12. Values and Relationships between Tangible and Intangible Dimensions of Heritage Places

- Ayesha Pamela Rogers

This essay investigates how the various values attributed to intangible aspects of cultural heritage places support their overall significance, including ways in which the values ascribed to both intangible and tangible dimensions of such places relate to each other. The tangible fabric of a place and the intangible aspects that give it meaning are inseparable. This relationship is not always coordinated or compatible, at times leading to creative or destructive tensions that have implications for values-based approaches to their conservation. Erica Avrami, Randall Mason, and Marta de la Torre suggest that “analytically, one can understand what values are at work by analyzing what stories are being told” (, 9). To frame thinking about these questions on values, I have selected five heritage places with which I have a long-term working relationship and have sought to identify the “stories being told” and the values at work.

I adopt a focused case study approach to investigate the social and physical histories of the places, acknowledging that values are “not fixed, but subjective and situational.”1 Specificity is required in order to reveal the complex and multidimensional values at work. The heritage places chosen are from Asian countries. They represent different periods and comprise built heritage, cultural landscapes, and living heritage places. The values and significance and their “stories” are revealed through a combination of cultural mapping providing the voice of communities, ethnographic tools representing the voice of heritage practitioners, historical research representing the voice of academics, and documentation reflecting the voice of the heritage itself.

These case studies should be read as short stories about intangible “public value,” which frames heritage as “a vital part of the public realm,” what Tessa Jowell defines as “those shared spaces and places that we hold in common and where we meet as equal citizens. The places that people instinctively recognize and value as not just being part of the landscape or townscape, but as actually being part of their own personal identity. That is the essential reason why people value heritage” (, 8). Each of the case study heritage places is briefly introduced and the different voices expressing different values are described, along with the resulting conflicts or tensions that characterize the place and the challenges arising from them. The final portion investigates what this means for a values-based approach to heritage conservation and management.

Tomb of Ali Mardan Khan, Lahore

This Mughal monument was built during the reign of Shahjahan (1628–58) by Ali Mardan Khan, a Persian nobleman who became governor of Lahore, Kashmir, and Kabul. He is famed as the architect and designer of the great canal that brought water from the River Ravi to Shalamar and the other gardens that gave Lahore fame as a “city of gardens.” The tomb was built for his mother, and he was later laid to rest beside her upon his death in 1656/57 (fig. 12.1).

Figure 12.1

Figure 12.1The building is an octagonal brick structure with lofty arched entrances on each side, topped with a massive dome on a tall drum. The corners of the roof are decorated with chattris (domed kiosks), and the whole building was originally adorned with tile mosaic and fresco work. It was once surrounded by a large geometric paradise garden (a form of garden of ancient Persian origin), and although most of it is now lost to encroachment, an original gateway remains at the northern side, richly embellished with colorful tile mosaics (). The impressive scale of the former garden compound can be gauged from the distance between the tomb and this extant gateway.

The contemporary uses of Ali Mardan Khan’s resting place, both authorized and unauthorized, illustrate the multiple values attributed to it by different communities. The tomb is officially protected and under the care of the provincial Department of Archaeology. There are no available statements of values or significance for such protected properties, but the aspects that receive recognition at this official level are usually antiquity, association with a historical figure, and/or aesthetic and architectural merit. The monument is formally closed to the public and therefore has virtually no value for most Lahoris, many of whom do not know of its existence. It is, however, open for religious observance on Thursday evenings when one form of living religious function is “authorized” for a specific community of users. Local devotees who view Ali Mardan Khan as a saint maintain his grave, located below the monument, cleaning, decorating, and providing electricity for weekly worshippers. This limited usage is tolerated in recognition of the important spiritual value of the heritage place to this community.

Another group also uses the tomb on Thursday evenings, but without the approval of the authorities. Female devotees climb to the hollow dome above the tomb to perambulate around their phir or religious leader, seeking fulfilment of their personal prayers in the dimly lit space. The weekly experience of the women gathering at the tomb is enhanced in intangible but pivotal ways by the setting. The intensely private interactions with a heritage space that we see in this narrative take on cultural complexity that would be lacking if they took place just anywhere. This use of the tomb represents “the expression of subaltern discourses on how people engage with history at intense and personal levels, achieved not by perceiving heritage through the filter of expert interpretation but by individual relationships with places and spaces” (, 118).

