest,” although these were confined to federally owned or controlled land (, sect 2). In the UK, ancient monuments are currently defined as being of “national importance” under the 1979 Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act (, part 1, sect 1.3; ). In the UK, heritage protection was extended to historic buildings following the destruction of World War II. Under the system of “listing,” historic buildings need to be of “special architectural or historic interest” (, ch. 1.1; ).

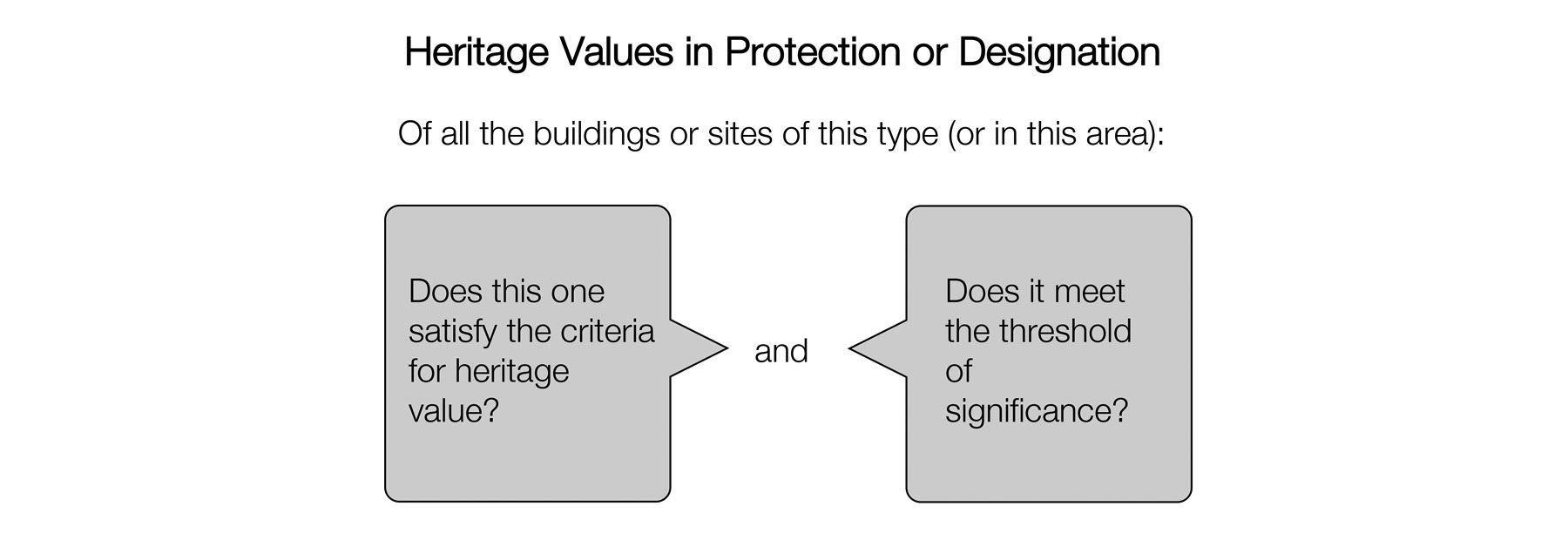

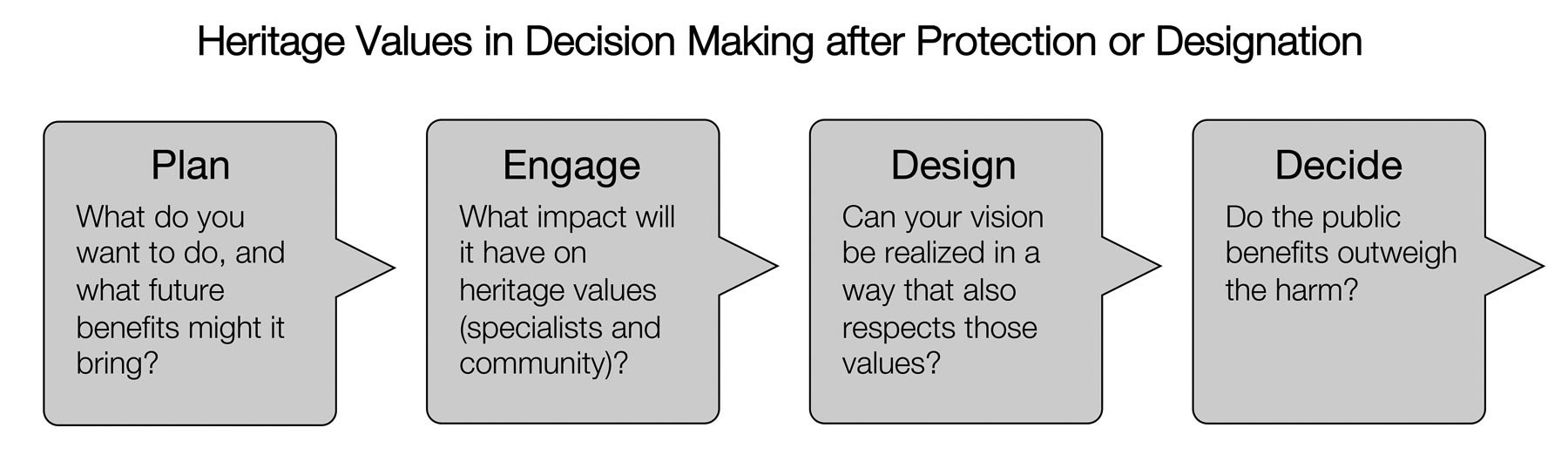

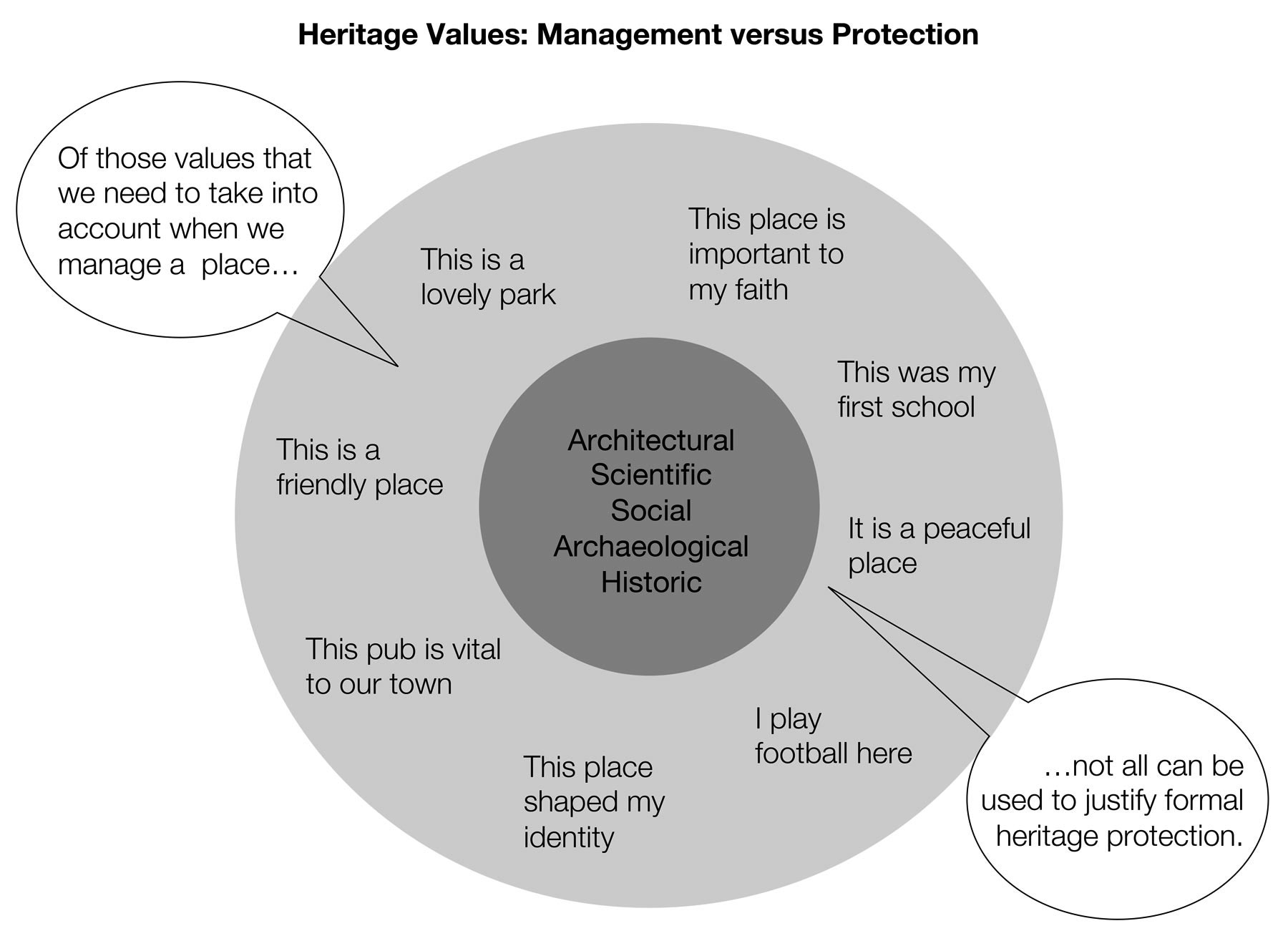

As well as informing decisions about what to protect, values also come into formal heritage practice after a site has been protected where there is a process of managing change, for example if an owner wants to alter or demolish a property (fig. 5.1a and fig. 5.1b). It is in this area of decision making that the most overt move toward thinking about heritage values has taken place. Decisions about change to individual heritage assets are usually made at a local level, by planning authorities who need to set the special heritage interest of the site against other values, including wider economic, social, and environmental issues, and of course the ambitions of the owner. This is why making decisions about changes to historic buildings, monuments, and places after they have been designated has always been more complex and involves a wider range of values than choosing places to protect (fig. 5.2).

