10. Changing Concepts and Values in Natural Heritage Conservation: A View through IUCN and UNESCO Policies

- Josep-Maria Mallarach

- Bas Verschuuren

Our global ecological footprint surpasses Earth’s biocapacity by 35 percent and keeps growing (). Meanwhile, exponential economic growth continues to drive global climate change () and biodiversity extinction (). If these trends remain unabated, a global ecological collapse is probable (). The Western technocratic and materialistic paradigm, identified as one of the main drivers of these trends, requires urgent change that is not likely to be derived from the very same paradigm (). Simultaneously, these developments constitute a radically new context for conceiving, evaluating, and prioritizing heritage conservation policies.

New directions in natural heritage conservation are not just derived from bridging an abstract dichotomy between utilitarian or economic values and intangible cultural and spiritual values, but rather from acknowledging the conflicting relationships between societies and their environments. These relationships could be characterized as anywhere between healthy and harmonious to pathological and destructive for natural heritage conservation. New directions in natural heritage conservation increasingly emphasize the role of cultural values and subsequently seek common ground among shared values between different worldviews and knowledge systems.

The divide between nature and culture has been acknowledged as one of the foundational features of Western ontology that bedevil the realm of natural heritage conservation (). As a result, many countries created separate policies for natural and cultural heritage conservation, including different administrations that apply different legislation, methods, languages, scientific disciplines, and practices. In protected areas, proposed integrated approaches to bridge this divide—for example the creation of eco-museums where ethnology, anthropology, and conservation converge—have had a rather limited impact. The more recent introduction of cultural values and bio-cultural conservation approaches may offer new ways forward in bridging the nature-culture divide in natural heritage conservation (; ; ; ).

Below, we briefly describe the following shifts in heritage conservation within protected and conserved areas:

- from exclusive natural assessments to more holistic, natural-cultural approaches;

- from management to the inclusion of governance of natural heritage;

- from scientific expert valuation to valuation by Indigenous peoples, local communities, and other traditional knowledge holders;

- from tangible natural values to also including cultural, spiritual, and other intangible values;

- from applying top-down legal and regulatory frameworks to bottom-up rights-based approaches, including traditional laws, duties, and responsibilities.

Next, we describe how these changes have impacted the work developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and UNESCO using selected examples. We then look at some of their implications and applications at the national level in various countries around the world.

Changing Values and Concepts in Natural Heritage Conservation Policies

The 1999 publication Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity marked the onset of a new phase in conservation. Illustrated with examples from around the world, it argued that nature and culture are inextricably linked (, 1–18). Darrell Addison Posey’s conceptual framing of “cultural and spiritual” values had a significant impact on subsequent developments in international natural heritage conservation organizations such as UNESCO and the IUCN. The latter is the largest and most influential conservation organization in the world, including more than fourteen hundred government and nongovernmental organizations; some sixteen thousand scientists and experts participate on a voluntary basis, organized in numerous groups, under the umbrella of six commissions.

We recognize the following five changes to be essential to the process of changing values and concepts in natural heritage conservation:

From exclusive natural assessments to more holistic, natural-cultural approaches. During the second part of the twentieth century, most natural heritage assessments were validated using criteria based on Western natural sciences. This resulted in a number of new concepts and terminology, such as cultural landscapes (), bio-cultural diversity (; ), and socio-ecological resilience ().

From management to the inclusion of governance of natural heritage. Complementary to management, the complex concept of governance of natural heritage was developed during the twentieth century (). This led to the creation of the IUCN management and governance matrix, where categories of protected areas are cross-checked with four broad governance types, namely governance by government, shared governance, private governance, and governance by Indigenous peoples and local communities (). While this development has been quite an achievement, it has also received some critiques claiming that “the matrix” takes a narrow and restrictive view on governance () and excludes nonhuman agency while ignoring spiritual governance ().

Monastery Gregoriu, one of the twenty sovereign monasteries that constitute the Monastic Republic of Mount Athos, Greece, a natural and cultural World Heritage Site, which is ruled by a customary governance system that has been in place for more than a millennium. Figure 10.1

Figure 10.1Monastery Gregoriu, one of the twenty sovereign monasteries that constitute the Monastic Republic of Mount Athos, Greece, a natural and cultural World Heritage Site, which is ruled by a customary governance system that has been in place for more than a millennium. Image: Josep-Maria Mallarach The concept of governance encompasses who makes decisions, and the context of and procedures for how decisions are made. For example, traditional forms of governance are part of religious traditions at Mount Athos in Greece (fig. 10.1). It includes rights holders and stakeholders as well as legal instruments across different powers and levels of decision making. A notable innovation in the IUCN conceptualization of governance is that besides types, it includes quality and vitality. Governance quality includes, among other aspects, legitimacy and equity in relation to all actors involved in heritage conservation, including Indigenous peoples and local community conserved areas ().

From scientific expert valuation to valuation by Indigenous peoples and local communities and other traditional knowledge holders. Science-driven expert valuation has gradually opened up and given way to valuation by the keepers of traditional, religious, cultural, and spiritual values of natural heritage, such as Indigenous peoples, spiritual leaders, and local communities (). This has led to the recognition of values derived from traditional sciences, customary norms, religious and spiritual teachings, and traditional practices (), resulting in increased interest in shared values between Western scientific approaches and traditional sciences and worldviews within the interpretation, management, and governance of natural heritage ().

From tangible to intangible heritage, including religious and spiritual values. There has been a move beyond tangible cultural attributes toward acknowledging the significance of intangible cultural and spiritual heritage (; ; ; ; ). The spiritual significance of nature includes animistic and religious values and has been among the most influential drivers for nature conservation throughout history (; ; ). More than 85 percent of humanity adheres to some faith, and religious institutions are among the oldest and most influential organizations in the world (). Conservation organizations have gradually realized the need to increase social support for natural heritage conservation in collaboration with religious organizations (). This realization has opened an inquiry into conservation contributions from other cosmologies, worldviews, and religions in the application of bio-cultural initiatives and approaches to natural heritage conservation (; ).

