2. Mapping the Issue of Values

- Erica Avrami

- Randall Mason

“Cultural heritage undergoes a continuous process of evolution.”

—“Nara + 20” (, 145)

What is the biggest challenge facing the heritage conservation field in the 2010s and beyond? The relevance of heritage and its conservation to contemporary society surely ranks high on anyone’s list. The basis of this chapter is the assertion that careful study of the role of values in conservation—how they are discerned, acted upon, reshaped by myriad actors—is essential to increasing the societal relevance of conservation.

Values have long played a central role in defining and directing conservation of built heritage. Value, wherever it resides, produces a flow of benefits. The dynamics among values and benefits are complex and tend toward conflict. One cannot maximize all values of a place; elevating one kind of value may come at a cost to others, and the weight given to different benefits is constantly changing. In nearly every aspect of conservation practice—from understanding and eliciting the values of heritage places to incorporating value assessments into decisions and policies—appraisals of value matter. Heritage professionals recognize that solving the puzzle of values is a central part of managing sites, determining treatments, deciding on tolerances for change, and ultimately serving society.

The particular roles played by values in conservation practice, and the range of values invoked as society constructs heritage, continue to evolve (). As the scope and scale of heritage conservation has grown, deeper complexities have emerged, many of them politically fraught. They emanate not simply from conservation professionals adopting new politics or looking at heritage places in new ways, but rather from myriad actors in society at large finding heritage useful and desirable. The politicization of heritage values is instigated by deep societal changes of the past few generations. It leaves us working in a field more open to external forces and more aware of our real and expected effects on lives and localities.

To operate effectively in the thoroughly politicized global society emergent in the last fifty years—in other words, to remain relevant and effective—conservation professionals have been challenged to broaden their perspective, enlist new partners, reframe inherited theories, and engage with political, economic, and cultural dynamics of the society writ large as part of the practice of conservation. Professionals, in other words, have been compelled to strengthen their traditional curatorial focus on a few, widely accepted categories of heritage value—historic, artistic, aesthetic, scientific—by sharpening their engagements with values activated by the broader societal processes affecting heritage (for instance the politicization of culture, the ubiquitous influence of economic thinking, changing governance models, the transformative effects of digital technology, and the role of the built environment and social-spatial dynamics in responding to climate change). Whether these broader societal forces shape decisions about built heritage for better or worse, it seems undeniable that conservation professionals must theorize and practice with them in mind.

This chapter creates a “map” of the overall subject of values as a practical, intellectual, and critical concept in conservation practice. It outlines relevant issues bridging practical, policy, and theoretical discourses in conservation, puts them in context of the field’s history, and explores the changing roles of values in contemporary conservation practice and policy. It gives particular emphasis to issues stemming from the validity of multiple value perspectives, the influence of larger societal forces shaping heritage values, decision-making tools and processes, the desire to evaluate and measure conservation outcomes, and the expert status of conservation professionals vis-à-vis other stakeholders and participants in conservation decisions.

The first part of this chapter introduces the subject and goals of the discussion. Then it moves on to look retrospectively at the evolution of value concepts in conservation, as well as in allied fields and social movements that have shaped conservation. It describes the conventional conservation concepts that manifest values thinking in practice, then outlines emergent trends and topics that mark recent debates over the effects of values in conservation. It takes stock of the current state of thinking and practice regarding values in conservation, while identifying problematic areas of practice as future research topics, then concludes with a brief summary of the implications of this research.

The Promise and Problem of Values

A single theme links all aspects of values-based conservation: the belief that conservation is more effective and relevant when the variety of values at stake for a place are well understood and embraced in decision making at all levels.

Concepts of “value” vary greatly in the parlance of different professional domains. Our use of the word requires clear definition at the outset. In the context of conservation, values refer to the different qualities, characteristics, meanings, perceptions, or associations ascribed to the things we wish to conserve—buildings, objects, sites, landscapes, settlements.1 Values are central to conservation decision making, though they are not the only factor to be accounted for.2 Values are not fixed, but subjective and situational. It follows that values must be understood in relation to the person or group ascribing a value to a place, and in relation to the place’s physical and social histories. Values are not always “good” qualities; they can also represent undesirable views or actors.

The trend of the last generation has been broadening the field’s ability to recognize, discern, document, and act on the dynamism of values—and indeed a broader range of values than admitted in traditional practice. The force behind this trend, we argue, came from broader societal forces more than factors internal to the field. Yet while conservation has embraced values-centered thinking and its attendant challenges—shifts in the literature of the field suggest this strongly—the response has been diligent, but not consistent.

People ascribe value to heritage in myriad ways, as there are often differences in how heritage professionals and the public at large find meaning in particular places. The contemporary conservation field is characterized by two distinct, complementary perspectives on values: one centered on heritage values, the other on societal values. The conservation field is rooted in heritage values, the core historic, artistic, aesthetic, and scientific qualities and narratives that form the basis for the very existence of the heritage conservation field. This perspective serves the core functions of heritage in modern society—sustaining historical knowledge, representing the past, memorialization—and is associated with the well-known curatorial, materialist traditions of conservation practice. A more contemporary, outward-looking perspective of societal values focuses on uses and functions of heritage places generated by a broad range of society-wide processes external to conservation. The societal-value perspective foregrounds broader forces forming the contexts of heritage places as well as the non-heritage functions of heritage places—including economic development, political conflict and reconciliation, social justice and civil rights issues, or environmental degradation and conservation.

The distinctions between heritage- and societal-value perspectives should not be overemphasized, yet they have become more salient against the societal developments of the last couple of generations. As different factions within societies assert their needs, heritage increasingly becomes useful for a broader range of reasons (as heritage per se, and beyond heritage). We emphasize this distinction between the two valuing perspectives neither to discredit traditional conservation practice and its pursuit of heritage values (although the hegemony of omniscient expertise needs to be challenged) nor to lionize critical theorists who advocate a radical shift toward societal values (and who appear rather too consumed with the politics and theorization of heritage to connect with practices of conservation). The ultimate goal here is acknowledging the difficult issues raised by the embrace of values-based ideas in their varied forms and for varied purposes, and enabling the flourishing of many constructive, critical, and practical perspectives on heritage and its conservation.

Other analysts () have observed this distinction in categories and deployment of values in practice, amounting to a discernment between essential and instrumental values—paralleling categories of heritage and societal values (a theme taken up in more detail later in this chapter).3 Heritage values tend to be treated as essential: they are the core concern of most conservation activities and are largely contingent upon protection of form and fabric. Societal values are regarded as instrumental in that they are intended to produce other, non-conservation outcomes. While heritage laws and government policies often cite societal values as part of their rationale for public investment—from education to economic benefit—there is often a disconnect between these broader aims and place-based practice.

As elaborated below, the ambition of the conservation field has traditionally been limited to essential values, and conflicts between essential and instrumental uses are common (see sidebar: “Displace, Destroy, or Defend?”). However, essential and instrumental uses can be complementary and cumulative, not exclusive. Both types of value and valuing perspectives are at play in most heritage places, most of the time. The conservation profession tends to magnify and segregate heritage values (and places bearing them) in order to protect them from the broad churn of social change. Because the societal uses of heritage are not completely aligned with conservation philosophy, tensions can arise, often changing the balance of decision making, deprioritizing traditional heritage values and vexing the profession.