The Tomb of Ali Mardan Khan is a nationally protected monument. While the designation identifies the historical significance as “Mughal,” the determination of locals to enter and experience it has contributed to the continuous formation of new ideas about its values and significance. What we see is a clash between two ways of relating to the ancient material past. The first is an official modernist archaeology that identifies and circumscribes heritage sites—creating a heterotopia, or a place separate from the viewer’s daily reality (, 14)—and then presents them to the community only on its own terms. On the other hand we have a set of diverse, alternative popular approaches that project their own version of the heritage values of monuments, like the Tomb of Ali Mardan Khan, based on reconnecting such heritage places to daily life and contemporary needs.

The authorized heritage values associated with built heritage such as the Tomb of Ali Mardan Khan are based on architectural design and features, decorative aesthetics, age, and historical association. However, effective and relevant conservation also requires consideration of the meaningful contemporary uses of the building and its setting by groups that invest living values into the same built fabric. Currently, heritage properties in Pakistan such as this tomb are managed without reference to values or stakeholders. The result is a national landscape littered with historic places that are “preserved” but lifeless—sites of heterotopia (; , 14). The challenge is to find ways that values-based approaches can be introduced to change this kind of situation.

Historic Towns, Pakistan

The historic towns of Pakistan have never at any point in their history been planned or designed or, until very recently, conserved. The physical fabric and sense of place that has passed down to us has instead survived because of the desire of generations of residents to maintain their traditional way of life. Community cohesion or social capital has preserved what remains of the past and acts as a glue to ensure the continuing smooth functioning of the city, despite pressures of density, poor infrastructure, and social tensions. It is this intangible living heritage set within the built heritage of the city that gives significance to historic towns (fig. 12.2).

Figure 12.2

Figure 12.2The attributes of historic towns’ values illustrate this living, social nature of the city. These values are encoded in the links from private to increasingly public spaces in the built environment, interpersonal transactions, and the spatial patterns that position people and places within a mutually understood context ().

Study of the features and values of traditional neighborhoods and street markets shows that their real value does not reside in their historic appearance, heritage facades, or heritage craft products. It is in the sense of belonging and tradition that these places provide to different types of users—what is known as place attachment, or sense of place. Place attachment “is the symbolic relationship formed by people giving culturally shared emotional/affective meanings to a particular space of piece of land that provides the basis for the individual’s and group’s understanding of and relation to the environment” (, 165). This close interpersonal relationship is visible, for example, in the direct dialogue between shopper and shopkeeper, which takes place not inside a shop but at its entrance where shopkeepers sit (). These intangible values of knowledge, concepts, and skills can endure and link the ancient to the contemporary city in enriching and potentially profound ways.

The historic towns of Pakistan are a different kind of historic city, without landmark spaces or iconic heritage buildings, and not perceived as “heritage” at official levels, but beloved by their residents as physical embodiments of the traditional social capital that is their true heritage. The significance of such places rests in the densely packed areas of bazaars and mohollahs (neighborhoods), which have developed organically, creating an enduring and resilient pattern of urban life. The streets, buildings, and public spaces are imbued with societal values expressed by change, multiple uses and sensory experiences, traditions, and interpersonal relationships. These are beginning to come into conflict with the contemporary economic and development values that drive tourism as historic urban centers are increasingly exploited for their historic built environments, often at the cost of more intangible values.

In the historic towns of Pakistan and many other places around the world, there are few if any conservation projects being carried out because it is simply not yet part of most urban agendas. The rare examples of values-based conservation are “imported,” meaning that international organizations or foreign-trained experts have introduced their approach in isolated built heritage or urban upgrade projects. This has little lasting impact on local theory or practice. In such circumstances the challenge is not just to refine the effectiveness of values applications, but something much more fundamental—introduction of the basic concepts of values and their meaning and importance at the center of local heritage conservation.

Pak Mong Historic Village, Hong Kong

The historic villages of rural Hong Kong have evolved over the centuries from agricultural settlements into residential neighborhoods of the modern city (fig. 12.3). Many, such as the village of Pak Mong, retain the basic tangible elements of a southern Chinese traditional village dictated by and embedded in the ancient practice of feng shui.

Figure 12.3

Figure 12.3Feng shui, or kanyu as it is referred to in classical texts, is the ancient tradition of geomancy that embraces the “links between Chinese cosmology (heaven) and Chinese social reality (earth)” (, 1). By employing the five elements, four cardinal directions, and the concepts of yin and yang, feng shui shapes and designs the cultural landscape and its built elements both tangibly in terms of position, material, and form, and intangibly by channeling qi energy and forces to achieve balance between the cosmos, nature, and humanity.