From top-down legal and regulatory frameworks to bottom-up rights-based approaches, including traditional codes, duties, and responsibilities. Natural heritage that has been conserved by traditionally protected areas has often applied top-down regulatory frameworks. Working from the bottom up, rights-based approaches enable Indigenous peoples, local communities, and other actors to continue traditional practices and ways of life that have conserved nature for many generations (). This results in the increased recognition of cultural and spiritual values and the inclusion of traditional law and cultural practices in natural heritage conservation. Several types of nonbinding designations and actors benefit from this approach, such as Indigenous and community conserved areas and territories (ICCAs), and sacred natural sites (SNSs) with their custodian and guardian communities (; ). ICCAs encompass a variety of terrestrial or marine areas managed by Indigenous peoples and local communities—that is, one of the four governance types recognized by IUCN (). ICCAs may be recognized as protected areas or complement a country’s protected area system as different, but effective, ways of supporting conservation ().

ICCAs are recognized under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) as protected areas. They count toward the global Aichi Biodiversity Target 11, to have 17 percent of all terrestrial and 10 percent of all marine ecosystems under protection by 2020 (). Signatory states report annually on progress toward this target based on strategic biodiversity action plans. Sacred natural sites are natural places that are spiritually significant for people and communities (). Sacred natural sites have been recognized to exist throughout all the IUCN management categories and governance types (). Many are looked after by Indigenous peoples, local communities, and/or followers of institutionalized religions ().

Selected Changes in IUCN

IUCN periodically adopts resolutions and recommendations that are known to have worldwide influence, setting the global conservation agenda. They support the development of international and national environmental law, identify emerging issues in conservation, and promote specific actions on ecosystems, protected areas, and species. Since 1948 more than one thousand resolutions have been adopted by IUCN member organizations (, 3). This section outlines how the aforementioned changes have affected some of the IUCN’s policies and strategic directions, in particular within the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), the oldest of the six IUCN commissions. Our analysis focuses on the recommendations and resolutions adopted by IUCN’s General Assembly and IUCN’s Best Practice Guidelines Series, prepared by different groups of experts, which we consider the most seminal documents issued by IUCN (tables 1, 2).

Year | Resolution/ Recommendation Number | Title |

|---|---|---|

2003 | Rec. 13 | Integrating Cultural and Spiritual Values in the Strategies, Planning and Management of Protected Natural Areas |

2008 | Res. 038 | Recognition and Conservation of Sacred Natural Sites in Protected Areas |

2008 | Res. 4.056 | Rights-Based Approaches to Conservation |

2008 | Res. 4.052 | Implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples |

2008 | Res. 4.099 | Acknowledging the Need for Recognizing the Diversity of Concepts and Values of Nature |

2012 | Res. 147 | Supporting Custodian Protocols and Customary Laws of Sacred Natural Sites |

2012 | Res. 2012 | Respecting, Recognizing and Supporting Community Conserved Areas |

2012 | Res 5.094 | Respecting, Recognizing and Supporting Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories |

2012 | Res. 009 | Encouraging Collaboration with Faith Organizations |

2014 | n/a | The Promise of Sydney |

2016 | Res. 033 | Recognizing Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature in Protected and Conserved Areas |

2016 | Res. 064 | Strengthening Cross-Sector Partnerships to Recognize the Contributions of Nature to Health, Well-Being and Quality of Life |

Year | Resolution/ Recommendation Number | Title |

|---|---|---|

2003 | Rec. 13 | Integrating Cultural and Spiritual Values in the Strategies, Planning and Management of Protected Natural Areas |

2008 | Res. 038 | Recognition and Conservation of Sacred Natural Sites in Protected Areas |

2008 | Res. 4.056 | Rights-Based Approaches to Conservation |

2008 | Res. 4.052 | Implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples |

2008 | Res. 4.099 | Acknowledging the Need for Recognizing the Diversity of Concepts and Values of Nature |

2012 | Res. 147 | Supporting Custodian Protocols and Customary Laws of Sacred Natural Sites |

2012 | Res. 2012 | Respecting, Recognizing and Supporting Community Conserved Areas |

2012 | Res 5.094 | Respecting, Recognizing and Supporting Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories |

2012 | Res. 009 | Encouraging Collaboration with Faith Organizations |

2014 | n/a | The Promise of Sydney |

2016 | Res. 033 | Recognizing Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature in Protected and Conserved Areas |

2016 | Res. 064 | Strengthening Cross-Sector Partnerships to Recognize the Contributions of Nature to Health, Well-Being and Quality of Life |

Year Published | Best Practice Guideline number | Complete Title | Integration of Cultural and Spiritual Values |

|---|---|---|---|

2004 | 11 | Indigenous and Local Communities and Protected Areas: Towards Equity and Enhanced Conservation | F |

2006 | 12 | Forests and Protected Areas: Guidance on the Use of the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories | F |

2006 | 13 | Sustainable Financing of Protected Areas: A Global Review of Challenges and Options | L |

2006 | 14 | Evaluating Effectiveness: A Framework for Assessing Management Effectiveness of Protected Areas, 2nd ed. | P |

2007 | 15 | Identification and Gap Analysis of Key Biodiversity Areas: Targets for Comprehensive Protected Area Systems

| L |

2008 | 16 | Sacred Natural Sites: Guide for Managers of Protected Areas | F |

2011 | 17 | Protected Area Staff Training: Guidelines for Planning and Management | P |

2012 | 18 | Ecological Restoration for Protected Areas: Principles, Guidelines and Best Practices | F |

2012 | 19 | Guidelines for Applying the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories to Marine Protected Areas | F |

2013 | 20 | Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action | F |

2013 | 21 | Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories Including Best Practice Guidance on Recognizing Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Types | F |