Figure 5.2

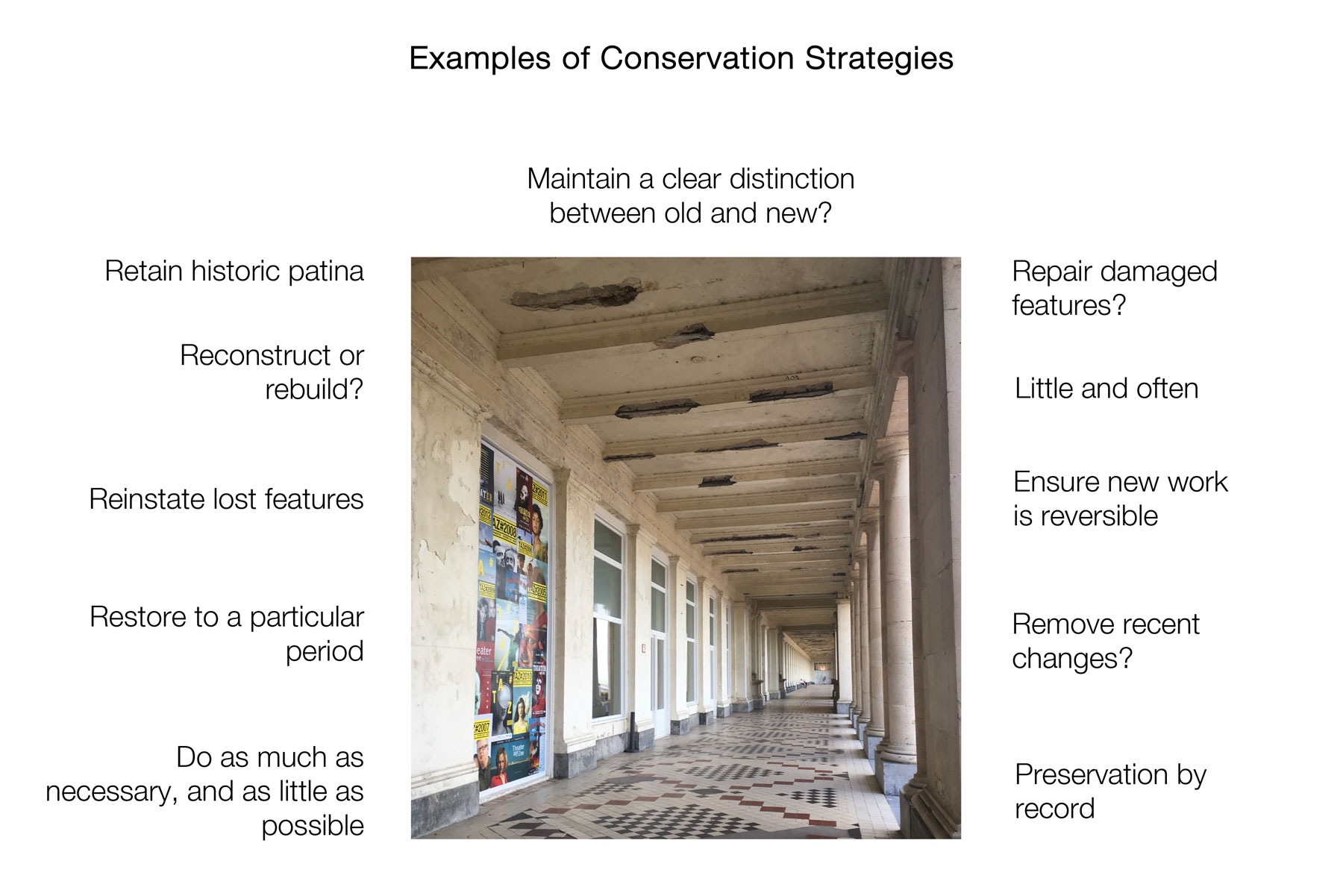

Figure 5.2In the mid-1990s, two key UK government documents guided decision making about heritage assets after they were designated in England: Planning Policy Guidance 15, which covered listed buildings, conservation areas, and other heritage sites (), and Planning Policy Guidance 16, covering archaeology (). Both documents sought to show how heritage should be protected as part of the planning system. Although both address the need to take the reasons for which the heritage has been protected into account in decision making (significance), they do so largely by providing guidance on different ways to do this. For example, PPG 15 defined appropriate uses, the importance of repair, issues to be taken into account in considering demolition, and the treatment of specific building elements. Underlying this was the philosophy of minimum intervention, carrying forward Morris’s deep-seated reaction against the nineteenth century’s restoration movement and the scraping away of layers of history, which saw so many historic buildings effectively rebuilt in the interests of re-creating their putative earlier form. For archaeological sites of national importance, where there was a presumption in favor of preservation, PPG 16 showed how to achieve that through strategies such as preservation by record.