While the intent of the heritage professional may be to preserve both heritage and societal values, the two perspectives differ in how they frame outcomes: the heritage-value perspective tends to regard material conservation and careful curation of heritage places as an end in itself, with social benefits and outcomes implied; the societal-value perspective regards heritage and its conservation as a means to a variety of social ends (economic gain, social justice, et cetera; see sidebar: “Societal versus Heritage Values”).

The two perspectives also differ in how values are conceptualized: the heritage-value perspective centers on the categorical importance of historic, artistic, aesthetic, and scientific values associated with heritage places as interpreted by experts and scholars; the societal perspective places more emphasis on the dynamic, complex interplay of heritage and societal values as activated by a wide variety of actors, interest groups, and institutions, including but extending well beyond the heritage conservation field. The challenge of contemporary conservation theory is weaving together both perspectives. Values discourse provides a basis for this.

The coexistence and conflict between these two perspectives is the main narrative of the last fifty years of conservation’s evolution. The turn toward a new paradigm counterposing these values perspectives stemmed from the deep political changes in the 1960s (as elaborated below). Since this time, the effects of different value perspectives are evident in myriad challenges to dominant, inherited power structures, while cultural diversity has been advocated ever more widely. In this milieu, heritage conservation got repositioned in relation to civil society: heritage became thoroughly politicized; heritage conservation became a ubiquitous, mass concern of global scale; conservation also took on a dual life as both state institution and protest movement, deployed variously to critique development and enable redevelopment; and the cultural interpretations and design decisions on which conservation stands became widely contested.

History and Evolution of Values and Valorization in Conservation

The embrace of value types as a foundational issue in heritage conservation by Alois Riegl, Camillo Boito, Gustavo Giovannoni, and other early European theorist-practitioners grew out of earlier cultural traditions of scholarship and connoisseurship (; ). These were amplified by modernity’s impulse to separate, sort, classify, and problem solve all kinds of complex phenomena. The point of such axiological work should not be interpreted as establishing absolute types, but rather as about discerning conservation values in relation to societal values at large with the goal of providing clear bases for decision making. Indeed, Riegl’s famous 1903 essay “The Modern Cult of Monuments” was part of a report on Austrian government heritage policy ().

Though the notion of heritage is ancient and has roots far beyond Europe, this chapter puts European conservation at the center of conservation historiography, acknowledging that, first, modernity created the need for a distinct concept of built heritage and conservation in the nineteenth century, and, second, modernity arose most forcefully from European experience, though it has ceased to be a purely Western concept. Fueled by globalization, modernity has been made “indigenous” by cultures across the world (; ).

Theoretical Foundations and the Curatorial Paradigm

The notion of heritage expertise and professionals tasked with the care of material heritage—the figure of the conservation expert—is built around certain conceptions of value and experts’ authority to understand and deal with it. The traditional heart of professional conservation practice is a curatorial paradigm based on the notion of a monument as bearer of heritage values—monuments are conceived as material objects, set aside from the usual social relations of typical or useful objects because of their extraordinary cultural value(s), requiring knowledgeable care and interpretation to fix their physical state and their meaning.4 The figure of the curator is imbued with expertise—in art history, design, and material science—to discern what heritage warrants collection and protection, and how to protect and interpret it. The establishment of conservation as a modern profession depended on the expert curator-conservator. While curation of monuments existed from antiquity, in the sense that artifacts and buildings possessing great age or association with important narratives warrant special placement and treatment (for instance in an urban square, or in a museum), the practice expanded greatly post-Enlightenment to encompass both found monuments and made monuments.5

The Post–World War II Age of Expertise and Internationalism

The heritage conservation field was transformed in the postwar decades by internationalization and institutionalization. Conservation institutions certainly existed in many countries well before the mid-twentieth century, formed in the nineteenth-century period of modernization in which heritage first claimed status as a contested public good to be routinely provided by governments, not only in Europe and its colonies, but also in the United States, Japan, and elsewhere. The desire to consolidate heritage conservation discourse internationally was realized in the Athens Charter of 1931 (). These efforts were organized internally (among experts). The drivers of postwar change to the conservation field were external: vast swings in economic fortune (booms and busts between and after the two world wars); the violence, destruction, and reconstruction caused by nearly global warfare; and, later, mass tourism.

The founding of UNESCO in 1945 elevated culture to the platform of international human rights, and built heritage was an important arena. Many nation-states improved or extended the legal bases of conservation. This internationalization of practice, methodology, and expertise was well represented in the creation of ICCROM (1959) and ICOMOS (1965) and the adoption of the Venice Charter in 1964 (). It was also represented generally in the elevation of the Italian mode of conservation, which is premised on sensitivity to heritage values, imbued with strong design and artistic sensibilities, and committed to applying scientific methods to conservation. The embrace of scientific epistemology as part of heritage conservation expertise was another transformative force in the profession, deepening conservation’s commitment to core heritage values and curatorial authority.

Acknowledgment of conservation expertise and the global reach of conservation issues paved the way for the contentious politicization of heritage in the 1960s and after by establishing heritage conservation among the routine public goods every society came to expect and utilize for varied political purposes. In other words, the bureaucratization of conservation in many governmental and other institutional forms (trusts, museums, conservancies) begat the other life of conservation in this period: as a visible protest movement.

Political Revolutions of the 1960s

The period around the 1960s marked a watershed moment of truly global dimension—political movements questioned sources of authority at every scale, in every field and discipline, on every continent. The results included an acute awareness of social injustice, acknowledgment of globalization, and the broad and deep politicization of culture. This was the culmination of developments beginning in the immediate postwar period: independence movements in colonies of the Global South; assertion of the civil rights of minority and subaltern groups within and across nation-states; and poststructuralism and postmodernism, broad intellectual movements challenging conventional ways of understanding how power and knowledge are deeply intertwined. Critiques were aimed at institutions, experts and expertise, top-down decision making, and metanarratives in general, opening conflicts over control of cultural identities, government agencies, and built environments.

Heritage conservation was deeply affected. “The initial 1960s–70s move toward radical democratization of the Conservation Movement was bound up with a revulsion against professionalism and experts in general” (, 325). Canonical ways of determining significance and claiming authority were challenged, resulting in the strong assertion of bottom-up decision making as well as the recognition of alternative interpretations of history and their reflection in built heritage. By the 1960s, protest was regarded as a central mode of conservation, set against the destructive forces of urban renewal, challenging colonial and nationalistic narratives and asserting the authority of minority cultures.

The 1960s set the heritage conservation field on a search for new methods and newfound relevance for the fragmented, contentious societal identities that emerged from empowerment politics. Conceptual underpinnings, sources of authority, and value discourses of conservation were also profoundly transformed in this era, constituting the “values turn” toward a greater embrace of societal perspectives alongside the heritage-values perspective. Political movements notably reshaped and strengthened core concepts, acknowledging multiple notions of authenticity and plural conceptions of significance. In both theory and practice, societal values have provoked innovative thinking while exposing frictions embedded in legal and public policy instruments.