2014 | 22 | Urban Protected Areas: Profiles and Best Practice Guidelines | P |

2015 | 23 | Transboundary Conservation: A Systematic and Integrated Approach | P |

2016 | 24 | Adapting to Climate Change: Guidance for Protected Area Managers and Planners | P |

2016 | 25 | Wilderness Protected Areas: Management Guidelines for IUCN Category 1b Protected Areas | F |

Year Published | Best Practice Guideline number | Complete Title | Integration of Cultural and Spiritual Values |

|---|---|---|---|

2004 | 11 | Indigenous and Local Communities and Protected Areas: Towards Equity and Enhanced Conservation | F |

2006 | 12 | Forests and Protected Areas: Guidance on the Use of the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories | F |

2006 | 13 | Sustainable Financing of Protected Areas: A Global Review of Challenges and Options | L |

2006 | 14 | Evaluating Effectiveness: A Framework for Assessing Management Effectiveness of Protected Areas, 2nd ed. | P |

2007 | 15 | Identification and Gap Analysis of Key Biodiversity Areas: Targets for Comprehensive Protected Area Systems

| L |

2008 | 16 | Sacred Natural Sites: Guide for Managers of Protected Areas | F |

2011 | 17 | Protected Area Staff Training: Guidelines for Planning and Management | P |

2012 | 18 | Ecological Restoration for Protected Areas: Principles, Guidelines and Best Practices | F |

2012 | 19 | Guidelines for Applying the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories to Marine Protected Areas | F |

2013 | 20 | Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action | F |

2013 | 21 | Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories Including Best Practice Guidance on Recognizing Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Types | F |

2014 | 22 | Urban Protected Areas: Profiles and Best Practice Guidelines | P |

2015 | 23 | Transboundary Conservation: A Systematic and Integrated Approach | P |

2016 | 24 | Adapting to Climate Change: Guidance for Protected Area Managers and Planners | P |

2016 | 25 | Wilderness Protected Areas: Management Guidelines for IUCN Category 1b Protected Areas | F |

Every ten years the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas organizes a world congress, which sets the agenda for protected areas and issues recommendations that aim to influence the policies of the member organizations. The Fifth IUCN World Parks Congress, which took place in Durban, South Africa, in 2003, marked a major value shift in natural heritage conservation (). For the first time a substantial delegation from the world’s Indigenous peoples devised an articulate criticism of Western approaches to nature conservation. This included both technical approaches and injustices that Indigenous peoples have been suffering as a result of the creation of modern protected areas, for instance national parks and wildlife reserves (). The Durban Accord defined a new approach for protected areas, integrating conservation goals with the interests of all affected people (). Cultural and spiritual values were included in many recommendations. In particular, Recommendation 13 was fully devoted to integrating cultural and spiritual values in the strategies, planning, and management of protected natural areas, including bold strategic requests (). These recommendations have had a significant impact on all the IUCN Guidelines published since (see table 2).

The IUCN-WCPA Specialist Group on Spiritual and Cultural Values of Protected Areas (CSVPA), which was founded in 1998 and drove much of the process behind the aforementioned changes at the World Parks Congress in 2003, initiated the preparation of guidelines for protected area managers on sacred natural sites, focusing on Indigenous peoples (). In 2005 the Delos Initiative, focusing on sacred natural sites in technologically developed countries, emerged from CSVPA (); the initiative has identified a collection of sacred natural sites as case studies (fig. 10.2). Since 2012 CSVPA developed a program of work on the cultural and spiritual significance of nature in the governance and management of protected and conserved areas, which is in the process of producing best-practice guidelines, a peer-reviewed volume (), and training modules ().

Figure 10.2

Figure 10.2The impact of the 2003 World Parks Congress and the subsequent IUCN policy changes (; ; ; ) are also reflected in the number and scope of international events on cultural and spiritual values and sacred natural sites in protected areas organized in Europe (table 3). These last changes are notable, considering that Europe was the cradle of positivism and materialism.

Cultural and Spiritual Values of Protected Areas | |

|---|---|

2008 | Communicating Values of Protected Areas, Germany |

2010 | I Conference Carpathian Network of Protected Areas, Romania |

2011 | Conference Europarc Federation, Germany |

2011 | Spiritual Values Protected Areas of Europe, Germany |

2013 | II Conference Carpathian Network of Protected Areas, Slovakia |

2015 | Conference Society of Conservation Biology, France |

2016 | BPG Cultural & Spiritual Significance of Nature, Germany |

2017 | BPG Cultural & Spiritual Significance of Nature, Germany

|

Sacred Natural Sites | |

|---|---|

2006 | Delos Initiative 1, Montserrat, Spain |

2007 | Delos Initiative 2, Ouranoupolis, Greece |

2010 | Delos Initiative 3, Aanaar/Inari, Lapland, Finland |

2010 | Symposium on Religious World Heritage Sites, Kiev, Ukraine |

2013 | Mount Athos, Thessaloniki, Greece |

2016 | Initiative of World Heritage Sites of Religious Interest, France |

2017 | Delos Initiative 4, Malta |

Cultural and Spiritual Values of Protected Areas | |

|---|---|

2008 | Communicating Values of Protected Areas, Germany |

2010 | I Conference Carpathian Network of Protected Areas, Romania |

2011 | Conference Europarc Federation, Germany |

2011 | Spiritual Values Protected Areas of Europe, Germany |

2013 | II Conference Carpathian Network of Protected Areas, Slovakia |

2015 | Conference Society of Conservation Biology, France |

2016 | BPG Cultural & Spiritual Significance of Nature, Germany |

2017 | BPG Cultural & Spiritual Significance of Nature, Germany

|

Sacred Natural Sites | |

|---|---|

2006 | Delos Initiative 1, Montserrat, Spain |

2007 | Delos Initiative 2, Ouranoupolis, Greece |

2010 | Delos Initiative 3, Aanaar/Inari, Lapland, Finland |

2010 | Symposium on Religious World Heritage Sites, Kiev, Ukraine |

2013 | Mount Athos, Thessaloniki, Greece |

2016 | Initiative of World Heritage Sites of Religious Interest, France |

2017 | Delos Initiative 4, Malta |

In 2008 IUCN renewed its definition of protected areas: “A clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated and managed through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long term conservation of nature, with associated ecosystem services and cultural values” (, 8). The detailed interpretation of each word of the definition clarified that conserving “associated cultural values” was part of the mission of protected areas, and that “other effective means” for conserving nature include, for instance, “recognized traditional rules under which community conserved areas operate” (, 8–9). IUCN protected area categories were also redefined, including the governance dimension, cultural values, and spiritual values, and in connection with them the recognition of sacred natural sites (). This work built on a consensus about the meaning of “conservation,” an umbrella concept that includes “preservation,” “protection,” “sustainable use,” and “restoration” ().