Feng shui works at several different levels and endows a heritage place with multiple, complex values. The concept can position a settlement within the landscape to create a microcosmic environment that follows the dragons embedded in the mountains. It can order spatial relationships within this settlement to ensure the containment and beneficial flow of qi life force within the dragon’s xu (lair). It can also prescribe the architectural form of individual built elements and the best time for their construction to maintain balance and good fortune. Finally, nurturing of a feng shui woodland behind the village works to embrace the whole and ensures its continuity.

The persistence of the feng shui tradition is evident in the historic village of Pak Mong, founded more than six hundred years ago in the northeast of Lantau Island. The feng shui of Pak Mong has a yang line that is strong and derives straight from the distant mountain of Shek Uk Shan. To augment the yin, the path into Pak Mong has many bends and is surrounded by thick woods that prevent direct views to the exposed ocean. The feng shui wall was also built to prevent direct exposure of the village to the ocean. The “official” entryway is located at the far end of the village and is curved, again to prevent direct outflow.2

The wider setting of Pak Mong has been altered with the construction of a new airport and associated highway along the north of Lantau Island, and feng shui arrangements struggle to maintain the cosmic balance. The traditional feng shui layout is still visible in the village plan, although historic built features such as traditional green brick houses, shrines, an ancestral hall, and a watchtower are now overshadowed by modern three-story residences. It may appear that the tradition of geomancy has been lost and that the contemporary community values comfort and modernity over cosmic balance, but that would be incorrect.

Feng shui still looms large in the community psyche. Negative qi from the massive Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge being built to the north of the village has been linked by Pak Mong villagers to the death of eight residents since bridge construction commenced. The village is perceived as being between two of the bridges, an arrangement described in feng shui as like being between two swords. This conviction has led to protests, banners, and demands that the government pay for special ceremonies ten times every month until the bridge is completed to protect the village’s feng shui.

Intangible feng shui values do more than support the significance of historic villages like Pak Mong; they are, in fact, the primary source of that significance. As “the art of adapting the residences of the living and the dead so as to cooperate and harmonize with the local currents of the cosmic breath (or so called qi),” feng shui acts as the frame within which the traditional built environment can function (, 6). It guarantees security, longevity, and prosperity in the face of hostility and challenges from nature and the gods. The tangible aspects of Pak Mong, such as the traditional village layout, water bodies, shrines, ancestral hall, temple, and house rows, are enabled and validated by the intangible values of the geomantic landscape.

The multiple layers of intangible and tangible values associated with the village of Pak Mong present almost an opposite scenario to that seen in Pakistan’s historic towns; they are recognized and protected to varying degrees, but separately. The village itself is listed and a number of historical structures in it are graded within the Hong Kong heritage system. The feng shui woodland is listed under a forest and countryside ordinance, and feng shui features and concepts are considered by the heritage authorities to be essential parts of the urban and rural landscape to be included in management plans and impact assessments. So the issue is not lack of awareness of values embedded in multiple aspects of the place, but rather the division of these values into different categories under different jurisdictions. Can values-based conservation function in such situations?

Plain of Jars, Lao PDR

The mountainous province of Xieng Khouang in northern Lao PDR is home to the Plain of Jars, a series of at least eighty-five archaeological sites, each containing anywhere from one single jar carved from local stone to several hundred of them (fig. 12.4). The large monolithic jars date from the sixth century BCE to the fifth century CE, and excavations in 2016 revealed evidence of use of the area as a funerary landscape. While there has been knowledge of the site since research was first carried out in the 1930s, the culture that created this landscape is unknown and the Plain of Jars remains an enigmatic heritage place with multiple layers of values.

Figure 12.4

Figure 12.4For local inhabitants, the jars have mystical powers linked to tales of giant ancestors who used them for drinking vessels. Villagers use them for medicinal purposes and recycle jar fragments into contemporary burial markers. For them, the prehistoric archaeological landscape is imbued with intangible but powerful meaning. Its mystery has become a major tourism value. Tourism websites refer to secrets “lost in time,” emphasizing that “we still don’t know with any certainty who created the jars or why, and possibly we never will. The jars may hold on to their secrets forever” (, n.p.).