The move toward a more explicit values-based decision-making process came with the publication of the English Heritage Conservation Principles in 2008 (). As noted at the outset, the idea of significance was not new, and the requirement to consider significance was there in the PPGs and other guidance, such as that on management planning for World Heritage Sites, but what was different was the more explicit approach to using values in decision making. The principles aimed to support quality in decision making, with the ultimate objective of “creating a management regime for … the historic environment that is clear and transparent in its purpose and sustainable in its application” ().

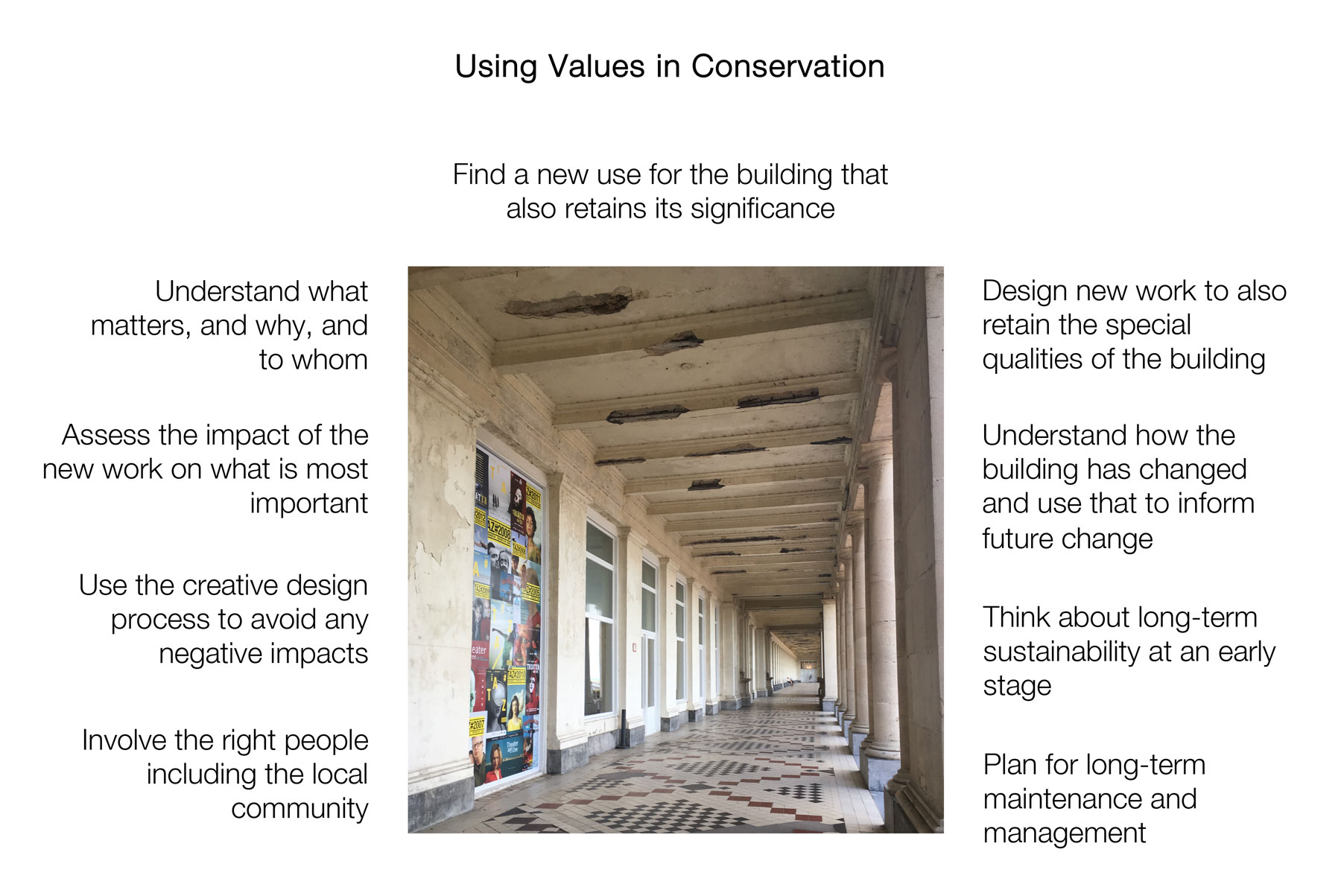

The core values identified in the principles are evidential, historical, aesthetic, and communal. The guidance on assessing significance describes the process: understanding the fabric and evolution of the place; identifying who values the place and why they do so; linking values to fabric; thinking about associated objects and collections, setting, and context; and then comparing the place with others sharing similar values. It is a process that grounds value in fabric in order to help make decisions about what can be changed and what cannot ().

The Conservation Principles signaled a move from decision making based on strategies or recipes (such as minimum intervention, no restoration, presumption on preservation, and treatment of specific elements—values that derive from conservation as a discipline) toward a decision-making process that also had space for the different ways in which heritage mattered to the general public (fig. 5.3a and fig. 5.3b). They marked the first time that a major heritage agency in the UK explained how it expects values to be taken into account in decision making as part of the statutory process.

The values-based approach was now a core part of established conservation thinking in the UK. In Wales, Cadw (the Welsh government historic environment service) published conservation principles in 2011, again putting value and understanding significance at the center of conservation (), while the Historic Environment Scotland conservation principles explicitly state that “the purpose of conservation is to perpetuate cultural significance” (, 3).

The Impact of the Heritage Lottery Fund on Thinking about Heritage Values

What had happened between 1994 and the publication of the Conservation Principles in 2008 to inspire this move toward values-based thinking?