The new definition of protected areas opened the door for a complementary concept of “conserved areas,” a term borrowed from the Convention on Biological Diversity () referring to natural areas or landscapes conserved through other than legal means—including those conserved through cultural and/or spiritual values. A specific IUCN Task Force on Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures was established in 2015 to carry out the task of providing guidance on assessment and recognition of these areas by governments ().

During the subsequent IUCN General Assembly, several resolutions were adopted on sacred natural sites included in protected areas, on rights-based approaches to conservation, and on the need for recognizing the diversity of concepts and values of nature or encouraging collaboration with faith organizations, which prompted the creation in 2015 of the Specialist Group on Religion, Spirituality, Environmental Conservation, and Climate Justice within the IUCN Commission on Environmental, Economic, and Social Policy.

The Promise of Sydney summarized the main outcomes of the last World Parks Congress, 2014, on how to engage the hearts and minds of people and engender lifelong associations among physical, psychological, ecological, and spiritual well-being (). Building on this, the conclusions of the IUCN World Conservation Congress in 2016 (the first to have a high-level segment on religion and conservation) clearly stressed the importance of spirituality, religion, and culture, including the wisdom of Indigenous and traditional peoples, for nature conservation. This was expressed in Navigating Island Earth: The Hawai’i Commitments, which argues for the necessity of cultivating a “culture of conservation” that links “spirituality, religion, culture and conservation”:

The world’s rich diversity of cultures and faith traditions are a major source of our ethical values and provide insights into ways of valuing nature. The wisdom of indigenous traditions is of particular significance as we begin to re-learn how to live in communion with, rather than in dominance over, the natural world. (, 2)

Selected Changes in UNESCO

This section highlights changes regarding the integration of cultural and natural values within the work and policies of UNESCO since the 1970s.

The UNESCO Man and Biosphere Program (MAB), launched in 1971, focuses on creating learning sites for sustainable development. Its aim is to integrate cultural and biological diversity, especially the role of traditional knowledge in ecosystem management (). The MAB promotes equitable sharing of conservation benefits derived from managing ecosystems through economic development that is socially and culturally appropriate and environmentally sustainable. After four decades in operation, the current MAB Strategy 2015–25 and the Lima Declaration continue to direct its integrative approach to natural and cultural values ().

The Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage () recognizes cultural, mixed, and natural heritage sites. In 1992 it became the first international legal instrument to recognize significant interaction between humans and the environment as cultural landscapes ().

World Heritage Sites are nominated by states based on six cultural criteria, assessed by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), and four natural criteria, assessed by IUCN. Assessment of the cultural and natural criteria has been done independently following the convention’s Operational Guidelines. Only more recently have IUCN and ICOMOS worked together to connect their practices and find ways to link the natural and the cultural as well as the tangible and intangible values of heritage sites (). Some criteria, such as World Heritage Convention Criterion VII, “exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance,” have been specifically reviewed for their applicability in natural and cultural heritage ().

Globally, a large proportion of Natural World Heritage Sites include sacred natural sites (). Acknowledging this fact, UNESCO launched the Sacred Natural Sites and Cultural Landscapes Initiative in 2005. A few years later, to provide appropriate recognition of the religious value and the role of religious communities in the management of World Heritage Sites, UNESCO launched the Initiative on Heritage of Religious Interest. The initiative has been tasked with preparing guidance for the management of these World Heritage Sites (). It is expected that once this guidance has been adopted by UNESCO, States Parties will implement it on a voluntary basis, thereby improving the recognition and quality of both governance and management of the values and attributes of religious interest in World Heritage Sites.

The Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity () and the coming into force of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage () and the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions () provide the ideal context in international policy to rethink the role of intangible heritage of natural, cultural, and mixed World Heritage Sites. While all these conventions work independently, much could be gained from developing synergies that mutually reinforce the interconnectedness of tangible and intangible heritage.1

Several United Nations programs are aimed at bridging the gap between cultural and biological diversity and the integration of Indigenous knowledge. These are the program on Biocultural Diversity, in collaboration with the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the program on Biodiversity and Local and Indigenous Knowledge. As a programmatic approach enables conventions and UN institutions to collaborate successfully, the collaboration between actual conventions proves complicated.

Implications and Applications at the National Level

The programmatic and policy changes in IUCN and UNESCO have guided the integration of cultural and spiritual values along with rights-based approaches in the work of international and national organizations and governments. Despite resistance from some sectors, such as the extractive industries, agriculture, and fisheries, the cultural and spiritual values of natural heritage have gradually been acknowledged in many countries’ conservation policies, strategies, regulations, and initiatives. There has not been any global analysis of the extent of these changes. The following section offers several examples of their integration in regional transboundary conservation, in national conservation approaches, and in specific conservation programs.