Another important layer of meaning, more tangible than the enigma, lies over the same rural landscape; this is the twentieth-century landscape of the Secret War (1964–73) as experienced by the contemporaneous local community (). During this period, the United States carried out approximately half a million bombing missions over Xieng Khouang. More than two million tons of ordinance were dropped, of which some 30 percent failed to detonate and remained on or below the surface of more than 25 percent of the province’s farmland, paddy fields, villages, and the Plain of Jars (). This unexploded ordinance (UXO) has implications for the safety of communities, accessibility of agricultural land, and development of tourism at the jar sites.

This is a landscape of devastation with modern negative and memorial values overlaying the ancient archaeological values, linked by tourism. These include the mystical value of the megalithic jars to local communities; economic value of mysterious archaeological remains and war tourism; archaeological and scientific research value of the jar sites; and memorial value of a landscape in which so much life was lost in living memory. It is not surprising that in the perception of local residents of the Plain of Jars, the modern layer of the palimpsest represents particularly urgent and relevant societal values.

The multiple intangible layers of valuation seen at the Plain of Jars—traditional use and meaning, archaeological value, memorial function, tourism narratives—create a tension between tangible and intangible aspects of the place. However, at the same time they are all connected by the very tangible existence of UXO across the landscape and face the threat of loss, physical injury, and death that it poses.

The Secret War left evidence across the Plain of Jars landscape that serves as a tangible reminder of a heritage of pain (). The war is part of living memory for many, and bombing craters, bullet-ridden stone jars, and UXO are a permanent reminder of loss and risk. Every family in the Plain of Jars has suffered injury or lost members to death by UXO, even decades after the end of hostilities. The challenge for values-based conservation and management of the heritage place is how to acknowledge its memorial values alongside archaeological, scientific, and other values, including traditional meanings for local residents and future economic values derived from archaeological tourism, battlefield tourism, and ecotourism. None of these values can be explored or developed until the UXO is cleared, illustrating how closely linked tangible and intangible aspects of the site have become. How heritage professionals deal with these realities in the aftermath of war and in preparation of the World Heritage nomination currently under way will have implications for other sites in post-conflict areas.