Government institutions and NGOs began to shift in response, acknowledging the interests of minority and subaltern groups, devising consultation and decision-making models enabling the participation of broader publics, and adopting greater decision-making transparency and stakeholder engagement as key ethical and political strategies. The legacy of the 1960s for the conservation field was the embrace of new perspectives on value—foregrounding societal values related to contemporary uses, identities, and interests, while reframing devotion to long-standing historic and artistic (heritage) values.

The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, or Burra Charter () and the Nara Document on Authenticity () are key representations of the accumulated effects of the politicization of heritage conservation. This is clear, for instance, in the Burra Charter’s use of “cultural significance” emanating from grassroots practice. Burra addresses processes for appraising values and embraces a broader spectrum of heritage values (extending to the social and intangible). By calling for recursive reconsideration of cultural significance of heritage sites, the Burra Charter also acknowledges the situational nature of value appraisals and embraces the constructive tension within decision-making processes by incorporating participation and consultation of nonexperts in a process managed by experts and professionals.6

Burra’s focused response to cultural diversity, participation, and the notion of alternative authenticities (of Indigenous cultures vis-à-vis Anglo-Western culture) inspired the field and contributed to a period of experimentation with more participatory models used in allied design and environmental fields such as architecture, city planning, rural development, and environmental conservation. Democratization of conservation practice took hold in other contexts as well, including advocacy planning in the 1960s, the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Main Street Program (rebranded Main Street America in 2015), and Parks Canada’s commemorative integrity practices.

International charters and national laws are probably slowest to respond to changing value perspectives. For example, the Venice Charter, US and Canadian national preservation policies, and UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention support more or less fixed conceptions of significance based on a narrow spectrum of heritage values; significant evolution can be mapped by looking at changing value types embedded in the 1964 Venice Charter () through the Burra Charter (1979 and subsequent), the Nara Document (and subsequent regional reports), and Nara + 20 (). Burra placed a situational notion of “cultural significance” at the center of policy and valorized grassroots contributions to decision making; Nara confirmed a relativist and dynamic notion of authenticity and empowered cultures outside of the Western tradition to assert their own notions. Note by contrast the persistence of hegemonic, literally universalizing claims about value (for example UNESCO’s “outstanding universal value”).

This watershed shift to include societal values was instigated by forces outside the field—though of course it was championed by many working in the field. Though conservation professionals often adopt progressive, inclusive cultural politics, there remains some inertia to change in the expert norms, public policies, institutions, and mutual expectations of professionals and citizens. Meanwhile, the turn toward societal values has been widely felt in reshaping theory, on-the-ground practices, and the balance of power among institutions, professionals, and communities and clients.

The Turn toward Societal Values

The values turn strengthened the field’s traditional responsibility for the curatorial care of buildings and sites, and joined it with a responsibility to respond more deeply to the multitude of communities valorizing these places. The expanding roles played by conservation professionals—beyond technical expertise into mediation, facilitation, and embracing stakeholder status—are now widely acknowledged in practice (, 34).

Embracing the values turn requires a greater focus on underlying and uncertain processes of valorization, decision making, and gauging the social impact of conservation, as distinct from the traditional emphasis on the certainties of the materiality and originality of buildings and sites themselves as the main index of conservation’s success. This shift in purpose and objectives (again, it is a shift, not a wholesale replacement) provokes rethinking of concepts, methods, and the roles of experts and institutions in conservation. As the conservation field embraces the complexities of a values-rich social practice—in addition to the challenges of curatorship, scholarship, and materials science—new lines of research and innovation emerge as priorities.

Even if traditional conservation practitioners of the pre- and postwar eras—especially the leading figures—understood all the social complexities of conservation (as well as the design, interpretation, and scientific challenges), they did not have the range of expertise or institutions to deal robustly with all of them. This instigated various dissatisfactions or critiques of the limits of the curatorial paradigm. This is evident for example in the published work of James Marston Fitch: he realized the economic and social dynamism affecting historic preservation in the 1960s and 1970s, and elaborated on the need for a broader response to a broader set of values, yet still responded to projects in a fundamentally curatorial mode.

How has the turn toward societal values manifested in heritage conservation theory and practice in the last generation? The topics on the suggestive list below are already being explored in the realms of practice, policy, and theory, and they were among the topics animating the GCI research on values and heritage reaching back to the 1990s.7

Deeper understanding of values as ascribed to heritage places by people, as opposed to being inherent in the materiality of places. This flows from the broader intellectual transformations of poststructuralism and postmodernism, questioning objectivity and highlighting the power exercised by experts and top-down decision makers to frame values.

Alternative forms of built heritage. Cultural landscapes, intangible heritage, and reconstructions (actual and virtual) have grown more prominent. Each in its own way communicates something about the value of a cultural form or process without relying on traditional means of representing values only in material forms.

Broader notions of “ownership.” The political and ethical prominence of stakeholders involved in heritage decision processes have, in effect, created new forms of ownership related to heritage places. Some stakeholders are able to assert strong control over a site without owning it legally.

Greater recognition of Indigenous and subaltern peoples. Postcolonial critiques have revealed Western normative influences and internationalizing narratives and politics affecting conservation. The distinctions between World Heritage Convention and Nara conceptions of value and authenticity, for instance, are by now well known, and scholars and practitioners continue to explore ways of breaking with monolithic Western understandings of heritage and conservation as European creations ().

Economic valuation. The values turn also opened the heritage conservation field to the challenges and opportunities of economic values (; ). The emergence of economic valuation as an area of conservation practice, research, and policy is based on a realization that heritage has “economic lives,” and that important societal values are expressed through markets for heritage goods and experiences. The introduction of economic concepts and methods recalibrates the values ascribed to a place, tending to privilege societal over heritage values.

New institutional forms. Public-private partnerships, interest groups, trusts, and other hybrid organizations have long played important roles in the conservation field alongside state agencies. Highly participatory and transparent decision making processes, privatization, and changing attitudes toward central governments make institutional arrangements an area in need of deeper study.

Status of the conservation profession. The consolidation and codification of heritage conservation as a profession continues to evolve in relation to other, allied professional realms working in history, anthropology, design, and museums. The status of the conservation profession—represented by ICCROM, ICOMOS, UNESCO, graduate university departments, et cetera—is continually challenged by external forces reshaping the markets for conservation expertise as well as by internal differences of opinion on how to define the field.

The Onset of “Critical Heritage Studies”

The politicization of heritage cuts different ways. In a progressive direction, heritage is ever more closely linked with identity politics, empowering citizens and nonexperts and embedding participation into societal expectations as well as professional practices. In a neoliberal direction, markets and private institutions have acquired more power; econometric valuation and business logic gain influence in decisions about conservation and its management, resulting in clear trends toward privatization and threats to public good. Politicization has foregrounded arenas of conflict—for instance the issue of gentrification, or recognition of negative or traumatic heritage—as well as made space for a broader range of voices, identities, and narratives.

Following the turn toward societal values, and the pragmatic responses outlined in previous sections, intellectual discourse around “critical heritage studies” has emerged as a radical, thoroughly politicized response to the conservation profession’s slow process of response and reform.8 At turns dismissive and constructive, critical heritage studies discourse tends to amplify the issues raised by values-centered conservation and explore the myriad conflicts encountered in practice. At its best, this discourse points toward new forms of reflective conservation practice. At its worst, it tends toward solipsistic critiques of heritage cultures while raising existential questions about conservation as a profession. The political and pragmatic challenges of conservation outlined in this chapter deserve serious exploration, and the cadre of scholars identifying with “critical heritage studies” contribute to this.