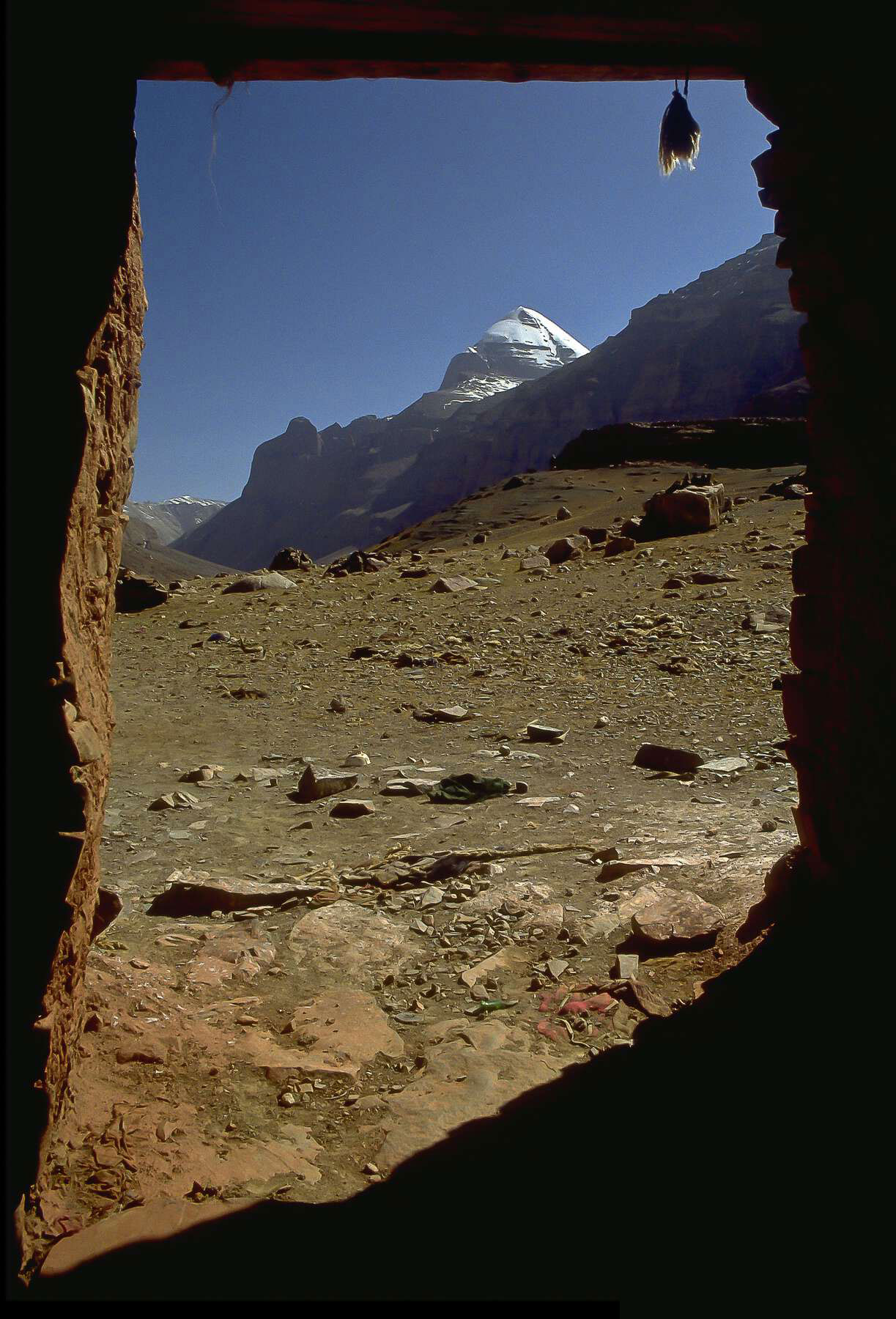

Inspired by the value changes discussed above, a number of transboundary ecosystem or landscape conservation initiatives, such as the Kailash Sacred Landscape Initiative, have integrated cultural and spiritual values in their work. The program, founded in 2009 by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMD), comprises a large area of Tibet and adjacent areas of Nepal and India. Mount Kailash is venerated by more than one billion Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Bön, and Sikh devotees, and has been a pilgrimage destination since prehistoric times (). The governments of the respective countries are currently exploring the possibilities of developing nominations for natural World Heritage Sites that would cover most of Kailash Sacred Landscape (fig. 10.3). The cultural and spiritual values of Kailash are guiding the preparation of the nomination files that describe the values for nomination of each part of the site.2

Figure 10.3

Figure 10.3An example of national-level integration of cultural and spiritual values is the development of a strategic direction on intangible heritage within the 2009–13 Action Plan for Protected Areas of Spain. This national-level action plan included a strategic direction on the development of a manual for protected-area managers to integrate cultural and spiritual values into their areas of responsibility (). The manual includes more than forty recommendations for incorporating intangible values into all stages of natural protected areas, governance, management, and planning. As a reference on the groundwork, it provides ten detailed case-study descriptions and more than one hundred examples of initiatives and experiences with the conservation of intangible heritage from Spain. For a summary see table 4, and for a more detailed explanation of the development and implementation of the manual see Mallarach et al. ().

Intangible Value | Examples |

|---|---|

Artistic | Traditional dance, music, songs, and rural games; nature painting and photography; nature literature; media, films, and television programs |

Aesthetic | Silence and tranquility; visual, auditory, and olfactory beauty; harmony |

Social | Traditional knowledge and trades; feasts and gastronomy; festivals and fairs |

Governance | Structures; rules; customs; traditional governance and institutions |

Historic | Relevant historical events and facts |

Linguistic | Languages and dialects; traditional legends and tales; sayings and riddles; vocabulary about nature and its meanings |

Religious | Rituals; pilgrimages; ceremonies; living shrines, monasteries, chapels, sanctuaries, and hermitages |

Spiritual | Sacred natural sites; abandoned shrines, temples, hermitages, etc.; archaeological sacred sites; other natural sacred sites |

Intangible Value | Examples |

|---|---|

Artistic | Traditional dance, music, songs, and rural games; nature painting and photography; nature literature; media, films, and television programs |

Aesthetic | Silence and tranquility; visual, auditory, and olfactory beauty; harmony |