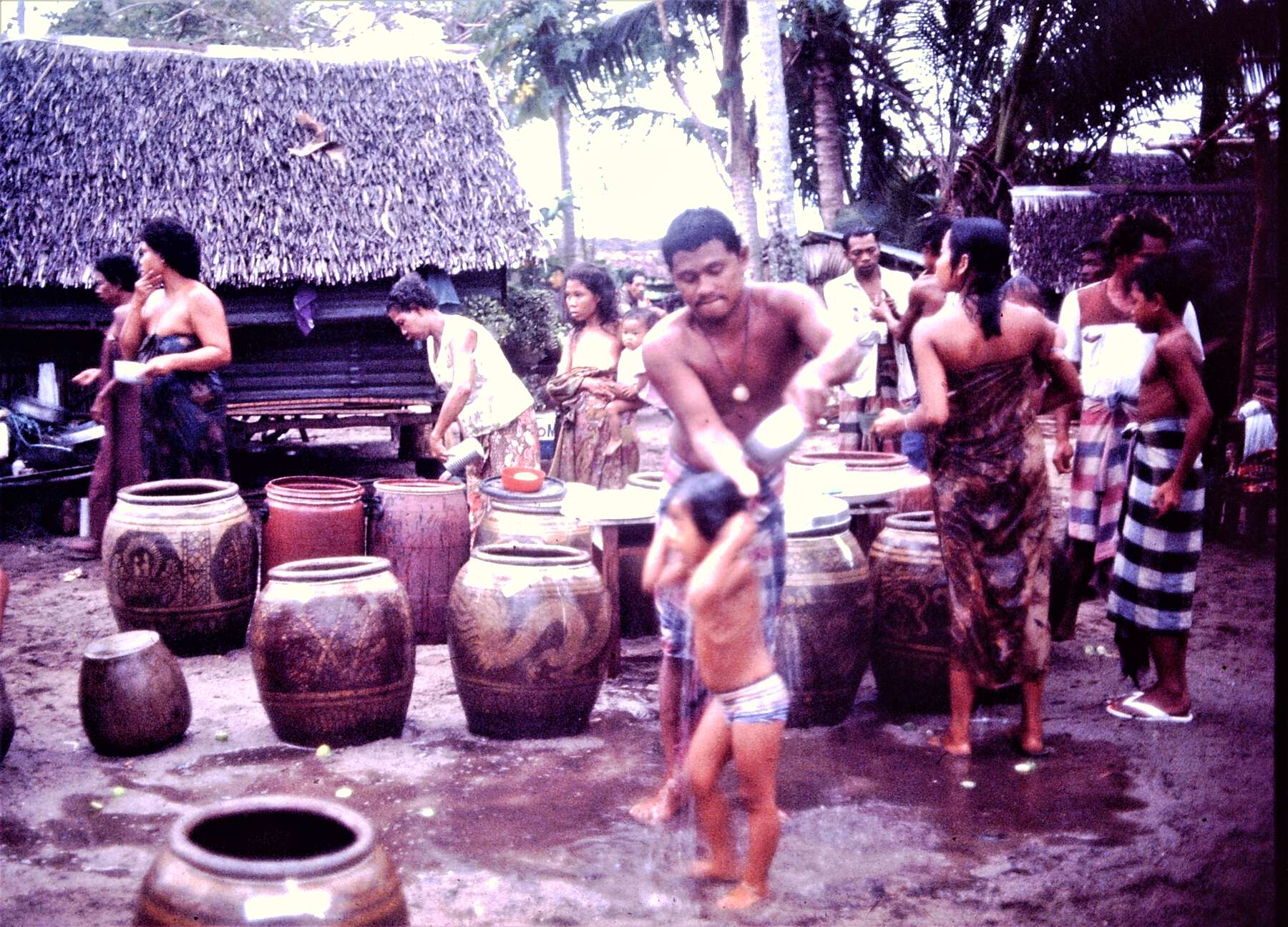

Maritime Adaptations of the Chaw Lay Sea Gypsies, Phuket, South Thailand

The Chaw Lay are an Indigenous population of the west coast of Thailand. Traditionally they live a nomadic existence over an area extending from Myanmar to Singapore. They travel from base settlements in Phuket and nearby islands to and from a wide range of fishing camps by small boats. This maritime adaptation results in minimal built environment features, for instance temporary structures, compacted sand surfaces, fires, and shell middens. Instead, values are reflected by the intangible and living heritage of the Chaw Lay on water and on shore: from birth to marriage and burial ceremonies; grave cleaning and feasting; Loy Rua, a days-long ceremony to mark the beginning and end of the monsoons and therefore access to the sea; the construction of ritual boats to carry evil out of the community; spirit houses for ancestors and carved poles to mark ceremonial areas; and song, chant, dance and magical potions to bring true love ().

All the adaptive flexibility that the Chaw Lay have built into their marine transhumance is reinforced, which is to say taught, through these annually repeated intangible practices that include the participation of far-flung groups and individuals and often even the ancestors. This can be seen in all types of intangible practice, from Loy Rua festivities to burial customs, where the point is to maintain linkages within the sea-based network of island sites, which, taken as a whole, is their home. In order to maintain this adaptation they value mobility—physical mobility, tool kit mobility, and social mobility. Seasonal ceremonies that bring together mobile groups serve as the cultural glue that fortifies the links between constantly moving Chaw Lay, tying children to the ancestors, facilitating courtship and marriage, and celebrating the people’s connection to their environment. These periodic intangible practices, which reinforce group solidarity, pass on the knowledge needed for a resilience strategy to counter cycles of fragmentation and dispersal (fig. 12.5).

Figure 12.5

Figure 12.5In other cultures, such practices are often ways to claim title over space, but this cannot be said for the Chaw Lay, whose entire adaptation is grounded in transience. Intangible practices can also be used to guarantee the right to exploit critical marine resources and reinforce group cohesion. These are not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, they are mutually inclusive, as together they provide stability and resilience in a mobile lifestyle.

The overall significance of Chaw Lay heritage resides almost exclusively in the multiple values attributed to their rich intangible culture. The concept of “heritage place” has limited meaning in such a mobile culture based on a perishable and small material culture. Chaw Lay heritage places are associated instead with specific ritual spaces, all conceptualized by the Chaw Lay in relation to the sea. These include the shoreline for launching ceremonial boats and posting poles and ancestral flags; hilltops overlooking the sea for ritual feasts; promontories and bays as locations for burial grounds; peripheral edges of villages as the site of spirit houses; and, critically, the surface of the sea itself as the ritual space for all of life.

For the Chaw Lay, heritage places are geographical locations in their physical environment and the values they attach to them are therefore mobile, abstract, and embedded in nature. The greatest threat facing the Chaw Lay and their cultural values is loss of these shorelines, promontories, bays, and marine resources to tourism, property development, and industrial fishing. This is happening now, and legal and overt conflict has arisen at Rawai, a heavily touristed beach in Phuket, where the Chaw Lay have been excluded from the entire range of their ecological niche. Rawai is a flash point, one of the last places where Chaw Lay values thrive, intangibly through the ceremonies and celebrations that take place there and tangibly in the nearby spirit area and cemetery. How does the values-based approach respond to such cases of imminent threat to Indigenous values from the modern world?