In light of changes in the conservation field and the scholars who study it (who seem less committed to practice), how are critical heritage studies contributing to the work of conservation?9

- Laurajane Smith’s concept of “authorized heritage discourse” (, 4) highlights top-down, normative conceptions of heritage more or less imposed by national bodies, or by experts. This feeds the notion that more local expressions of heritage value are more politically authentic.

- Tensions between expert and nonexpert perspectives are manifest in the different values, interests, and identities expressed in heritage identification and decision-making processes. Conflict resolution has gained recognition as a typical role of conservation professionals (alongside established roles as facilitators, brokers, agents, historians, scientists, and designers) ().

- East-versus-West formulations of cultural difference have been the subject of scholarship for more than a generation. Earlier works positing Asian cultures as fundamentally different or fundamentally similar in terms of constructing heritage have given way to more nuanced recent work on cultural fusion, positing a model of many different Indigenous modernities (; ; ; ).

- Values-centered conservation aims at understanding and strengthening the relationships between stakeholders and sites, people and places. Critiques of values-centered conservation can present a false choice between conservation relating to materials, buildings, or sites themselves or to communities, stakeholders, and people ().

- The assertion of access to heritage as a human right has emerged as a minor but profound argument, gaining new prominence in light of purposeful war-zone destruction of heritage places and refugee crises (; ).

- Heritage conservation has been reframed as part of other fields’ projects. Landscape urbanism’s ecological drivers and aestheticization of redundant industrial sites is one example of “mission creep” in allied professional fields verging toward significant overlap with professional conservation. In one sense, this trend can seem akin to one field colonizing the expertise of another (). In another sense, the interweaving of heritage conservation concepts and goals with other fields can be posed as a model partnership for elevating the prominence of heritage issues, as with UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape initiative ().

- Calls for increased accountability and transparency in the form of measurement and evaluation have proliferated in the last generation in all areas of public policy. Expressing conservation’s functions in terms of measurable outcomes (social, environmental, economic) is an important area of applied research. Likewise, communicating the effects and results of consultative processes rivals the need to evaluate conservation policies econometrically.

Tradition dies hard. Materiality, artistic and historic values, nationalistic norms of heritage construction, and the objective status of heritage and conservation experts all have great staying power as traditions within the field. The turn toward societal values reinforced these canons while challenging conservation to also reckon with bigger questions like political legitimacy, identity politics and cultural diversity, economic performance and governance under neoliberal regimes, environmental degradation and resilience, and more. Critique, evolution and innovation—in response to transformative changes in global, national, and local societies—are the concerns of the field’s next generation and are taken up in the balance of the chapter.

Current Issues

The previous sections examined the historical and political forces that shaped the heritage field in the past half century and influenced the turn toward societal values. This shift poses significant questions for contemporary conservation practice and policy. It also illuminates substantial differences in how heritage is rationalized as a matter of public policy and investment. This section examines these differences and the challenges they pose with an eye toward exploring how values-based methodologies can more effectively serve the evolution of the field and the well-being of society.

Essential versus Instrumental Views of Heritage

As noted earlier in this chapter, the distinctions between heritage values and societal values are underpinned respectively by concepts framed by Gamini Wijesuriya, Jane Thompson, and Christopher Young in their UNESCO manual Managing Cultural World Heritage (), which we frame as essential and instrumental:

The first approach rests on the assumption that cultural heritage and the ability to understand the past through its material remains, as attributes of cultural diversity, play a fundamental role in fostering strong communities, supporting the physical and spiritual well-being of individuals and promoting mutual understanding and peace. According to this perspective, protecting and promoting cultural heritage would be, in terms of its contribution to society, a legitimate goal per se.

The second approach stems from the realization that the heritage sector, as an important player within the broader social arena and as an element of a larger system of mutually interdependent components, should accept its share of responsibility with respect to the global challenge of sustainability.

The essential perspective dominates in heritage practice and policy; it reinforces heritage “as an end in itself … that should be protected and transmitted to future generations” (, 20). While the values turn (discussed above) is reflected in more participatory conservation practices that engage more diverse stakeholders, the emphasis is often on translating the broader range of societal values that multiple publics ascribe to places into a set of heritage values that can be preserved through professional protection, planning and management, and intervention. This reductionist process through which heritage experts cull relevant societal values and incorporate them into decision making is self-reinforcing; it ultimately supports the essential goal of preserving the fabric of place.

This essential approach is codified in policy, because the criteria used to list heritage are still largely driven by curatorial precepts (see fig. 5.2 in Kate Clark’s contribution to this volume). As conservation professionals, we recognize that heritage is a politicized social construction, as demonstrated by the inclusion of “social value” writ large in heritage management in many contexts, including Australia and the United Kingdom. However, even social value is framed within a strategic aim of saving the physical heritage resource, albeit in relation to social contexts and uses. As Gustavo Araoz contends, “If we analyze what has guided the conservation endeavor, it becomes clear that heritage professionals have never really protected or preserved values; the task has always been protecting and preserving the material vessels where values have been determined to reside” (, 58–59).

In light of contemporary societal and environmental conditions, the values turn compels a concomitant exploration of heritage beyond its essential core and material focus so as to demonstrate its instrumentality in the broader churn of contemporary life.

Limitations of a Heritage Values or Essential Approach

Heritage is a social construct; it is created by people ascribing value to places (; ; ). Increased democratization, freedom of expression, and social media and other communications contribute to the proliferation of new forms and platforms for heritage that emerge from wide-ranging communities, narratives, and memories. From the destruction of residential schools for First Nations children in Canada, to the 3D replication of decimated monuments as public art installations, to the role of cultural heritage in transitional justice and reconciliation in South Africa, the built environment is a medium for new kinds of public discourse, and this influences how heritage is defined and treated materially (or not).

These developments illustrate some of the ways in which heritage serves multiple societal aims, and they likewise confront limitations of heritage-value-driven policy and practice. Understanding the limitations and the opportunities they present for conservation decision making can elucidate the dynamic between heritage values and societal values, thereby informing the improvement of policy tools, professional practice, and educational approaches.

Differing geocultural attitudes and norms make for more diverse interpretations of what constitutes heritage and how conservation is approached. The largely Western (European) foundation of globalized heritage policy (Laurajane Smith’s “authorized heritage discourse”) often leads to a false dichotomy of “Western” versus “non-Western” approaches to heritage, when in fact differences can be characterized in myriad ways (localized/internationalized, urban/rural, expert/nonexpert, modern/traditional, colonial/Indigenous, et cetera). Likewise, such differences are not necessarily dichotomized opposites, but rather represent reductionist ways of communicating a range of perspectives. However, by bookending the concepts as seeming polarities, the field can create separations in professional practice that may not exist, or at least not in the same way, within different sociocultural realities. Discrete projects and policy documents like the Burra Charter work to transcend these divides and more fully recognize the multiplicity of values, but the integration of such approaches into public policy beyond a few countries has been more challenging.