To some extent trends in heritage reflected a wider move toward recognizing the value of greater community involvement, emerging from both the philosophy of sustainable development (see below) and also wider government policy on social inclusion. In planning, the 1990s witnessed a decisive move toward participatory planning and place making. “Citizen science” was embraced by natural heritage, museums were opening up to wider participation, and in other areas of the arts such as theater and opera, community-based events were becoming more popular.4

The biggest influence on heritage practice in the UK was financial. The Heritage Lottery Fund provided new sources of funding, and with it a new approach to heritage. Set up in 1994 to fund heritage projects using money from the National Lottery, it was a very different organization from the national heritage bodies in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. As a funder and not a regulator, HLF also had a distinctive philosophy. Most importantly, it was set up to fund a very broad range of heritage that went beyond sites and buildings to include museums and archives, biodiversity, industrial heritage, landscapes, and intangible heritage such as oral histories and memories. And because it did not have a regulatory function, it was much freer to explore different approaches to heritage and was not tied to any single legal or policy framework.

With up to £300 million per annum, it soon developed robust funding procedures to ensure that grants were distributed fairly and spent well. The emphasis was on developing procedures for successful projects, whatever kind of heritage was involved: business planning, ensuring access, developing skills, and long-term sustainability. Critically, the Heritage Lottery Fund also recognized the centrality of involving people in heritage activities. There was a huge emphasis on access and engagement, as well as audience development (). The fund could support activity projects such as public programs and events or arts activities, as well as the physical repair or conservation of sites.

Another critical aspect of the HLF approach was that it broadened the idea of heritage beyond protected sites. By not confining its financial support to protected sites of high significance (whether cultural or natural) and instead asking applicants to demonstrate how and why the heritage was important to them, HLF opened up opportunities for different communities whose heritage had not previously been recognized or acknowledged through official designation to research, discover, and indeed protect their own stories. These included different ethnic and faith communities, communities with stories that had not been told (the history of disability, for example), and even parts of Britain that felt that their own area or story had not been celebrated. The HLF took the thinking about heritage values beyond the kinds of value enshrined in the heritage protection legislation to embrace a much more diverse range of values.

When deciding what to fund, the application process also, controversially, changed the relationship with heritage specialists by placing the onus on applicants and communities to make a values-based argument rather than relying on the judgment of specialists with a background in the traditional heritage disciplines. National organizations such as English Heritage, Cadw, and Historic Scotland had historically given grants for buildings based on “outstandingness” or the quality of the building. HLF’s new approach did not necessarily disregard the quality of the heritage, but it brought a much wider range of values into play when making decisions about projects.

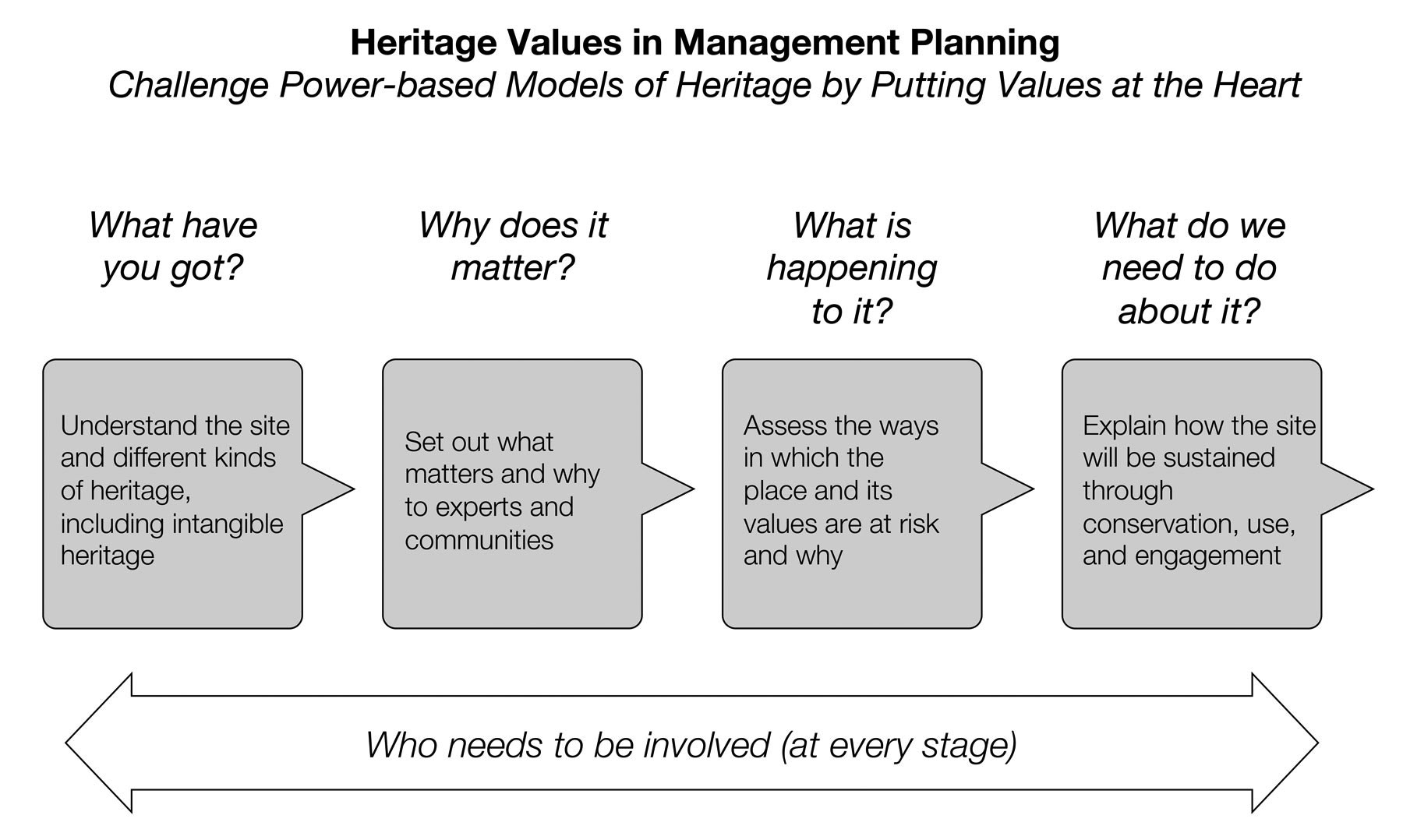

HLF also influenced the agenda on heritage values by introducing an explicitly values-based planning process (fig. 5.4). Applicants seeking large capital grants for major projects that could have a big impact on a heritage site, such as new visitor centers or major repair programs or interventions, were asked to prepare conservation management plans (). These plans were part of a suite of other project information (business plans, access and audience development plans) designed to help ensure that projects were properly thought through and would be sustainable. Smaller projects were not asked for such plans, but as part of the application process they were still asked to explain the value of the site.

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4The HLF guidance on conservation plans drew on the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance (or Burra Charter) process but adapted it.5 The original guidance went well beyond significance in the sense of the formal reasons for which a site was designated and asked planners to explore all of the different ways in which people valued the place, including the perspectives of different communities. The planning process used that understanding of value in order to help set out how the site would be managed and sustained in the future, ensuring that community values would be taken into account in future thinking.6

The values-based process was not without critics. For instance, at a conference in 1999 to debate the use of such plans, there was a lot of concern that time and money spent on planning would distract attention and funding from the core work of repairing sites and buildings (). Indeed, many plans submitted to HLF for review showed that some practitioners struggled with the HLF requirements to go beyond the formal reasons for which sites were protected and to engage with wider communities and what mattered to them. They also struggled to see how understanding value might shape how a site would be managed.