Discussion

Reflecting on these vignettes that focus on intangible and living values highlights issues for a values-based approach to heritage conservation and management. First, there are major challenges in places where values-based conservation is still not understood and has not been adopted. Large portions of the world’s heritage are in the custodianship of bodies who are unfamiliar with values concepts and values-based conservation approaches, and are actively suspicious of any stakeholder involvement. In these cases, all values, particularly social ones, play little or no role in the work of conserving and managing heritage places. This is particularly relevant in places such as Pakistan, which still follow the colonial code for heritage conservation prescribed in Sir John Marshall’s Conservation Manual: A Handbook for the Use of Archaeological Officers and Others Entrusted with the Care of Ancient Monuments (), where values are not part of decision making even at World Heritage properties. The narrow focus on the fabric of sites and monuments is reinforced by the legislative framework, which is similarly based on colonial-period heritage laws. There is little postcolonial discourse on heritage in Pakistan, surprisingly for a postindependence state trying “to continue a nineteenth-century vision of a nation in territories that were … made more divided as part of the process of European colonization” (, 266). There is widespread dissatisfaction with how heritage is dealt with, but at the same time a notable lack of postcolonial critique of official approaches to heritage management. Discussion of possible responses to this challenge are closely tied to my second point.

International values-based approaches are often applied to specific projects in countries where values do not usually play a role in heritage conservation. The aim is to introduce best practices, raise awareness of values-based conservation, and set new standards. However, in reality such efforts have no impact or lasting effect at the local level. For example, values-based principles may have guided management plans written for the Pakistan World Heritage properties of Lahore Fort and Shalamar Gardens, but it is fair to say that no conservation actions taken since, to implement these plans or manage heritage in general, have considered values in any way (; ). Setting examples of values-based best practice is not an effective way on its own to introduce and operationalize the approach in places without the appropriate value awareness framework. What is needed is focused capacity building to be embedded in existing university programs in heritage, architecture, and planning. Long-term investment in values training for government officers is needed for government officers in order to inform those already in decision-making positions and the younger generation of future officeholders.

Heritage conservators and managers need to acknowledge multiple and often conflicting layers of values at a place, particularly when they break down into traditional and Indigenous versus modernizing and global values. This is vividly enacted at all these heritage places. The way that local inhabitants of historic places have created social spaces within “inaccessible” monuments can enhance our understanding of how to conserve and manage the values of archaeological or built heritage. Similarly, core social values of community, communication, and sharing of activities and space in historic towns can be reflected in spatial plans and uses of heritage. A shift in focus to preserving patterns and relationships of such places over their appearance would preserve continuity of use and footprint while maintaining the spatial patterns that position people and places within a mutually understood context. Identification and understanding of intangible social values require wider use of anthropological and ethnographic skills and approaches combined with local participation and mapping of patterns, relationships, and interactions.

The strength of values-based conservation lies in great part in its recognition of the importance of stakeholder inclusion—bringing new groups into the values identification process in order to ensure more effective conservation planning with “responsiveness to the needs of stakeholders, communities, and contemporary society” (, 6). This lies at the core of identifying and understanding social values but is anathema for many heritage and antiquities departments in Asia and beyond. The challenge is to identify mechanisms for cooperation that bring multiple stakeholders into the process in ways that do not threaten authorities sensitive to criticism and change.

In Hong Kong, the village of Pak Mong illustrates how complicated this consideration of values can become; it is on the List of Recognised Villages, which includes villages proven to be in existence in 1898, reflecting value in age. A few historical buildings within such villages may be listed as graded buildings or monuments under the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance based on value in age, architectural merit, or rarity. Feng shui woodlands are protected either as Sites of Special Scientific Interest under the Forests and Countryside Ordinance or as conservation areas based on ecological and scientific value. Individual feng shui features inside and near historic villages and woodlands are inventoried for their historical and rarity value.