Such reductionism is evident in typologizing heritage as well. By categorizing heritage as tangible versus intangible, movable versus immovable, archaeological sites, historic centers, cultural landscapes, et cetera, the heritage field creates a functional vocabulary for cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural communication and collaboration. At the same time, these typologies run the risk of perpetuating the dominant cultures, theories, and approaches through which such typologies are developed, and again can lead to the exclusion of different views and approaches.

Further, heritage values are often categorized through reductionist typologies (aesthetic, historic, environmental, economic, associative) as a practical means of understanding the significance of a place and guiding professional decision making. But such typologies can nonetheless exclude those who perceive their past, their identity, and notions of “heritage” in different ways, because such categorizations are also forms of control (). The disciplinary tools and languages through which heritage values are assessed can also minimize complexity and thus limit inclusion. Whether through economic valuation or curatorial histories, such methods can sometimes discount different kinds of knowledge and ways of knowing.

Exclusion can be intergenerational as well. The act of designation or listing, under many if not most government laws, confers indefinite recognition, and in many cases protection in perpetuity. However, heritage research over the last quarter century demonstrates that values can change over time (; ; ; ; ; ). Stakeholders of the future may not value a place in the same way, or at all. The narratives created through heritage values may not resonate with subsequent generations (), nor may the living conditions afforded by historic environments meet their needs. Acknowledging that delisting of sites occurs infrequently, the dominant policies in the field incur an ever-growing accumulation of heritage that bequeaths not only those places but the burden of their stewardship to the generations to come (; ). Thus, the temporality of heritage values raises questions of intergenerational equity and how heritage conservation can more effectively anticipate and accommodate change over time ().

These concerns of temporality, relativism, categorization, exclusion, intergenerational equity, sustainability, and more do not negate the importance of heritage values. Rather, understanding their relationship to broader societal values can help unmask biases and enable more instrumental approaches to heritage.

Societal Values and the Instrumentality of Heritage

The conservation profession differentiates certain structures, sites, and landscapes from the rest of the built environment because of their heritage values. This concept has been codified in public policy through processes of designation or listing. Identifying places of heritage value seeks not only to raise awareness about them, but also to protect them from political and/or market forces of destruction, thereby endowing them with a certain right to survival over other elements of the built environment. Additional policy tools augment these protection efforts, usually through some form of knowledge transfer or technical assistance, regulation, allocations of property rights, incentives, or government stewardship or ownership (). As the values turn sheds light on the sometimes-unintended consequences of heritage decision making, the conservation field is held increasingly accountable for its outcomes as a form of public policy. Quantifying and qualifying its benefits to society, beyond traditional heritage values, is ever more important as public needs and interests compete for limited resources. The “cultural heritage as a legitimate end in itself” argument, when not substantiated by evidence of its contributions to the environment, the economy, and society, marginalizes the field and limits its leverage for attracting investment (, 21).

This accountability to demonstrate the instrumentality of heritage conservation is made more challenging by social, demographic, and environmental changes, and the literally global scope of many contemporary issues:

- Energy and resource consumption. Existing buildings account for large percentages of global energy, water, and natural resource consumption, as well as greenhouse gas emissions, compelling changes in how we manage the built environment.

- Climate change and resulting sea-level rise. Projected sea-level rise may force geographic shifts away from coasts, requiring major transformations in infrastructure and buildings.

- Population growth and urban shifts. Urban population growth puts tremendous pressure on the built environment, and land consumption in urban areas is expanding at twice the rate of their populations ().

- Forced displacement. The UN Refugee Agency reported more than sixty-eight million people displaced in 2017 due to conflict and persecution. Numbers are projected to grow significantly as a result of climate refugees, meaning greater mobility and diaspora.

- Immigration and plurality. Many cities, especially in North America and Europe, are home to increasing foreign-born populations. Mobility and migration are contributing to more plural citizenries, and thus more diverse values and narratives ascribed to the built environment.

Conservation cannot address all of these challenges, but these empirical realities will influence societal values and priorities, thereby affecting heritage policies. Expanding from a heritage values focus to a societal values focus is not simply mission creep for conservation; it is a responsible evolution of the field and a recognition of the political interdependence of people and heritage places. How heritage is valued and who values it will fundamentally shift with evolving built environments, communities, and cultures.

The Potential for Change

This analysis suggests that the conservation field must move beyond the physical protection of heritage to exercise its broader benefits. Heritage conservation is now a widely accepted form of public policy; it is dependent on government support and administration in nearly all countries, illustrated by the fact that 193 States Parties have ratified the World Heritage Convention. This implies an affirmative obligation on the part of conservation to serve the public interest writ large.