Sustainability: The Instrumental Economic, Social, and Environmental Benefits of Heritage

The English Heritage Conservation Principles also placed heritage decisions within the context of sustainability. Sustainability is the second (and parallel) trend in values-based heritage practice in the UK since the late 1990s, and involves recognizing the wider economic, social, and environmental benefits that flow from investing in heritage.

The difference between sustainability in the broadest sense and conservation in a narrow sense is that conservation is about repairing an individual site or building, while sustainability involves taking a wider view of that site, including finding a longer-term use to ensure its survival in the future. For people who work with heritage, thinking about sustainability often means finding connections between heritage and the wider context for heritage places, such as land-use planning, economic development, or social inclusion. The two approaches complement each other—there is little point in repairing or conserving a building without thinking about its long-term management, nor is there any point in thinking about the future of a site that has been almost totally lost.

In terms of the values agenda, thinking about sustainability requires heritage practitioners to have a good understanding of the potential economic, social, and environmental benefits of investing in heritage. That understanding helps make the connection between caring for heritage and other, wider policy objectives. It contributes to reducing the isolation of heritage by seeing it as part of a bigger narrative around place and environment.

Perhaps the key point at which ideas about sustainability—and with them broader ideas about the economic and social values of heritage—became part of formal heritage practice in England was during a major review of heritage policies in 2000. The government had asked English Heritage to review its policies for the historic environment. The organization undertook a major consultative exercise, convening a series of working groups that brought together people from heritage, the natural environment, business, and the arts. It culminated in the publication Power of Place: The Future of the Historic Environment and the government policy document A Force for Our Future (; ).

At the time, new thinking on sustainability was emerging from documents such as Caring for the Earth, published in 1991 by the World Conservation Union (IUCN), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), which argued that sustainability linked the environment and nature to society and economics, and was not just top down but bottom up; recognized that conservation did not take place in isolation; and drove home the importance of involving people. Ideas such as improving quality of life, keeping within the Earth’s carrying capacity, enabling communities to care for their own environments, and integrating development and conservation—originally developed for the natural environment—were applied to cultural heritage.

The legacy of that thinking and of Power of Place is evident in the way heritage practice changed over the next decade or so. Heritage policy became much closer to natural environmental policy, borrowing approaches and ideas, even down to the use of the term “historic environment” rather than “heritage” in policy documents and strategies. There were strategic initiatives to monitor and manage heritage at risk, including buildings and monuments at risk surveys, which mirror the natural heritage focus on endangered species. In 2002 English Heritage published a State of the Historic Environment Report, the first such annual review, which was similar to regular surveys of the natural environment tracking progress in conservation (). Subsequent reports were published under the title Heritage Counts. Heritage concerns became more closely integrated into environmental policies, impact assessments, and funding regimes such as agricultural subsidies. Even the move from individual species to habitats is mirrored in the move from individual buildings and sites toward more use of place-based and character-based thinking in heritage (). Initiatives such as the use of conservation management plans, and indeed World Heritage site management plans, encouraged people to think more widely about the value of heritage to different communities, while the emphasis on managing sites rather than just conserving them reflected thinking about sustainability.

In terms of values, sustainability brought a new emphasis on exploring the economic impacts and benefits of investing in heritage. HLF undertook a major program of economic impact assessments in order to try and capture the direct and indirect impacts of spending on heritage. English Heritage was also undertaking similar work, tracking for example the investment performance of listed buildings.

That move toward recognizing the role of heritage in the economy can also be seen in how organizations were prioritizing funding. As noted, in both England and Wales, grant funding programs moved from giving priority to highly significant individual buildings in need of repair to promoting more heritage-led regeneration schemes that brought new life to deprived areas. Townscape Heritage schemes (similar to US Main Street schemes) put as much emphasis on delivering economic benefit as on repairing significant buildings (). These developments were more than attempts to recast heritage language in the language of current government priorities. There was a genuine recognition that repairing historic buildings was not enough. It was also important to find sustainable uses for them. Recognizing the importance of finding viable uses for heritage buildings, HLF has since launched a heritage enterprise grants program designed to help community groups develop better business skills and find creative new things to do with empty buildings ().

The other more recent trend has been in recognizing the social benefits or values of investing in heritage. The idea of using museums and heritage sites for educational purposes is not new; indeed, participation data shows that visiting a heritage site when you are young is one of the biggest drivers for heritage visitation in later life. But over the last two decades, there has been an active move to use heritage as a force to combat social exclusion—where individuals or particular groups lack access to opportunities such as employment or civic engagement, or indeed heritage. It began with a move toward making heritage sites and buildings more physically accessible, but it goes well beyond that. HLF in particular has actively invited excluded groups to apply for funding, encouraging people to tell their own stories and to find and conserve sites that matter to them. It has funded initiatives such as the Anglo-Sikh Heritage Trail to promote greater awareness of the shared heritage between Britain and India and sites of importance to the Sikh community across the UK, or the Royal Mencap Society project on the hidden heritage of people with learning disabilities.7

The heritage sector has been inching into health, too, with projects involving homeless people or ex-servicepeople (veterans). Operation Nightingale has been supported by the Ministry of Defence and is helping soldiers injured in Afghanistan return to their regiments or prepare for civilian life using archaeological field projects, including excavation, land survey, drawing, and mapping. In Wales, the Fusion program brings social services providers together with museums and heritage organizations. Very small amounts of funding go to the social services providers, but it has a huge impact, as they begin to see how heritage can help them get young people back into education or reach families who have become isolated.

Over the past fifteen years, heritage organizations in the UK, from museums to funders, advocacy bodies, and site managers, have all recognized that engaging with wider social and economic agendas through understanding the social and economic benefits of heritage, and delivering projects that focus on those outcomes, is a core part of what they do. Prior to its recent reorganization in 2015, English Heritage developed the concept of a “virtuous circle,” based on the conservation principles under the banner of “constructive conservation.” The virtuous circle posits:

By understanding the historic environment people value it; by valuing it they will want to care for it; by caring for it they will help people enjoy it; [and] from enjoying the historic environment comes a thirst to understand it. (, 10–11)

Values in Heritage Organizations

The third trend in UK values-based heritage practice over the past fifteen years is evident in how values are reflected in heritage practitioners’ and organizations’ behavior. For individual practitioners, the issues are generally related to ethics in practice (not explored in any detail here), but for organizations the picture is more complex. For heritage organizations, the fundamental question is how to demonstrate the value of what they do. Is it something quantitative that can be measured in terms of targets for performance, such as the number of sites conserved by a funding organization, the number of decisions made by a regulatory organization, or the number of visitors to a museum? Or is the value created by the existence of a heritage organization something less tangible?