Thus Pak Mong represents values as seen through the expert eyes of forest and countryside officials, the antiquities department, planners, and researchers. Different sets of values that are not necessarily conflicting but embedded in different attributes are managed separately, often to the detriment of the values of the heritage as a whole. These disparate values can be merged if the village and its setting are viewed as a cultural landscape defined by and imbued with the intangible value of feng shui. Landscape is “the repository of intangible values and human meanings that nurture our very existence. This is why landscape and memory are inseparable because landscape is the nerve centre of our personal and collective memories” (, 4). In the case of the Chaw Lay, a cultural landscape framework could support the safeguarding of intangible values linking sea and islands, communities, and generations of people that are attached to places but not to tangible heritage built form.

The challenge for values-based conservation and management of the Plain of Jars is to balance memorial values alongside archaeological, scientific, and other values, including traditional meanings for local residents and future economic values derived from archaeological tourism, battlefield tourism, and ecotourism. The Lao-UNESCO Programme for Safeguarding the Plain of Jars (initiated in 1998) focused on locally led site documentation, UXO clearance to create a safe and stable environment, local community-based heritage and tourism management, and monitoring of socioeconomic and cultural impacts. This approach has been replaced by a new collaborative project between Lao and Australian researchers that hopes to “unlock more of the secrets behind the Plain of Jars.” The focus is on archaeological investigations, including excavation and “an array of advanced analytical techniques” involving experienced researchers and advanced technology and innovation from Australia (). This change in approach risks a change in how the landscape is valued. “While looking at the same vistas, locals often see ‘landscapes of continuity,’ which they adapt to present needs, whereas archaeologists often see ‘landscapes of clearance,’ created by taxonomies that have the impact of freezing the past and removing it from present use” (, 25).

Each of these case studies contributes to our understanding of how the values attributed to intangible aspects of cultural heritage places support their overall significance: the personal spiritual narratives of ordinary Lahorites add rich meaning to an otherwise undervalued and neglected Mughal monument; the living social values of Pakistan’s historic towns generate the sense of place fundamental to their significance; the significance of Pak Mong traditional village is based on adherence to intangible geomantic principles; at the Plain of Jars, we see an unexplained archaeological landscape overlain with intangible memorial values linked to all-too-tangible evidence of recent violence; and in Phuket intangible ceremonies, ritual space, and linkages over water combine to define the essence of the Chaw Lay adaptation.

These case studies also illustrate what Erica Avrami and Randall Mason describe in their essay in this volume as the problematic nature of values and value conflicts. As we recognize an increasing range of values ascribed by differing actors and delve into their multiplicity, mutability, and interrelationships, it becomes apparent that conserving them all may well be impossible; decisions must be made, priorities set. The aim of values-based conservation is to understand the variety and nature of values ascribed to a place and integrate that understanding into decision making that results in effective, relevant conservation. The challenge is how values-based approaches can achieve this and strengthen the kinds of value relationships described in the case studies presented above in ways that may create better outcomes for heritage conservation and management.

These value relationships highlight the importance of “social value,” described by Siân Jones as the value that “encompasses the significance of the historic environment to contemporary communities, including people’s sense of identity, belonging and place, as well as forms of memory and spiritual association. These are fluid, culturally specific forms of value created through experience and practice. Furthermore, whilst some align with authorized heritage discourses, others are created through unofficial and informal modes of engagement” (, 1). Recognition and development of these “informal modes of engagement” is key to successful integration of these important social values into values-based conservation. Avrami and Mason point out that there are always social values behind heritage, because heritage, as a means of connecting people and place through memory and narrative, is a social construction: “By redefining the social dimension of heritage beyond static statements of significance and toward dynamic processes of engagement with clear societal aims, the heritage field has the potential to serve as a powerful agent of change.”

Notes

- To quote Avrami and Mason in this volume. ↩

- Patrick Hase, personal conversation, 1997. ↩

References

- Australian Embassy. n.d. “Australia-Lao Plain of Jars Collaboration.” Australian Embassy Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Accessed July 3, 2017. http://laos.embassy.gov.au/vtan/AustLaoPlainofJars.html.

- Avrami, Erica C., Randall Mason, and Marta de la Torre. 2000. Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/values_heritage_research_report.

- Babcock, Daniel. 2017. “Northeast Laos and The Mysterious Plain of Jars: What You Need to Know.” Tripzilla, April 17, 2017. https://www.tripzilla.com/laos-plain-of-jars/57414.

- Batool, Zunera. 2017. “Analysing Appropriate Systems to Conserve Traditional Bazaars: Case Study of Lohari Gate Bazaar, Lahore.” MPhil thesis, National College of Arts, Lahore, Pakistan.