Social | Traditional knowledge and trades; feasts and gastronomy; festivals and fairs |

Governance | Structures; rules; customs; traditional governance and institutions |

Historic | Relevant historical events and facts |

Linguistic | Languages and dialects; traditional legends and tales; sayings and riddles; vocabulary about nature and its meanings |

Religious | Rituals; pilgrimages; ceremonies; living shrines, monasteries, chapels, sanctuaries, and hermitages |

Spiritual | Sacred natural sites; abandoned shrines, temples, hermitages, etc.; archaeological sacred sites; other natural sacred sites |

In many countries across the world, cultural values such as beauty, silence, and tranquility are increasingly seen as significant and included in the development of new strategies for natural heritage conservation, permeating the national, regional, and local levels. Across Europe, national agencies responsible for natural heritage conservation have used such values to develop successful conservation tools, for instance the “Tranquility Areas” of England; the “Areas of Outstanding Beauty” in Scotland, England, and Wales; and the “Silence Areas” in the Netherlands. Silence and tranquility are considered human needs and the basic conditions for a deep connection with nature in cultures the world over.

Discussion and Conclusions

Natural heritage and cultural heritage cannot be considered in isolation. The evidence for interdependence and the relationships between humans and the environment justify new conceptualizations and the need to adopt integrated, coordinated approaches to the conservation of heritage ().

Many unsustainable global trends, such as climate change and biodiversity extinction, are affected by societal changes in positivistic, materialistic, and utilitarian values. We argue that slowing down the destruction of bio-cultural heritage requires implementing an array of new and integrated conservation approaches. However, to do away with the very root causes of these damaging value systems would require one to look beyond the practice of conservation and draw on fundamentally different philosophies that offer alternatives to materialism, neoliberalism, and capitalism (). From a philosophical and ethical perspective, we suggest seeking inspiration in the different cultural practices and worldviews of societies around the globe that have conserved natural heritage for millennia and have demonstrated their ability to adapt to the changes of time, as they provide valuable lessons (; ).

In the context of natural heritage conservation, we suggest a reassessment of the values of the last century’s conservation thinkers along with those enshrined in humanity’s great spiritual and religious traditions and those informing cultural practices and worldviews of Indigenous peoples and local communities. Such assessments would contribute to the gradual paradigm shift already under way in nature conservation (), based on the changes in concepts and values discussed in this article. Such assessment could also contribute to increasing commitment for adopting a conservation ethic as quoted in the previous section and proposed in the concluding remarks of the last IUCN General Assembly ().

Notes

References

- Apgar, Marina, Jamie M. Ataria, and Will J. Allen. 2011. “Managing beyond Designations: Supporting Endogenous Processes for Nurturing Biocultural Development.” International Journal of Heritage 17 (6): 37–41.

- Barnosky, Anthony D., Elizabeth A. Hadly, Jordi Bascompte, Eric L. Berlow, James H. Brown, Mikael Fortelius, Wayne M. Getz, John Harte, Alan Hastings, Pablo A. Marquet, Neo D. Martinez, Arne Mooers, Peter Roopnarine, Geerat Vermeij, John W. Williams, Rosemary Gillespie, Justin Kitzes, Charles Marshall, Nicholas Matzke, David P. Mindell, Eloy Revilla, and Adam B. Smith. 2012. “Approaching a State Shift in Earth’s Biosphere.” Nature 486:52–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature11018.

- Beltrán, Javier, ed. 2000. Indigenous and Traditional Peoples and Protected Areas: Principles, Guidelines and Case Studies. Best Practice World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), Protected Area Guidelines Series 4. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; Cambridge, UK: WWF International.

- Berkes, Fikret. 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis.

- Berkes, Fikret, and Carl Folke. 1998. Linking Social and Ecological Systems for Resilience and Sustainability. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bernbaum, Edwin. 2017. “The Spiritual and Cultural Significance of Nature: Inspiring Connections between People and Parks.” In Science, Conservation, and National Parks, edited by Steven R. Beissinger, David D. Ackerly, Holly Doremus, and Gary E. Machlis. 294–315. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Borrini-Feyerabend, Grazia, Nigel Dudley, Tilman Jaeger, Barbara Lassen, Neema Pathak Broome, Adrian Phillips, and Trevor Sandwith. 2013. Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series 20. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Bridgewater, Peter B., and Celia Bridgewater. 1999. “Cultural Landscapes, the Only Way for Sustainable Living.” In Nature and Culture in Landscape Ecology (Experiences for the 3rd Millennium), edited by Pavel Kovár, 37–45. Prague: Karolinum.

- Brosius, J. Peter. 2004. “Indigenous Peoples and Protected Areas at the World Parks Congress.” Conservation Biology 18 (3): 609–612. Accessed December 20, 2017. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.01834.x/full.

- Büscher, Bram, Robert Fletcher, Dan Brockington, Chris Sandbrook, William M. Adams, Lisa Campbell, Catherine Corson, Wolfram Dressler, Rosaleen Duffy, Noella Gray, George Holmes, Alice Kelly, Elizabeth Lunstrum, Maano Ramutsindela, and Kartik Shanker. 2016. “Half-Earth or Whole Earth? Radical Ideas for Conservation, and Their Implications.” Oryx 51 (3): 407–10.

- Campese, Jessica, Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend, Michelle de Cordova, Armelle Guigner, and Gonzalo Oviedo, eds. 2007. “Conservation and Human Rights,” special issue, Policy Matters 15.

- Convention on Biological Diversity. 1992. Accessed April 7, 2018. https://www.cbd.int/convention/.

- Convention on Biological Diversity. 2011. “Target 11.” In Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020, Including Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Montreal: Convention on Biological Diversity. Accessed April 7, 2018. https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/rationale/target-11/.

- Dearden, Philip, Michelle Bennett, and Jim Johnston. 2005. “Trends in Global Protected Area Governance, 1992–2002.” Environmental Management 36 (1): 89–100.