These were the questions HLF faced in 2006, driven in part by the need to demonstrate the case for the renewal of its operating license, but also by a growing realization that it was important to be able to explain exactly what such a large investment in heritage had achieved. The fund already had in place an active program for evaluating the impact of its funding, including studies that looked at the benefits of specific programs (such as funding for public parks or for townscape heritage schemes). The HLF also captured a variety of quantitative data about its funding, including data about the geographical distribution of funding across different regions, the different types of heritage funded, and the spread of funding across different grant sizes. The result was a huge bank of social, economic, and spatial data about heritage, but there was no single model to explain the wider value of what the fund had done or created.

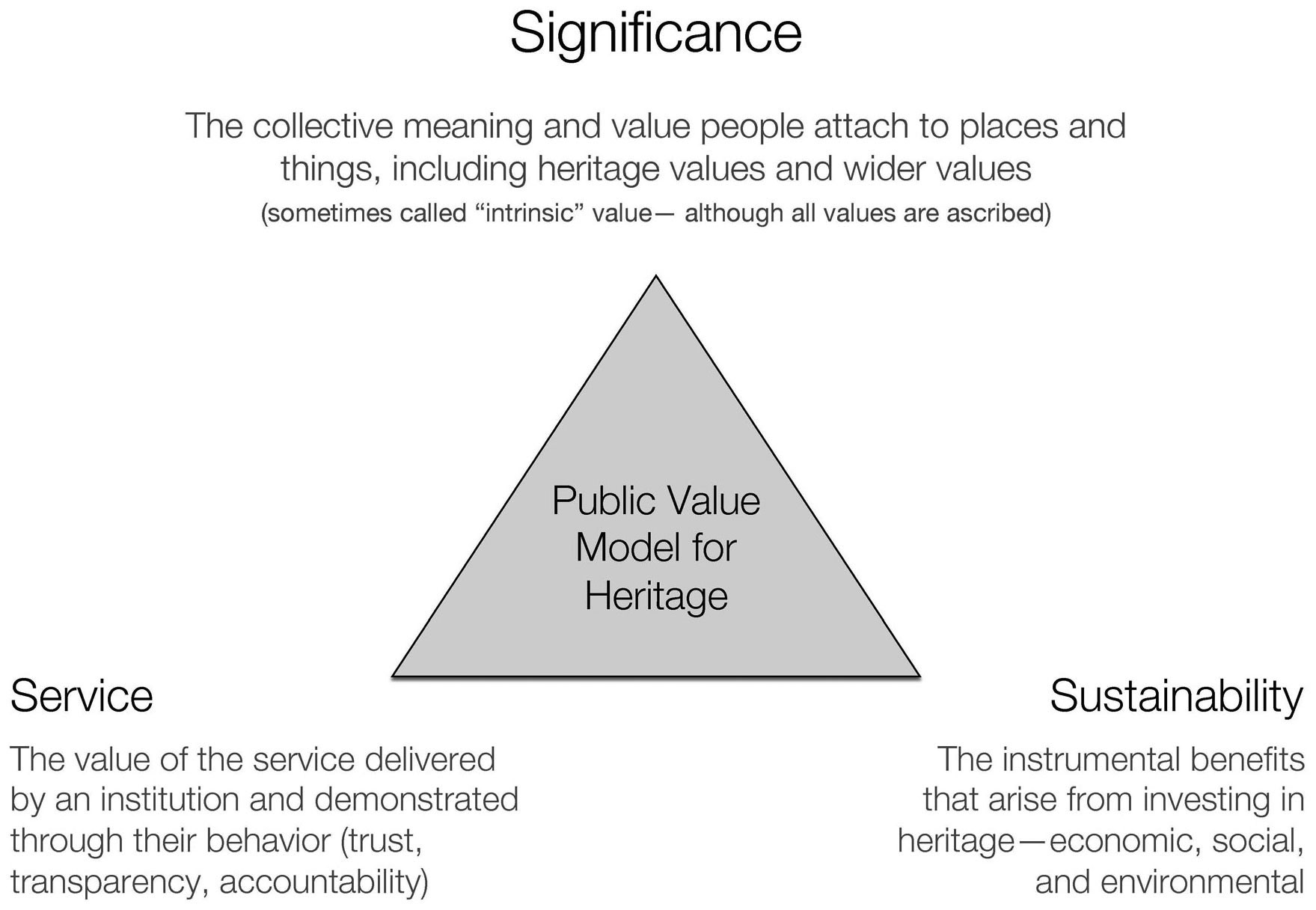

HLF commissioned Robert Hewison and John Holden () to devise a possible model. Hewison and Holden reviewed a range of different approaches to capturing the value of heritage. As well as looking at traditional measures of value, such as significance or the economic and social benefits of heritage, they also drew attention to Mark Moore’s work on public value. Moore () looks specifically at how public-sector organizations create value in the way they behave as organizations, including such qualities as trust, transparency, and accountability.

Hewison and Holden identified nine indicators for how HLF created value, encompassing three different kinds of value that in effect asked whether the fund was protecting what people cared about (significance, or “intrinsic” value); whether it was delivering wider economic, social, and other benefits (sustainability, or “instrumental” benefits); and whether it as an organization behaved in a manner that was trustworthy and accountable (through the service it provided to the public, or “institutional” values) (fig. 5.5). This took heritage values beyond a focus on what was achieved by protecting or investing in heritage sites and fabric to include values demonstrated through organizational behavior and the social process of conserving heritage (), an approach that was debated more widely at a conference in 2006 ().

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.5Since then, Hewison and Holden have taken this approach beyond HLF to show how understanding values plays a critical role in organizational strategies. Heritage organizations raise particular leadership challenges because they deal regularly with competing and often contradictory pressures. They are asked to be both more inclusive and attract a wider range of visitors, while also being more commercial, and to reconcile development and conservation, natural heritage and cultural heritage, collections and buildings. Because there are different views on what is important, passions run high and cultural heritage attracts a wide range of opinions on how it should be managed. For cultural heritage leaders, therefore, a clear sense of organizational values is as important as it is for other organizations, or perhaps even more so ().