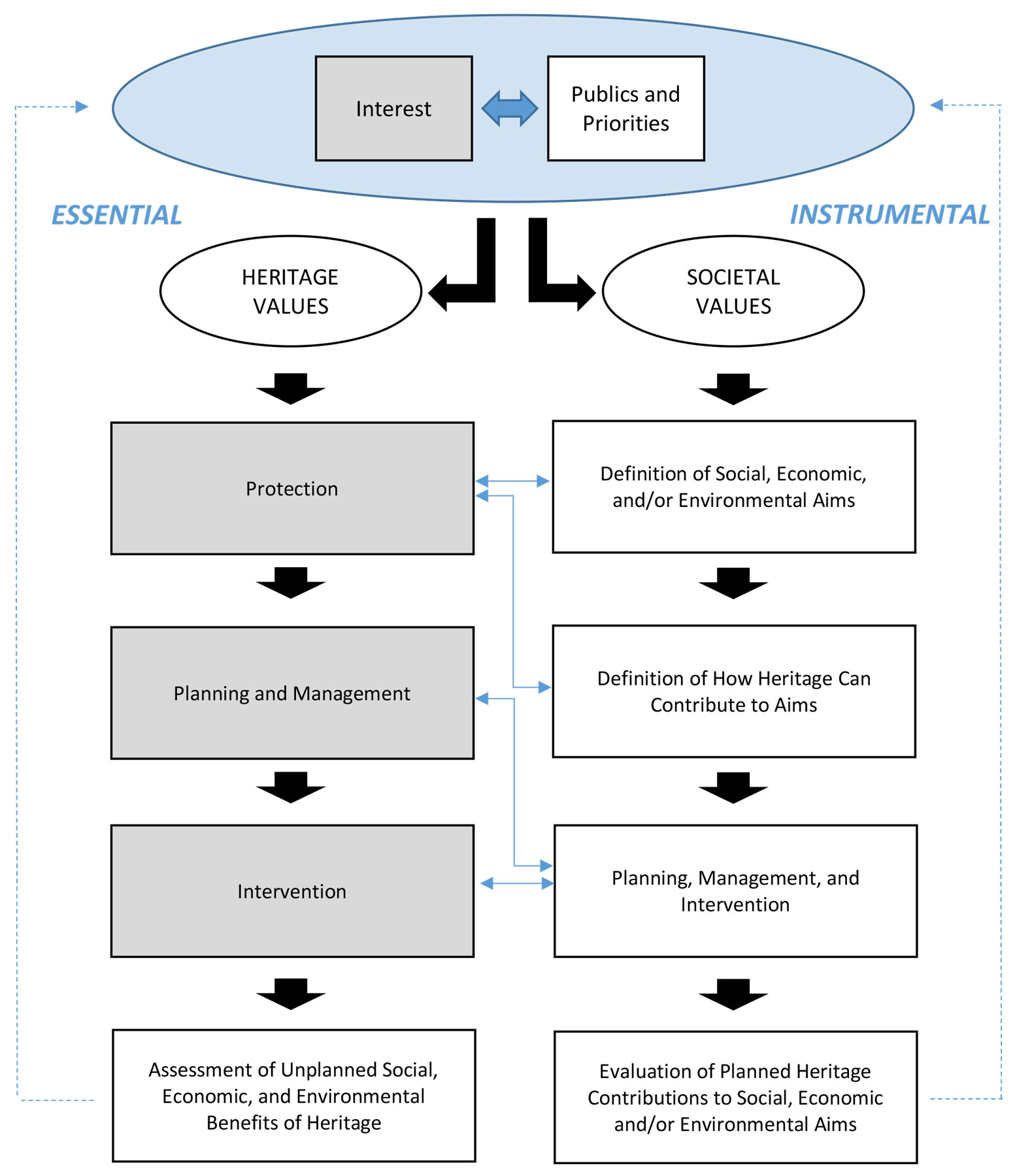

The diagram in figure 2.3 seeks to demonstrate the relationship of the essential versus instrumental approach, and how heritage values and societal values respectively reorient decision-making structures. It builds on the model developed in the earlier GCI research report Values and Heritage Conservation (, 4–5), the core elements of which are indicated by the shaded gray boxes. It frames the concept of heritage, represented by the blue oval, as something constructed and mediated by the interests of varying publics and their respective priorities, and demonstrates the different outcomes achieved by essential and instrumental paths.

Figure 2.3

Figure 2.3An important assertion illustrated in this diagram is that an essential approach to heritage—one that focuses on the strategic aim of physically conserving a place—will not ipso facto demonstrate the instrumentality of heritage. When preservation institutions and professionals are prompted to articulate the positive societal outcomes of conservation, the responses run the gamut: preserving cultural diversity, enhancing civil society, fostering pluralistic discourse, promoting social inclusion and tolerance, creating a more environmentally sustainable built environment, generating economic benefits, promoting good urbanism, et cetera. But what is the mechanism? The hypotheses of cause and effect? The logic model? We cannot designate historic places because of their heritage values, then expect to achieve societal aims and reinforce societal values as a by-product of physical conservation. Such benefits can only be effectively achieved if they are a direct and explicit aim of heritage policy and practice.

Changing Governance and Policy

An instrumental approach to heritage that is unequivocally driven by societal values poses and confronts many challenges in policy and governance structures. Many of the laws, policies, and professional doctrines that constitute the institutional “infrastructure” of heritage have not been widely updated to reflect a progression in thinking about values or adapt to the politicization of heritage. In some cases, the introduction of new tools for understanding values—from ethnographic methods to consensus-building techniques—is hindered by institutional and regulatory frameworks that are not flexible enough to accommodate significant change. Innovation is certainly evident in the shifting responsibilities across public and private sectors and institutions, and demonstrates creative approaches to such institutional rigidity. Increased privatization, the rise of public-private partnerships, and the hybridization of NGOs illustrate the ways in which these traditional infrastructures are shifting in neoliberal economies to divest governments of increasing financial burdens. But markets do not have the ability to ensure intra- and intergenerational equity (). The discursive and regulatory functions needed to promote social justice are the bailiwick of governments (). As Graham Fairclough notes, “It is quite difficult … in the heritage sphere, to see social participation as an alternative to government action, instead of being an addition to it … because the one guarantees the validity and efficacy of the other” (, 245).

In this context of governance, shifts in conservation decision making from the more curatorial, expert-driven heritage values to those that more directly engage societal values engender greater stakeholder participation. But institutions may have limited legal mandate, resources (human and financial), and expertise to undertake meaningful consultation. Do heritage institutions and government agencies have the disciplinary and professional breadth and depth to expand their mission in these ways? Even more challenging, such engagement may lead to very different perspectives on whether and how to preserve a place. Can existing regulations and institutional polices support and enable such diversity and inclusion in decision making? Can an enhanced understanding of societal values help to evolve institutional policies and practices toward instrumental approaches?

Among the principal tools in institutional heritage decision making are statements of significance. Many of these may be expert driven, while others may incorporate the input of a variety of stakeholders. As noted previously, these statements are essentially technical outputs; they do not in and of themselves compel participatory discourse, nor does the lack of such discourse necessarily reduce their validity in many institutional contexts. In theory, such statements may be updated and revised with changing conditions, such as the development of a new management plan or expansion of a protection zone. In practice, this can pose institutional challenges. In the city of New York, for example, the Landmarks Preservation Commission develops designation reports that assess significance to support its decision making about what properties to preserve. Once a property is landmarked, that report is a legal and binding document; it cannot be changed, not even if only to correct the date of a building. The authority of experts in ascribing value has been openly challenged, as in a recent legal case in Chicago decrying the subjectivity of preservation criteria and decisions.10 While there may be greater flexibility in other geographic and institutional contexts, this raises important questions about whether public heritage agencies are equipped to move beyond decision making derived from expert heritage values toward more participatory processes that are directly responsive to societal values, which effectively require more dynamic models of governance and management.

It likewise raises issues about how and when institutions invest in such participatory discourse. Institutional focus in many contexts may be largely weighted toward identifying and designating new heritage places. The growth of heritage lists suggests that this front-end investment in continually expanding heritage rosters can stretch public resources for long-term heritage management and post-designation assessments (). This may limit the potential for participation to recur over time.

Changing Education and the Profession

At a professional level, engaging more robustly with societal values raises similar issues regarding stakeholder participation and interdisciplinary engagement. Are heritage practitioners equipped to adapt and implement the tools of anthropology, ethnography, economics, conflict resolution, and more, and/or to work in concert with these allied disciplines? Fundamentally, collective action in heritage management requires some degree of consensus building, but relationships, and forms and levels of consultation, influence roles and outcomes. Should heritage practitioners, allied professionals, and community members share decision-making power? Are heritage professionals serving as experts with higher authority, facilitators of community decision making, or both?

The professional toolbox for heritage decision making that addresses broader societal values (engaging stakeholders; delineating, mapping, and articulating values; integrating values in assessments and long-term management) remains somewhat limited. While research and practices in allied fields can certainly be applied to heritage conservation, they require informed adaptation. This means not only that those from other disciplines must engage more with heritage, but also that those in heritage may step beyond traditional boundaries to help forge connections and focus methodological development (a key point regarding this research). Bringing knowledge of ethnography, environmental management, consensus building, and more, as well as “local” forms of knowledge and knowing, to bear on heritage conservation can lead to new innovations in values-based approaches, but will require concerted effort across institutional, professional, and educational actors.

Academic institutions and practitioners play a critical role. A more inclusive understanding of heritage and values recognizes different kinds of knowledge and different ways of knowing, but formal education at the university level tends to emphasize material conservation and historical and architectural value. The practical skills needed to advocate for listing, preserve structures, and manage heritage predominate in many parts of the world; the political, discursive, analytical, and creative skills needed to instrumentalize heritage as a societal contributor play a lesser role. While a values discourse is certainly emerging in many heritage programs, the extent to which students are being trained to engage with stakeholders and undertake community assessments remains unclear.