- Dudley, Nigel, ed. 2008. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Dudley, Nigel, Liza Higgins-Zogib, and Stephanie Mansourian. 2005. Beyond Belief: Linking Faiths and Protected Areas to Support Biodiversity Conservation. n.p.: World Wide Fund for Nature.

- Harmon, David. 2007. “A Bridge over the Chasm: Finding Ways to Achieve Integrated Natural and Cultural Heritage Conservation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 13 (4/5): 380–92. Accessed December 20, 2017. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13527250701351098.

- Harmon, David, and Allen D. Putney, eds. 2003. The Full Value of Parks: From Economics to the Intangible. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014. “Summary for Policymakers.” In AR5 Climate Change 2014. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, part A: “Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.” Edited by C. B. Field et al., 1–32. Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press. Accessed April 2018. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2003. Recommendations of the 5th World Parks Congress, 15–37. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2004. Durban Action Plan, IUCN World Parks Congress V. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. Accessed June 13, 2018. http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/durbanactionen.pdf.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2009. Resolutions and Recommendations: World Conservation Congress, Barcelona, 5–14 October 2008. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. Accessed June 13, 2018. https://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/wcc_4th_005_english.pdf.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2012. A Review of the Impact of IUCN Resolutions on International Conservation Efforts. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. accessed January 17, 2019. https://www.iucn.org/downloads/resolutions_eng_web.pdf.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2014. “The Promise of Sydney: World Parks Congress.” IUCN World Parks Congress 2014. Accessed June 18, 2018. http://www.worldparkscongress.org/about/promise_of_sydney.html.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2016. Navigating Island Earth: The Hawai’i Commitments. IUCN World Conservation Congress: Planet at the Crossroads, September 1–10, 2016, Hawai’i. Accessed December 20, 2017. https://portals.iucn.org/congress/hawaii-commitments.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature, United Nations Environmental Program, and World Wildlife Fund. 1980. World Conservation Strategy: Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Jonas, Harry D., Valentina Barbuto, Holly C. Jonas, Ashish Kothari, and Fred Nelson. 2014. “New Steps of Change: Looking Beyond Protected Areas to Consider Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures.” Parks 20 (2): 111–28.

- Kothari, Ashish, with Colleen Corrigan, Harry Jonas, Aurélie Neumann, and Holly Shrumm, eds. 2012. Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies. CBD Technical Series 6. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

- Latour, Bruno. 2011. “From Multiculturalism to Multinaturalism: What Rules of Method for the New Socio-Scientific Experiments?” Nature and Culture 6 (1): 1–17.

- Lee, Cathy, and Thomas Schaaf, eds. 2003. The Importance of Sacred Natural Sites for Biodiversity Conservation: Proceedings of the International Workshop Held in Kunming and Xishuangbanna Biosphere Reserve, Kunming and Xishuangbanna Biosphere Reserve, People’s Republic of China, 17–20 February 2003. Paris: UNESCO.

- Leitão, Leticia, and Tim Badman. 2015. “Opportunities for Integration of Cultural and Natural Heritage Perspectives under the World Heritage Convention: Towards Connected Practice.” In Conserving Cultural Landscapes: Challenges and New Directions, edited by Ken Taylor, Archer St. Clair, and Nora Mitchell, 75–92. Routledge Studies in Heritage. Oxfordshire, UK, and New York: Routledge.

- Lele, Sharachchandra, Peter Wilshusen, Dan Brockington, Reinmar Seidler, and Kamaljit Bawa. 2010. “Beyond Exclusion: Alternative Approaches to Biodiversity Conservation in the Developing Tropics.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2 (1/2): 94–100.

- Lockwood, Michael, Graeme L. Worboys, and Ashish Kothari, eds. 2006. Managing Protected Areas: A Global Guide. London: Earthscan.

- Loh, Jonathan, and David Harmon. 2005. “A Global Index of Biocultural Diversity.” Ecological Indicators 5:231–41.

- Maffi, Luisa, and Ellen Woodley. 2010. Biocultural Diversity Conservation: A Global Sourcebook. Abingdon, UK, and New York: Earthscan.

- Mallarach, Josep-Maria, ed. 2008. Protected Landscapes and Cultural and Spiritual Values. Values of Protected Landscapes and Seascapes Series 2. Heidelberg, Germany: Kasparek Verlag. http://data.iucn.org/dbtw-wpd/edocs/2008-055.pdf.

- Mallarach, Josep-Maria, ed. 2012. Spiritual Values of Protected Areas of Europe: Workshop Proceedings: Workshop Held from 2–6 November 2011 at the International Academy for Nature Conservation on the Isle of Vilm, Germany. BFN-Skripten 322. Bonn, Germany: Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN). https://www.bfn.de/fileadmin/MDB/documents/service/Skript322.pdf.

- Mallarach, Josep-Maria, Eulàlia Comas, and Alberto de Armas. 2012. El patrimonio inmaterial: Valores culturales y espirituales: Manual para su incorporación en las áreas protegidas. Manuales EUROPARC-España 10. Madrid: Fundación Fernando González Bernáldez. http://www.redeuroparc.org/system/files/shared/manual10.pdf.

- Mallarach, Josep-Maria, Marta Múgica, Alberto de Armas, and Eulália Comas. 2019. “Developing Guidelines for Integrating Cultural and Spiritual Values into the Protected Areas of Spain.” In Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature: Implications for the Governance and Management of Protected and Conserved Areas, edited by Bas Verschuuren and Steve Brown, 194–207. London: Routledge.

- Mallarach, Josep-Maria, and Thymio Papayannis, eds. 2007. Protected Areas and Spirituality. Proceedings of the First Workshop of the Delos Initiative, Monastery of Montserrat, Catalonia, Spain, 24–26 November 2006. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines. Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat; Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Martin, Gary J. 2012. “Playing the Matrix: The Fate of Biocultural Diversity in Community Governance and Management of Protected Areas.” In “Why Do We Value Diversity? Biocultural Diversity in a Global Context,” edited by Gary Martin, Diana Mincyte, and Ursula Münster, special issue, RCC Perspectives 9:59–64.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press. Accessed December 20, 2017. https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf.