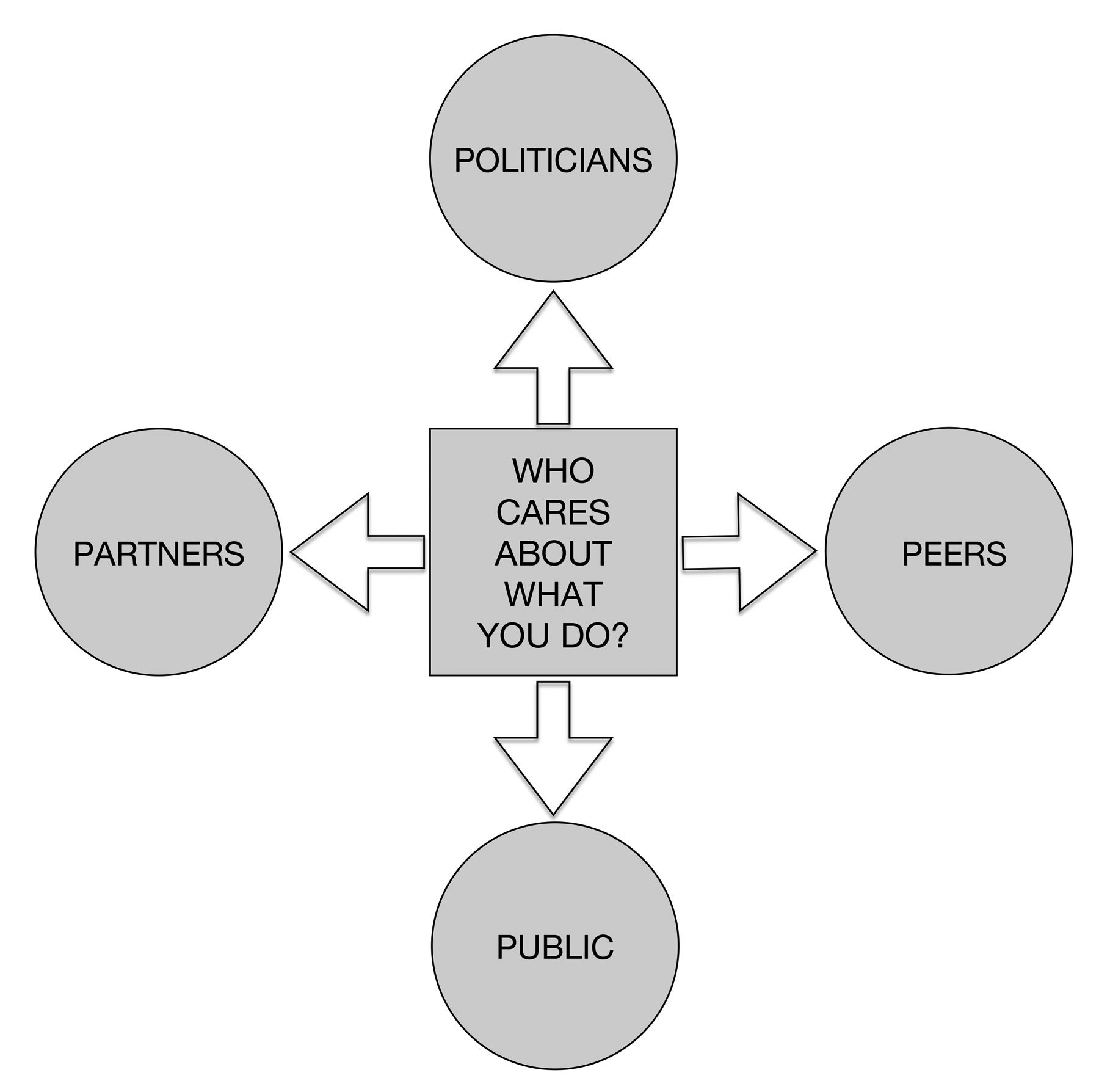

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6This is something Moore identifies in his work on public value: distinguishing different “audiences” for value, for instance looking at the difference between what the public might want of a cultural organization and what politicians might want. He describes these in terms of two key groups, “up the line” funders and politicians, and “down the line” customers and the public, and explores the different expectations each group might have (). For cultural heritage organizations the picture might more realistically be expanded to four groups of stakeholders: peers, partners, politicians (and funders), and the public (or customers) (fig. 5.6). Peers include people in similar organizations and within the sector; partners are the people an organization works with to deliver services; politicians or funders are the critical enablers who also provide legitimacy; and the public are the people who use or benefit from the service. Each group interacts with the cultural organization in a different way, and each has its own expectations.

Heritage leaders also need to recognize that these different stakeholders may have different priorities in terms of what they value. A funder may care about accountability, transparency, and delivery; a member of the public may value customer service; a partner may care about trust and collaboration; while a peer group may be more concerned with the quality of the heritage work. The political dimension is never far beneath the surface in any cultural organization, and leaders need to be acutely aware of the climate in which they operate and gain legitimacy. There is often more than one reporting line (for example to both a board of trustees and a government department), and multiple stakeholders, such as a separate foundation or membership organization. In order to maintain support and engagement, leaders need to be adept at recognizing those different audiences and what they care about without losing sight of the core purpose of the organization in the eyes of the public.

In constructing a model of value for a cultural heritage organization itself, therefore, it is important to think not just about the different kinds of value that the organization creates, but also the different “audiences” for that value. This is one of the issues that has emerged as part of the recent Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Cultural Value Project, which has been taking forward the wider values work in the UK through a series of commissioned pieces, including one on public value in organizations.8

Current Challenges

What does all of this mean for the values agenda today?

For heritage organizations at least, the question of how they create value through their services, practices, and behavior as organizations has never been more relevant. Leading a heritage organization today can feel as much about running a business as about delivering public services. This means that the ethics and values of heritage organizations themselves become even more challenging as they seek to maintain trust and engagement while also generating more income and becoming more businesslike. Demonstrating how an organization creates value for the wider public, at a time when public services have never been more under threat and in question, is perhaps the greatest and most interesting challenge for the values agenda. Equally, as Karina V. Korostelina demonstrates in her contribution to this volume, the ethical issues for individuals and organizations dealing with identity politics in and around heritage are huge and require enormous sensitivity and understanding.

In terms of sustainability—the economic, social, and environmental values of heritage—these questions are still as relevant, if not more so, as when the GCI values project first posed them. In a climate of austerity that questions the value of public services, the need is greater than ever to demonstrate the relevance of heritage to the wider economic, social, and environmental issues of our time. But in order to do that, we continue to need to generate good research about the value of heritage, using research techniques derived from social sciences, geography, economics, and other disciplines. The recent UK AHRC initiative around the value of culture has generated new interest in this field. There are stronger partnerships between academics and practitioners, and there is an emerging, albeit critical, research base.

In terms of the practical business of managing heritage sites, two decades after the launch of the GCI’s Research on the Values of Heritage project, the values-based approach is now fully part of the heritage practice toolbox. In the UK there is much more explicit thinking about values in wider heritage management and decision making. Applicants for funding at HLF are asked to explain what matters about their sites, and organizations such as the National Trust are rethinking their approach to value through a new emphasis on curatorship.

Despite that, there has been concern that the move toward thinking about values means a shift away from conserving fabric. Thinking about values should never displace the need for scientific investigation, core heritage craft skills, and good technical knowledge, but understanding different values helps to reconcile conflicts, manage sites, make difficult decisions, connect with different communities, and explore complexity in the process of managing heritage; the marriage of values and fabric will remain central for the field.

But understanding and working with values does more than that. Values are a common space that should bring together different specializations in heritage (ecology, history, design, buildings, museums, collections) and different community groups, recognizing that most heritage places are not buildings in isolation but mixtures of all of these. Values are also a powerful way to connect with different people and communities—understanding and respecting what is important to others brings people closer together, and heritage can be a powerful way to do that. The values-based approach is a critical way of embedding heritage in the wider world rather than seeing it as something separate.