The role of the academy in research is also at an important juncture. Certainly scholarship in the area of “critical heritage discourse” has shed new light on issues of cultural dominance and social justice in relation to conservation. But research has struggled to move beyond critique to inform policy and practice.

Changing Conservation Aims and Metrics

The above challenges raise important issues about balancing the heritage field’s focus on the past with an accountability to the future as it demonstrates instrumentality and responds to societal values. Barriers to addressing this include lack of consensus regarding the primary aims of heritage conservation vis-à-vis society (beyond conservation as an end in itself) and lack of metrics to assess how those aims are being met through the use of heritage. On the former point, consensus will likely never be achieved because societal values will be different in each community or geopolitical context, thereby influencing aims and how heritage can contribute. However, a more robust toolbox for the latter could address the diversity of aims and approaches by applying different metrics in varying combinations and contexts.

Important, but limited, progress has been made in the realm of heritage metrics, such as Historic England’s Heritage Counts, which uses socioeconomic indicators. In the United States, studies by the National Trust Preservation Green Lab (now Research and Policy Lab) measure vitality in older neighborhoods as well as the avoided environmental impacts of reusing existing buildings. Parks Canada’s commemorative integrity process assesses the communication of values to visitors. These initiatives demonstrate the breadth of societal aims against which heritage success is being measured.

A critical point, nonetheless, is that many of these innovative efforts are still largely driven by an essential model, in that they seek to substantiate traditional conservation practices and policies by quantifying unplanned benefits. While they certainly work toward demonstrating instrumentality, they do so without internalizing societal values in the heritage decision-making process. In many cases, they effectively co-opt economic and environmental aims and metrics to rationalize conservation and rely heavily on its physical legacy as an indicator of success. The proliferation of economic impact studies, for example, seeks to justify public investment in heritage conservation based on economic measures. More recent environmental studies that quantify the avoided impacts of preserving existing buildings and the population density of historic districts likewise rationalize conservation in terms of environmental indicators. But current decision making about heritage, at least about what should be preserved, is not based on economic or environmental values alone.

Approaches that engage a broader range of societal values may help to more clearly elucidate and rationalize these fundamentally social functions and benefits of participatory heritage decision making, so that the heritage field does not rely predominantly on its physical legacy as an indicator of success, or too heavily on the metrics of other fields. The heritage field has yet to articulate clear aims and associated metrics with relation to inclusion, diversity, tolerance, intergenerational equity, economic profit seeking, ideology-driven protection or iconoclasm, responses to trauma or disaster, or other societal values that are arguably more central to decision making at all scales and contexts.

By redefining the social dimension of heritage beyond static statements of significance and toward dynamic processes of engagement with clear societal aims, the heritage field has the potential to serve as a powerful agent of change. A primary aim of this GCI project is exploring alternative scenarios for practice that can lead to the development of methods and approaches that can support societal-values-driven heritage policy and action.

Conclusions

This attempt to learn from the past, evaluate present conditions, and anticipate future concerns mirrors the modus operandi of the heritage enterprise. Through iterative evaluations of values-based methods (applying both heritage-intrinsic and societal-instrumental perspectives), the field can create a wider spectrum of conservation alternatives and future heritage scenarios, rather than strategically planning and managing places to protect heritage values alone. This is an important point of reckoning.

The long time frame inherent in the idea of conservation, and contemporary acknowledgement of growing cultural diversity (and fragmentation, and fusion), make the societal-values issues more vexing. Practically, this review of trends, concepts, and problems is meant to embed better learning, self-critique, evaluation, and training functions within the professional field of conservation, and inspire practices of sustainable conservation in all senses of the word (from materiality to social meaning to environmental impact to financing).

Extending this analysis to emergent issues on the horizon proactively engages the societal and environmental changes with which the heritage field will soon contend. Heritage values alone will not suffice; the field must be cognizant of and responsive to the shift in societal values toward resilient and inclusive approaches to managing the built environment. How can the heritage field instrumentally address social, economic, and environmental concerns so that conservation serves humanity and the planet by redefining its goals in relation to societal values, not just to heritage values? We posit that a primary challenge of contemporary conservation theory and practice is to weave together both perspectives more robustly.

Notes

- Values as qualities departs from another common usage of the word in English: values as ethics, philosophies, or normative codes of behavior. ↩

- As David Myers, coeditor of this volume, related to the authors, many conflict-resolution professionals (among others) use “values” in the sense of ethics, and frame conflicts in terms of interests, identities, and values. Such a framework (as elaborated by ) presents a substantially different perspective from that employed in the present paper—in which “values” are stipulated as the a priori object of analysis. ↩

- Essential and instrumental align with the “intrinsic” and “instrumental” approaches to heritage described by UNESCO in Wijesuriya, Thompson, and Young (). We have refrained from the use of “intrinsic” to avoid confusion with the debate over intrinsic versus ascribed values in relation to heritage. ↩

- The notion of “curatorial” conservation is also developed in the work of James Marston Fitch () and Harold Kalman (, 49); the excellent social histories of conservation in Europe by Françoise Choay () and Miles Glendinning () also elaborate on the concept. ↩

- Alois Riegl () established this distinction; see Choay () and Glendinning () for broader historical overviews of changing types of “monuments,” or more broadly, the changing objects of conservation attention. ↩

- For instance, some alternative means of generating statements of significance have arisen using participatory methods to include substantially the views of nonexperts. (Note that “nonexpert” refers to those outside the heritage professions; it does not presume that those outside the field or within the community have no expertise.) Examples include the recent work of Chris Johnston in Australia (collected at http://www.contextpl.com.au/category/papers-and-articles/); the (US) Orton Foundation’s Heart & Soul methodology (described at https://www.orton.org/build-your-community/community-heart-soul/); public design methods, including the work of landscape architect Randolph T. Hester (); and the community arts group Common Ground (sourced at https://www.commonground.org.uk/). ↩

- Years of GCI’s work in this area is available under the Research on the Values of Heritage project: http://www.getty.edu/conservation/our_projects/field_projects/values/. ↩

- “Critical” remains in quotes due to its polemical and sometimes misleading use: “critical heritage studies” implies that any preexisting studies of heritage lacked critical perspective, which is a categorical overinterpretation. There remains a significant divide between studies grounded in conservation practice (not just empirical observation of such) and studies undertaken as purely scholarly projects. ↩

- See Logan, Nic Craith, and Kockel () or programs for Association of Critical Heritage Studies conferences at http://www.criticalheritagestudies.org/. ↩

- See 2013 IL App (1st) 121701-U, http://illinoiscourts.gov/R23_Orders/AppellateCourt/2013/1stDistrict/1121701_R23.pdf. ↩

References

- Abbas, Ackbar. 1997. Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Abramsohn, Jennifer. 2009. “Dresden Loses UNESCO World Heritage Status.” Deutsche Welle, June 25, 2009, http://www.dw.com/en/dresden-loses-unesco-world-heritage-status/a-4415238.