- Mitchell, Nora, with contributions from L. Leitão, P. Migon, and S. Denyer. 2013. Study on the Application of Criterion (vii): Considering Superlative Natural Phenomena and Exceptional Natural Beauty within the World Heritage Convention. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. Accessed April 2018. http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/events/documents/event-992-14.pdf.

- O’Brien, Joanne, and Martin Palmer. 2007. The Atlas of Religions. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Palmer, Martin, and Victoria Finaly. 2003. Faith in Conservation. New Approaches to Religions and the Environment. Directions in Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Pandey, Abhimanyu, Rajan Kotru, and Nawraj Pradhan. 2016. “Kailash Sacred Landscape: Bridging Cultural Heritage, Conservation and Development through a Transboundary Landscape Approach.” In Asian Sacred Natural Sites: Philosophy and Practice in Protected Areas and Conservation, edited by Bas Verschuuren and Naoya Furuta, 145–58, London: Routledge.

- Papayannis, Thymio, and Josep-Maria Mallarach, eds. 2010. The Sacred Dimension of Protected Areas: Proceedings of the Second Workshop of the Delos Initiative, Ouranoupolis 2007. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; Athens: Med-INA.

- Phillips, Adrian. 2003. “Turning Ideas on Their Head: The New Paradigm for Protected Areas.” George Wright Forum 2:8–32.

- Posey, Darrell Addison, ed. 1999. Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity. London: Intermediate Technology.

- Pretty, Jules, Bill Adams, Fikret Berkes, Simone Ferreira de Athayde, Nigel Dudley, Eugene Hunn, Luisa Maffi, Kay Milton, David Rapport, Paul Robbins, Eleanor Sterling, Sue Stolton, Anna Tsing, Erin Vintinnerk, and Sarah Pilgrim. 2009. “The Intersections of Biological Diversity and Cultural Diversity: Towards Integration.” Conservation and Society 7 (2): 100–112.

- Pungetti, Gloria, Gonzalo Oviedo, and Della Hooke, eds. 2012. Sacred Species and Sites: Advances in Biocultural Conservation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rössler, Mechtild. 2005. “World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A Global Perspective.” In The Protected Landscape Approach: Linking Nature, Culture and Community, edited by Jessica Brown, Nora Mitchell and Michael Beresford, 37–46. Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. Accessed December 20, 2017. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2005-006.pdf.

- Schaaf, Thomas, and Cathy Lee, eds. 2006. Conserving Cultural and Biological Diversity: The Role of Sacred Natural Sites and Cultural Landscapes: International Symposium held at the United Nations University, Tokyo, 30 May–June 2005. Paris: UNESCO.

- Shackley, Myra. 2001. “Sacred World Heritage Sites: Balancing Meaning with Management.” Tourism Recreation Research 26 (1): 5–10.

- Stevens, Stan. 2014. “A New Protected Area Paradigm.” In Indigenous Peoples, National Parks, and Protected Areas: A New Paradigm Linking Conservation, Culture, and Rights, edited by Stan Stevens, 47–83. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- UNESCO [United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization]. 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Adopted by the General Conference at its Seventeenth Session Paris, 16 November 1972. Paris: UNESCO. Accessed April 2018. http://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf.

- UNESCO [United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization]. 1974. International Coordinating Council of the MAB Programme, Third Session; Washington, DC, 17–29 September 1974. Basis for a Plan to Implement MAB Project 8. Paris: UNESCO. Accessed June 18, 2018. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0001/000107/010720eb.pdf.

- UNESCO [United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization]. 2002. Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Cultural Diversity Series 1. Paris: UNESCO. Accessed April 2018. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001271/127162e.pdf.

- UNESCO [United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization]. 2003. “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Paris: UNESCO. Accessed April 2018. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001325/132540e.pdf.

- UNESCO [United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization]. 2005. The 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. Paris: UNESCO. Accessed April 2018. http://en.unesco.org/creativity/sites/creativity/files/passeport-convention2005-web2.pdf.

- UNESCO [United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization]. 2017. A New Roadmap for the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme and Its World Network of Biosphere Reserves. Paris: UNESCO. Accessed April 2018. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002474/247418E.pdf.

- UNESCO [United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization]. 2018. “UNESCO Initiative on Heritage of Religious Interest.” Accessed April 2018. https://whc.unesco.org/en/religious-sacred-heritage/.

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2012. Keeping Track of Our Changing Environment: From Rio to Rio+20 (1992–2012). Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme. Accessed December 20, 2017. http://www.grid.unep.ch/products/3_Reports/GEAS_KeepingTrack.pdf.

- Verschuuren, Bas. 2016. “Re-awakening the Power of Place.” In Asian Sacred Natural Sites: Philosophy and Practice in Protected Areas and Conservation, edited by Bas Verschuuren and Naoya Furuta, 1–14. London: Routledge.

- Verschuuren, Bas, and Steve Brown, eds. 2019. Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature in Protected Areas: Governance, Management, and Policy. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Verschuuren, Bas, Suneetha M. Subramanian, and Wim Hiemstra, eds. 2014. Community Well-Being in Biocultural Landscapes. Are We Living Well? Bourton on Dunsmore, UK: Practical Action.

- Verschuuren, Bas, Robert Wild, Jeffrey A. McNeeley, and Gonzalo Oviedo. 2010. Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture. London and Washington, DC: Earthscan.

- Wild, Robert, and Christopher McLeod, eds. 2008. Sacred Natural Sites: Guidelines for Protected Area Managers. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines 16. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; Paris: UNESCO. Accessed December 20, 2017. https://sacrednaturalsites.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/PAG-016.pdf.

- World Wildlife Fund. 2016. Living Planet Report 2016. Risk and Resilience in a New Era. Gland, Switzerland: WWF International.