Whether implicit or explicit, values will always be central to heritage practice. It is not a debate that will go away.

Notes

- See http://www.getty.edu/conservation/our_projects/field_projects/values/index.html/. ↩

- My use of the tripartite model of heritage value was inspired by the GCI values project where we debated the distinction between significance and the benefits of investing in heritage (intrinsic and instrumental values) (), and the model further developed in personal conversations with John Holden and Robert Hewison as part of the HLF review, which drew attention to Mark Moore’s work on public value (institutional values), discussed below. ↩

- In 2015 English Heritage was split into two organizations, Historic England (the public body that looks after England’s historic environment) and English Heritage (the registered charity that manages the National Heritage collection, comprising four hundred monuments in the care of the secretary of state). ↩

- For example, Glyndebourne produces community-based opera. See http://www.glyndebourne.com/education/about-glyndebourne-education/education-projects/commissions/hastings-spring-2/. ↩

- See article 6 of the Burra Charter () for a definition of the Burra Charter process. ↩

- The original HLF guidance has been replaced with a much shorter version online that separates values-based conservation plans from management and maintenance plans (). ↩

- See Anglo-Sikh Heritage Trail, http://asht.info/; and Hidden Now Heard, https://www.hlf.org.uk/our-work/hidden-now-heard. ↩

- See http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/research/fundedthemesandprogrammes/culturalvalueproject. ↩

References

- Amgueddfa Cymru / National Museum of Wales. 2017. “Llanmaes.” Portable Antiquities Scheme in Wales blog. Accessed July 30, 2017. https://museum.wales/portable-antiquities-scheme-in-wales-blog/.

- Australia ICOMOS. 2013. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. Burwood: Australia ICOMOS. http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf.

- Clark, Kate, ed. 1999. Conservation Plans in Action: Proceedings of the Oxford Conference. London: English Heritage.

- Clark, Kate, ed. 2006. Capturing the Public Value of Heritage: The Proceedings of the London Conference, 25–26 January 2006. Swindon, UK: English Heritage.

- de la Torre, Marta, Margaret G. H. MacLean, Randall Mason, and David Myers. 2005. Heritage Values in Site Management: Four Case Studies. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/values_site_mgmnt.

- Demos. 2004. Challenge and Change: HLF and Cultural Value: A Report to the Heritage Lottery Fund. London: Heritage Lottery Fund. https://www.hlf.org.uk/sites/default/files/media/research/challengeandchange_culturalvalue.pdf.

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport (London). 2001. The Historic Environment: A Force for Our Future. London: Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport (London). 2010. Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings: General Principles Applied by the Secretary of State When Deciding Whether a Building Is of Special Architectural or Historic Interest and Should Be Added to the List of Buildings Compiled under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. London: Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport (London). 2013. Scheduled Monuments and Nationally Important but Non-Scheduled Monuments. London: Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Accessed July 28, 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/249695/SM_policy_statement_10-2013__2_.pdf.

- English Heritage. 2002a. Heritage Dividend 2002: Measuring the Results of Heritage Regeneration 1999–2002. London: English Heritage.

- English Heritage. 2002b. State of the Historic Environment Report. London: English Heritage.

- English Heritage. 2008. Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance for the Sustainable Management of the Historic Environment. London: English Heritage. https://www.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/conservation-principles-sustainable-management-historic-environment/.

- English Heritage. 2011. English Heritage Corporate Plan 2011/2015. London: English Heritage. Accessed June 12, 2018. https://content.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/corporate-plan-2011-2015/eh-corporate-plan-2011-2015.pdf.

- English Heritage and Historic Environment Review Steering Group. 2000. Power of Place: The Future of the Historic Environment. London: Power of Place Office.

- Franklin, Geraint, and Historic England. 2017. Understanding Place: Historic Area Assessments. Accessed July 31, 2017. https://www.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/understanding-place-historic-area-assessments/.

- Heritage Lottery Fund. 2002. Broadening the Horizons of Heritage: The Heritage Lottery Fund Strategic Plan, 2002–2007. London: Heritage Lottery Fund.

- Heritage Lottery Fund. 2018. “Heritage Enterprise.” Website accessed June 11, 2018 (website reorganized after renaming of organization).

- Heritage Lottery Fund. n.d. Conservation Management Plans: Helping Your Application. Accessed June 19, 2018. https://www.academia.edu/3639647/Conservation_Management_Plans_-_Original_HLF_Guidance.

- Hewison, Robert, and John Holden. 2011. The Cultural Leadership Handbook: How to Run a Creative Organization. Aldershot, UK: Gower.

- Historic England. 2018. Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance. Accessed June 12, 2018. https://www.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/conservation-principles-sustainable-management-historic-environment/.

- Historic Environment Scotland. 2015. Conservation Principles for the Properties in the Care of Scottish Ministers. Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland. Accessed June 11, 2018. http://homedocbox.com/Landscaping/76836806-Historic-environment-scotland.html.

- Holden, John. 2006. Cultural Value and the Crises of Legitimacy. London: Demos.

- Kalman, Harold. 2014. Heritage Planning: Principles and Process. New York: Routledge.

- Kennet, Wayland. 1972. Preservation. London: Maurice Temple Smith.

- Moore, Mark H. 1995. Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Moore, Mark H., and Gaylen Williams Moore. 2005. Creating Public Value through State Arts Agencies. Minneapolis: Arts Midwest. Accessed June 19, 2018. http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/creating-public-value-through-state-arts-agencies.aspx.

- Morris, William. 1877. The Manifesto of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Accessed June 11, 2018. https://www.spab.org.uk/about-us/spab-manifesto.

- UK, Department of the Environment. 1990. Planning Policy Guidance 16: Archaeology and Planning. London: HMSO. Accessed October 1, 2017. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120906045433/http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/planningandbuilding/pdf/156777.pdf.

- UK, Department of the Environment and Department of National Heritage. 1994. Planning Policy Guidance 15: Planning and the Historic Environment. London: HMSO. Accessed October 1, 2017. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20060905135250/http://www.communities.gov.uk/staging/index.asp?id=1144041.

- UK Parliament. 1882. Ancient Monuments Protection Act, 1882, 45 & 46 Vict. Ch 73. Accessed June 11, 2018. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1882/73/pdfs/ukpga_18820073_en.pdf.

- UK Parliament. 1979. Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 c. 46. Accessed July 28, 2017. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1979/46/contents.

- UK Parliament. 1990. Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. Accessed August 1, 2018. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1990/9/pdfs/ukpga_19900009_en.pdf.

- US Government. 1906. The Antiquities Act of 1906. 16 USC 431–433. https://www.nps.gov/history/local-law/anti1906.htm.

- Welsh Assembly Government. 2011. Conservation Principles for the Sustainable Management of the Historic Environment in Wales. Cardiff, Wales: Cadw.

| words