- Box, Paul. 2003. “Safeguarding the Plain of Jars: Megaliths and Unexploded Ordnance in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic.” Journal of GIS 1:92–102.

- Ding, Yuan. 2005. “Kanyu (Feng Shui): The Forgotten Perspective in the Understanding of Intangible Setting in China’s Heritage Sites.” In Monuments and Sites in Their Setting: Conserving Cultural Heritage in Changing Townscapes and Landscapes: Proceedings of the Scientific Symposium. ICOMOS 15th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium, Xi’an, China, 17–21 October 2005. Accessed December 15, 2017. https://www.icomos.org/xian2005/papers.htm.

- Foucault, Michel. 1984. “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias.” Translated by Jay Miskowie. Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, October 1984, reprinted at http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/foucault1.pdf.

- Harrison, Rodney, and Lotte Hughes. 2009. “Heritage, Colonialism and Postcolonialism.” In Understanding the Politics of Heritage, edited by Rodney Harrison, 234–69. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Jones, Siân. 2016. “Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities.” Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage 4 (1): 21–37.

- Jowell, Tessa. 2006. “From Consultation to Conversation: The Challenge of Better Places to Live.” In Capturing the Public Value of Heritage: The Proceedings of the London Conference 25–26 January 2006, edited by Kate Clark, 7–14. Swindon, UK: English Heritage.

- Khan, Rustam. 2017. “Management of Gujrat Walled City’s Heritage: A Case Study of Community’s Role in the Process.” PhD diss., National College of Arts, Lahore, Pakistan.

- Lari, Yasmeen. 2003. Lahore: Illustrated City Guide. Karachi: Heritage Foundation Pakistan.

- Logan, William, and Keir Reeves, eds. 2009. Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with “Difficult Heritage.” Key Issues in Cultural Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Low, Setha M. 1992. “Symbolic Ties That Bind: Place Attachment in the Plaza.” In Place Attachment, edited by Irwin Altman and Setha M. Low, 165–85. Human Behavior and Environment: Advances in Theory and Research 12. New York: Plenum.

- Marshall, John. 1923. Conservation Manual: A Handbook for the Use of Archaeological Officers and Others Entrusted with the Care of Ancient Monuments. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing India.

- Mason, Randall. 2002. “Assessing Values in Conservation Planning: Methodological Issues and Choices.” In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage: Research Report, edited by Marta de la Torre, 5–30. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. Accessed March 11, 2017. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/values_cultural_heritage.

- Rogers, Ayesha Pamela. 2011. “A Popular Past: Personal Narratives of Heritage Places.” Sohbet 2: Journal of Art & Culture 2, https://www.academia.edu/1248861/A_Popular_Past_Personal_Narratives_of_Heritage_Places.

- Rogers, Pamela. 1992. “Celebrations of the Sea People of Southern Thailand.” Hong Kong Anthropologist 5:29–32. http://arts.cuhk.edu.hk/~ant/hka/documents/oldseries/HKA05.pdf.

- Rogers, Pamela R., and Julie Van den Bergh. 2008. “The Legacy of a Secret War: Archaeological Research and Bomb Clearance in the Plain of Jars, Lao PDR.” In Interpreting Southeast Asia’s Past: Monument, Image, Text, edited by Elizabeth A. Bacus, Ian C. Glover, and Peter D. Sharrock, 400–408. Singapore: NUS.

- Skinner, Stephen. 1982. The Living Earth Manual of Feng Shui: Chinese Geomancy. New York: Arkana Penguin.

- Stroulia, Anna, and Susan Buck Sutton, eds. 2010. Archaeology in Situ: Sites, Archaeology, and Communities in Greece. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

- Taylor, Ken. 2008. “Landscape and Memory: Cultural Landscapes, Intangible Values and Some Thoughts on Asia.” In Finding the Spirit of Place: Between the Tangible and the Intangible: 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Scientific Symposium, 29 Sept–4 Oct 2008, Quebec. Accessed December 18, 2017. https://www.icomos.org/quebec2008/cd/toindex/77_pdf/77-wrVW-272.pdf.

- UNESCO Islamabad. 2006. Shalamar Gardens Master Plan 2006–2011. Islamabad, Pakistan: UNESCO. Accessed December 18, 2017. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002169/216928e.pdf.

- UNESCO Islamabad, Pamela Rogers, and Yasmeen Lari. 2006. Lahore Fort Master Plan 2006–2011. Islamabad, Pakistan: UNESCO. Accessed December 18, 2017. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002202/220201e.pdf.