- Araoz, Gustavo F. 2011. “Preserving Heritage Places Under a New Paradigm.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 1 (1): 55–60.

- Ashworth, Gregory J. 1994. “From History to Heritage—From Heritage to Identity.” In Building a New Heritage: Tourism, Culture and Identity in the New Europe, edited by Gregory John Ashworth and Peter J. Larkham, 13–30. London: Routledge.

- Australia ICOMOS. 2013. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. Burwood: Australia ICOMOS. http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf.

- Avrami, Erica C., Randall Mason, and Marta de la Torre. 2000. Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/values_heritage_research_report.

- Bandarin, Francesco, and Ron van Oers. 2012. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Benhamou, Francoise. 1996. “Is Increased Public Spending for the Preservation of Historic Monuments Inevitable? The French Case.” Journal of Cultural Economics 20 (2): 115–31.

- Blinder, Alan. 2017. “Tributes to the Confederacy: History, or a Racial Reminder in New Orleans?” New York Times, May 12, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/12/us/tributes-to-the-confederacy-history-or-a-racial-reminder-in-new-orleans.html.

- Choay, Françoise. 2001. The Invention of the Historic Monument. Translated by Lauren M. O’Connell. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Coughlan, Sean. 2016. “Oxford Rhodes Statue Row Is Part of Global Protest.” BBC News, January 26, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/education-35441074.

- Council of Europe. 2005. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society: Faro, 27. X.2005. Council of Europe Treaty Series 199. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe. Accessed July 31, 2018. https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680083746.

- de Monchaux, John, and J. Mark Schuster. 1997. “Five Things to Do.” In Preserving the Built Heritage: Tools for Implementation, edited by J. Mark Schuster, John de Monchaux, and Charles A. Riley II, 3–11. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

- Denslagen, Wim. 1993. “Restoration Theories, East and West.” Transactions of the Association for Studies in the Conservation of Historic Buildings 18:3–7.

- Etlin, Richard A. 1996. In Defense of Humanism: Value in the Arts and Letters. Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Fairclough, Graham. 2014. “What Was Wrong with Dufton? Reflections on Counter-Mapping: Self, Alterity and Community.” In Who Needs Experts? Counter-Mapping Cultural Heritage, edited by John Schofield, 241–48. Heritage, Culture and Identity. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Fitch, James Marston. 1982. Historic Preservation: Curatorial Management of the Built World. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Glendinning, Miles. 2013. The Conservation Movement: A History of Architectural Preservation: Antiquity to Modernity. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Greffe, Xavier. 2004. “Is Heritage an Asset or a Liability?” Journal of Cultural Heritage 5 (3): 301–9.

- [Heritage and Society]. 2015. “Nara + 20: On Heritage Practices, Cultural Values, and the Concept of Authenticity.” Heritage and Society 8 (2): 144–47.

- Hester, Randolph T. 2006. Design for Ecological Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Holtorf, Cornelius, and Anders Högberg. 2014. “Communicating with Future Generations: What Are the Benefits of Preserving Cultural Heritage? Nuclear Power and Beyond.” European Journal of Post-Classical Archaeologies 4:343–58. http://www.postclassical.it/PCA_vol.4_files/PCA%204_Holtorf-Hogberg-1.pdf.

- Hosagrahar, Jyoti. 2005. Indigenous Modernities: Negotiating Architecture and Urbanism. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Hutter, Michael, and David Throsby, eds. 2008. Beyond Price: Value in Culture, Economics, and the Arts. Murphy Institute Studies in Political Economy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ICOMOS. 1931. The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments–1931. [Paris]: ICOMOS. http://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments.

- ICOMOS. 1965. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter 1964). [Paris]: ICOMOS. https://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf.

- ICOMOS. 1994. The Nara Document on Authenticity. Paris: ICOMOS. https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf.

- Johanson, Mark. 2013. “Dresden Bridge That Got City Booted Off World Heritage List Opens.” International Business Times, August 26, 2013, http://www.ibtimes.com/dresden-bridge-got-city-booted-unesco-world-heritage-list-opens-1398351.

- Johnston, Chris. 1992. What Is Social Value? A Discussion Paper. Australian Heritage Commission Technical Publications Series 3. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. http://www.contextpl.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/What_is_Social_Value_web.pdf.

- Kalman, Harold. 2014. Heritage Planning: Principles and Process. New York: Routledge.

- Kaufman, Sanda, Michael Elliott, and Deborah Shmueli. 2003. “Frames, Framing and Reframing.” In Beyond Intractability. Edited by Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Boulder: Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado. http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/framing.

- Lake, Robert. 2002. “Bring Back Big Government.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26 (4): 815–22.

- Lipe, William D. 1984. “Value and Meaning in Cultural Resources.” In Approaches to the Archaeological Heritage: A Comparative Study of World Cultural Resources Management Systems, edited by Henry Cleere, 1–11. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Logan, William, Máiréad Nic Craith, and Ullrich Kockel, eds. 2016. A Companion to Heritage Studies. Blackwell Companions to Anthropology 28. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons.

- Lowenthal, David. 1985. The Past Is a Foreign Country. Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mason, Randall, ed. 1999. Economics and Heritage Conservation: A Meeting Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute, December 1998, Getty Center, Los Angeles. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Mason, Randall. 2008. “Be Interested and Beware: Joining Economic Valuation and Heritage Conservation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 14 (4): 303–18.

- Muñoz Viñas, Salvador. 2005. Contemporary Theory of Conservation. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Myers, David, Stacie Nicole Smith, and Gail Ostergren, eds. 2016. Consensus Building, Negotiation, and Conflict Resolution for Heritage Place Management. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/consensus_building.html.

- Nordhaus, William D. 1992. “The Ecology of Markets.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 89:843–50.

- Poulios, Ioannis. 2010. “Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 12 (2): 170–85.

- Riegl, Alois. [1903] 1982. “The Modern Cult of Monuments.” Translated by Kurt W. Forster and Diane Ghirardo. Oppositions 25:21–51.

- Ryckmans, Pierre. 1989. “The Chinese Attitude towards the Past.” Papers on Far Eastern History 39:1–16.

- Schoch, Douglas. 2014. “Whose World Heritage? Dresden’s Waldschlösschen Bridge and UNESCO’s Delisting of the Dresden Elbe Valley.” International Journal of Cultural Property 21 (2): 199–223.

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Seto, Karen C., Burak Güneralpa, and Lucy R. Hutyrac. 2012. “Global Forecasts of Urban Expansion to 2030 and Direct Impacts on Biodiversity and Carbon Pools.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (40): 16083–88.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Tainter, Joseph A., and G. John Lucas. 1983. “Epistemology of the Significance Concept.” American Antiquity 18 (4): 707–19.

- Waldheim, Charles. 2016. Landscape as Urbanism: A General Theory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Walter, Nigel. 2014. “From Values to Narrative: A New Foundation for the Conservation of Historic Buildings.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (6): 634–50.

- Wijesuriya, Gamini, Jane Thompson, and Christopher Young. 2013. Managing Cultural World Heritage. World Heritage Resource Manual. Paris: UNESCO. http://whc.unesco.org/en/managing-cultural-world-heritage/.

- Winter, Tim. 2013. “Clarifying the Critical in Critical Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19 (6): 532–45.